McManus: The candidates play gotcha

There’s no argument about one thing this election year: The biggest issue on Americans’ minds is the economy and which presidential candidate could better help it grow. So why does what should be a serious policy debate sound so much like a schoolyard spat?

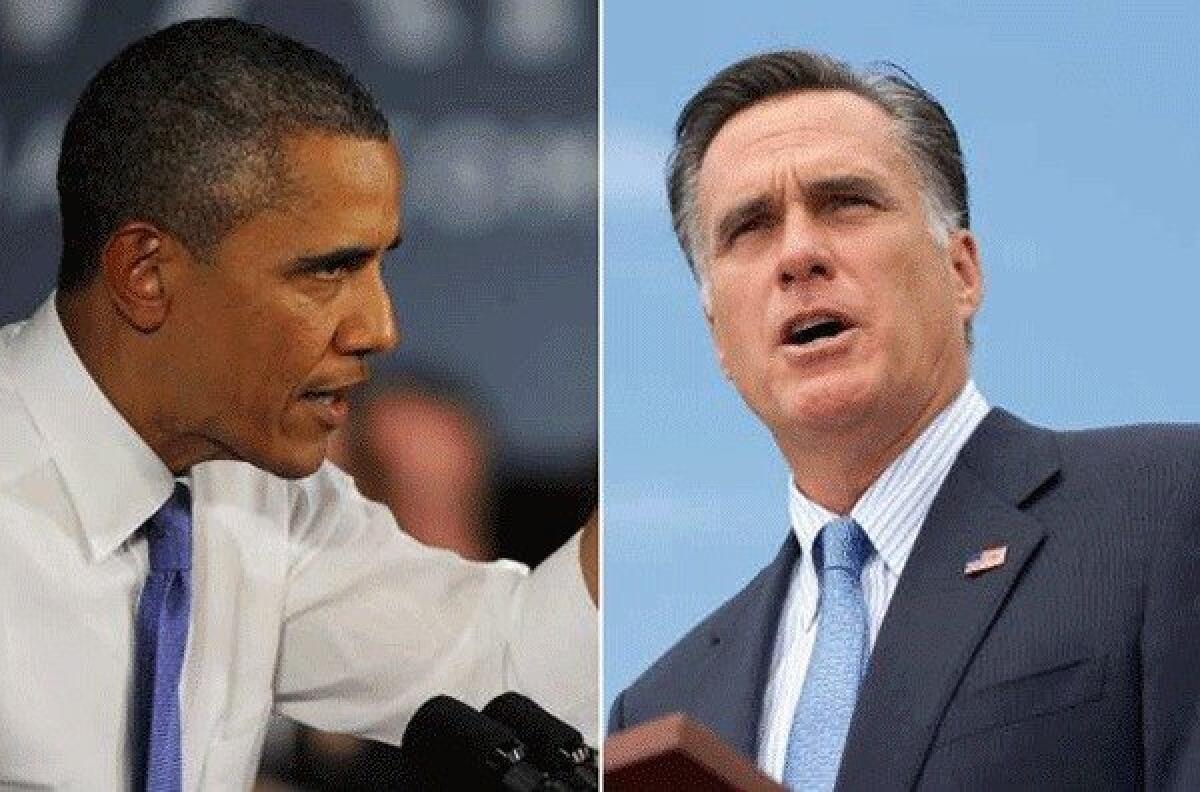

Last week, President Obama accused Mitt Romney not merely of having been “an outsourcing pioneer” but also of currently advocating “tax breaks to companies that are shipping jobs overseas.”

In return, Romney went beyond his old charge that Obama “doesn’t get the free-enterprise system” and accused the president of “denigrating success and achievement.”

COMMENTARY AND ANALYSIS: Presidential Election 2012

But is Obama really anti-achievement? And is Romney really going to send your job to China?

Let’s take Obama first. Romney’s assertion stems from a freewheeling campaign speech the president made this month in which he said: “If you’ve been successful, you didn’t get there on your own…. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business — you didn’t build that.”

If you take the last sentence on its own, it might sound as if the president doesn’t give entrepreneurs credit for hard work. That’s where Romney pounced, insisting that the president had as good as said “that Steve Jobs didn’t build Apple.”

That’s a huge logical leap, and it’s just plain silly. For one thing, Obama often praised the late Jobs for building Apple.

The charge that Romney has engaged in — and still supports — sending U.S. jobs overseas is more complicated, but it’s also not central to the economic debate the candidates should be having.

Some offshoring is inevitable in a

globalized free-trade system. When low-skilled jobs can be done much more cheaply overseas, that’s where the work is going to go. But it doesn’t always follow that this harms the U.S. economy.

Even Obama hasn’t denounced U.S. companies such as Apple that do their manufacturing overseas; instead, he’s praised them for creating high-end design and engineering jobs in the U.S. The best response to offshoring is to promote policies to create better jobs at home and train workers to do them.

That’s a principle both candidates agree on. But in an election year, you won’t hear either one saying they agree on anything. They’d rather squabble than agree, even when their positions are illogical. And that means they often avoid substantive discussions in favor of gotchas.

Take the issue of overseas corporate profits. Romney proposes abolishing the corporate tax on profits that U.S. companies make abroad. Obama has characterized the Romney proposal as a “tax break [for] companies shipping jobs overseas.”

But there are problems with that argument. For one, economists disagree sharply about whether ending taxation of foreign profits would send jobs overseas.

“It’s impossible to know,” Michael Mandel, chief economist at the Progressive Policy Institute, a centrist Democratic think tank, told me. “It could be a plus; it could be a minus. It might have an impact at the margin on some industries, but not others. I think it’s a bit of a red herring.”

Obama’s own deficit commission, chaired by Democrat Erskine Bowles and Republican Alan Simpson, recommended the tax law change that Romney advocates. So did the chairman of Obama’s Export Council, Boeing CEO Jim McNerney.

Besides, Romney is careful about what he is proposing: “Amendments to the tax code need to be crafted in a way that does not encourage corporations to game the system and export jobs or to move their U.S. headquarters abroad,” he said in the economic platform he released last year.

So, if both Obama and Romney are guilty of distorting the other’s economic positions, how far apart are they really?

On some economic issues, the candidates sound remarkably similar. They’re both in favor of cutting the corporate tax. (Romney would cut it from its current 35% to 25%; Obama would cut it to 25% for manufacturers and 28% for everyone else.) They’re both in favor of revitalizing manufacturing and improving job training. They’re both in favor of free trade, mostly. One of Romney’s promises in his 59-point economic plan was to ratify trade treaties with South Korea, Colombia and Panama — something Obama has since accomplished.

On other issues — especially on the major fiscal policies that would shape their budgets and their approaches to governing — the two candidates are sharply divided.

Romney wants to reduce income taxes even beyond the cuts enacted a decade ago byGeorge W. Bush; Obama wants to raise taxes on households making more than $250,000 a year. Romney wants to slash spending on domestic programs and raise spending on defense; Obama wants to cut spending modestly on both. (Romney hasn’t explained how he’d improve job training while cutting the budget beyond saying he’d reduce duplicative efforts.) Obama wants to enforce the Dodd-Frank financial regulations; Romney wants to revoke them, and hasn’t said what regulations he’d put in their place.

Now those are issues worth squabbling about.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.