McManus: Romney’s arithmetic problem

Here’s an issue that hasn’t been debated much in the presidential campaign but ought to be: How much should we spend on defense?

President Obama has proposed keeping the Pentagon budget essentially flat for the next 10 years. Mitt Romney, by contrast, wants to increase defense spending massively — by more than 50% over current levels, according to one estimate. That could mean almost $2 trillion in additional military spending over 10 years.

Romney hasn’t actually proposed a defense budget or offered any specific numbers for his military strategy. But he says he wants core defense spending to reach at least 4% of the nation’s gross domestic product — a big increase over the current level of about 3.2%. And he says the country needs about 100,000 more active-duty military personnel than the current 1.4 million, even though U.S. forces have left Iraq and have begun to withdraw from Afghanistan.

COMMENTARY AND ANALYSIS: Presidential Election 2012

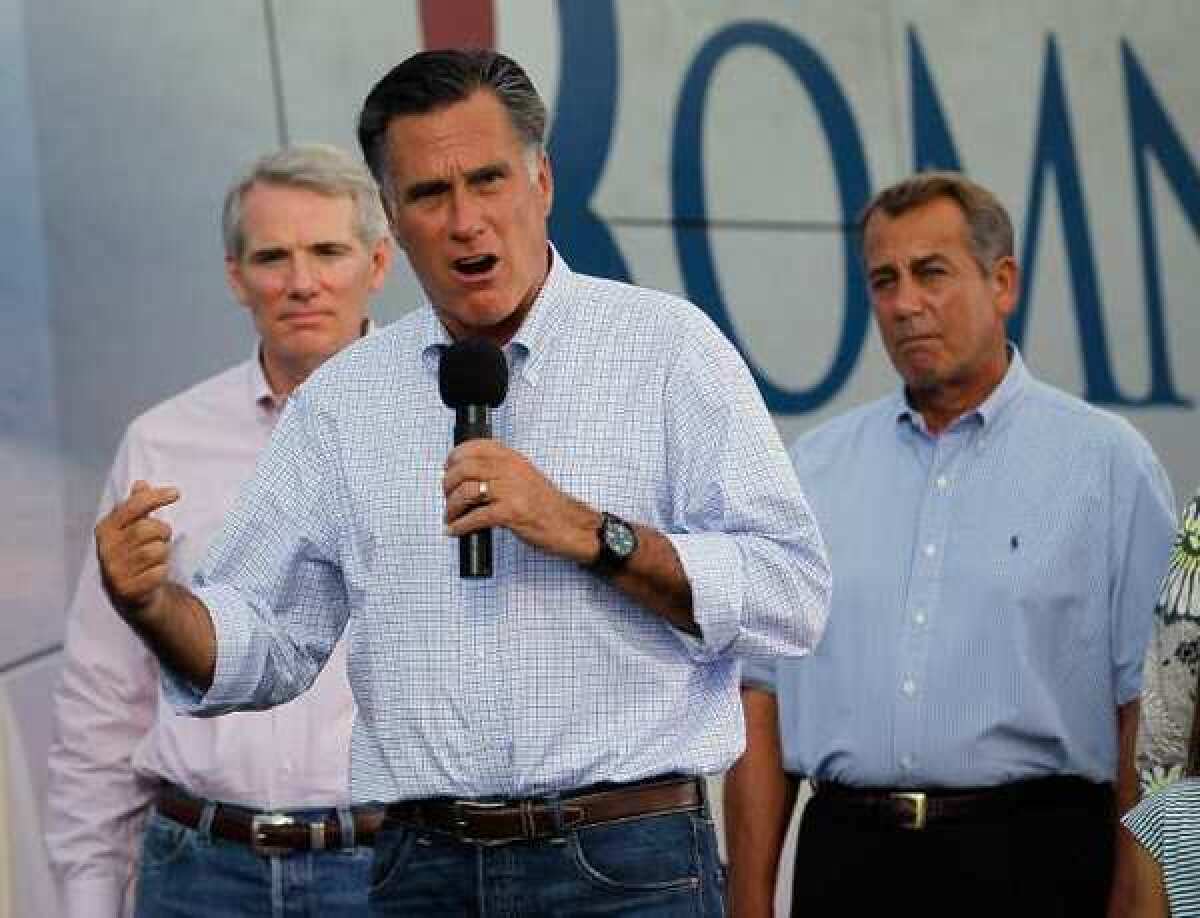

Romney’s argument is that only increasedU.S. militarypower can guarantee peace in the world. “A strong America is the best deterrent to war that has ever been invented,” he told veterans in San Diego last month. He said his goal was “to preserve America as the strongest military in the world, second to none, with no comparable power anywhere in the world.’’

Of course, the United States already fields the strongest military in the world; U.S. core defense spending — that is, the amount we spend on our military excluding the cost of major wars — is already greater than that of the next 10 countries combined. The real questions are: How much is enough? How much can we afford? And in a time of shrinking federal budgets, how would we pay for it?

Let’s start with what’s enough. Romney’s proposal for a defense budget of at least 4% of GDP isn’t outlandish on its face; it’s less than Ronald Reagan spent to help end the Cold War. But the number gives military strategists fits because it’s based on an arbitrary economic benchmark, not an assessment of global threats.

The same is true of Romney’s suspiciously round number of 100,000 for additional military personnel. Where did that number come from? Romney aides won’t say, though they speak about the need for an enlarged Navy and Air Force to deploy in East Asia.

But the biggest problem with Romney’s defense numbers is that they don’t add up with the rest of his platform, which calls for decreasing federal spending overall while also lowering taxes — and, at the same time, balancing the budget.

“My administration will … make the hundreds of billions of dollars in cuts necessary to reduce spending to 20% of GDP by the end of my first term,” Romney said in February. “And then, without sacrificing our military superiority, I will balance the budget.”

A nice trick if he could pull it off, but it flies in the face of, well, arithmetic.

“It’s just not realistic — and that’s being generous,” said Todd Harrison, an analyst at the nonpartisan Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. “It would require a dramatic increase in defense spending to reach these targets. If you combine it with tax cuts and a commitment to avoid cutting Medicare, there’s no way to do it without creating a much higher deficit.”

Harrison crunched the numbers on Romney’s call for a 4%-of-GDP floor on core defense spending. Here’s what he came up with:

Using Congressional Budget Office estimates for future GDP, Romney’s plan would boost core defense spending to about $945 billion in 2021 — about 53% more than the $618 billion proposed in Obama’s defense plan for that year.

One has to wonder, Harrison said, “if this is just a talking point, and if they have actually looked at these numbers themselves.”

I asked a Romney advisor who should know: Dov S. Zakheim, who served as the Pentagon’s chief financial officer in the administration ofGeorge W. Bush. Zakheim said Romney was serious about the goal but hasn’t specified a date for reaching it — and as a result, no specific spending forecast is possible.

“It is a target,” he said. “The sooner we reach it, the better. And we can build up faster as the economy grows.”

“If you look at the last 10 years, 4% isn’t exactly a lot,” he added, noting that the Bush administration spent more when it went to war in Afghanistan and Iraq.

True, but that’s not the issue Romney needs to address. He needs to explain how he plans to balance the federal budget while adding trillions in new military spending.

Romney has been careful all year to avoid being specific about what kind of spending he’d cut — presumably because at some point, he’d have to acknowledge that big budget cuts require reduced spending on Medicare, a dangerous subject to raise with older voters. His plans for a bigger defense budget only make that problem worse.

If Romney wants voters to take his promises seriously, he owes them more details, and soon.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.