Dennis Hopper dies at 74; actor directed counterculture classic ‘Easy Rider’

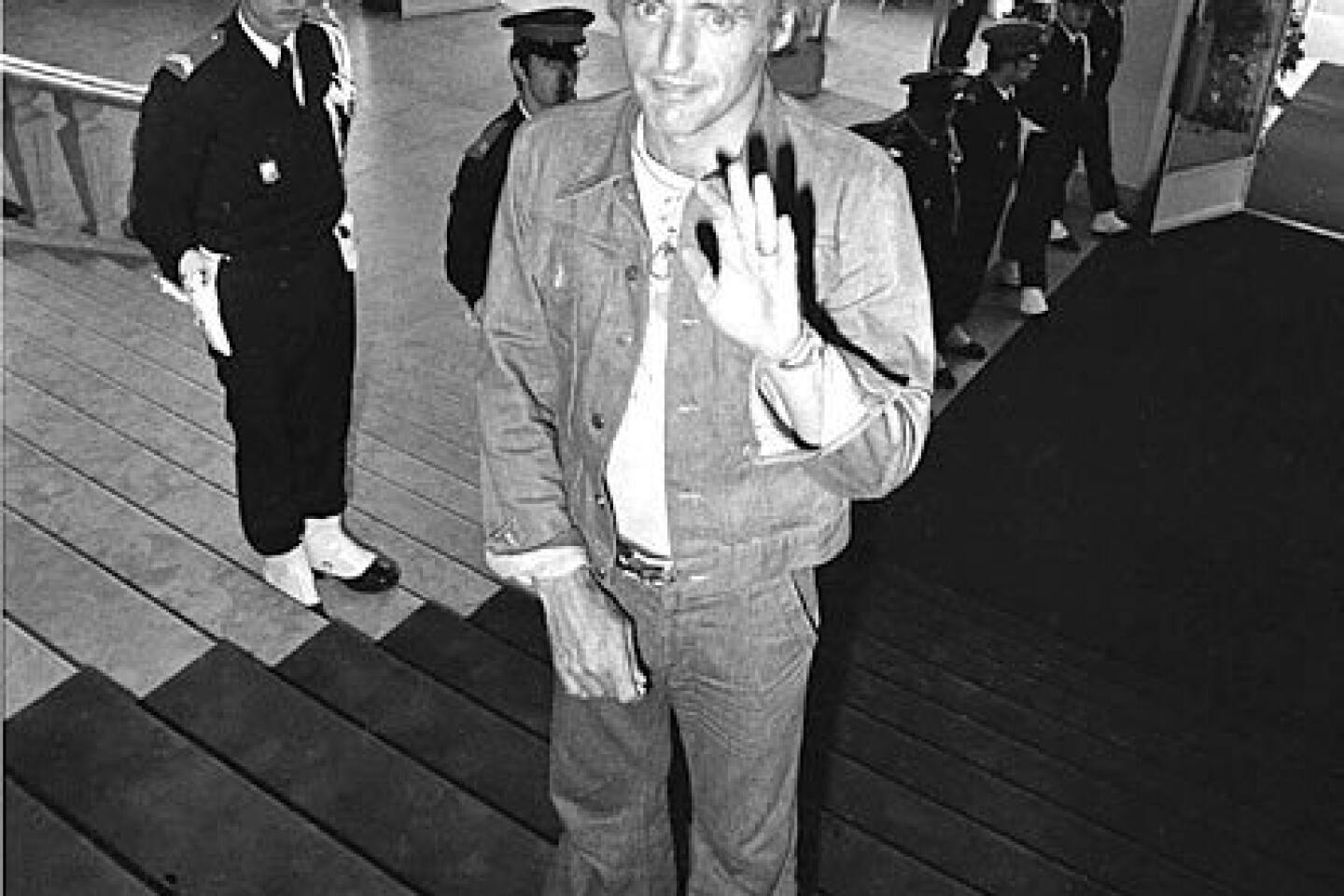

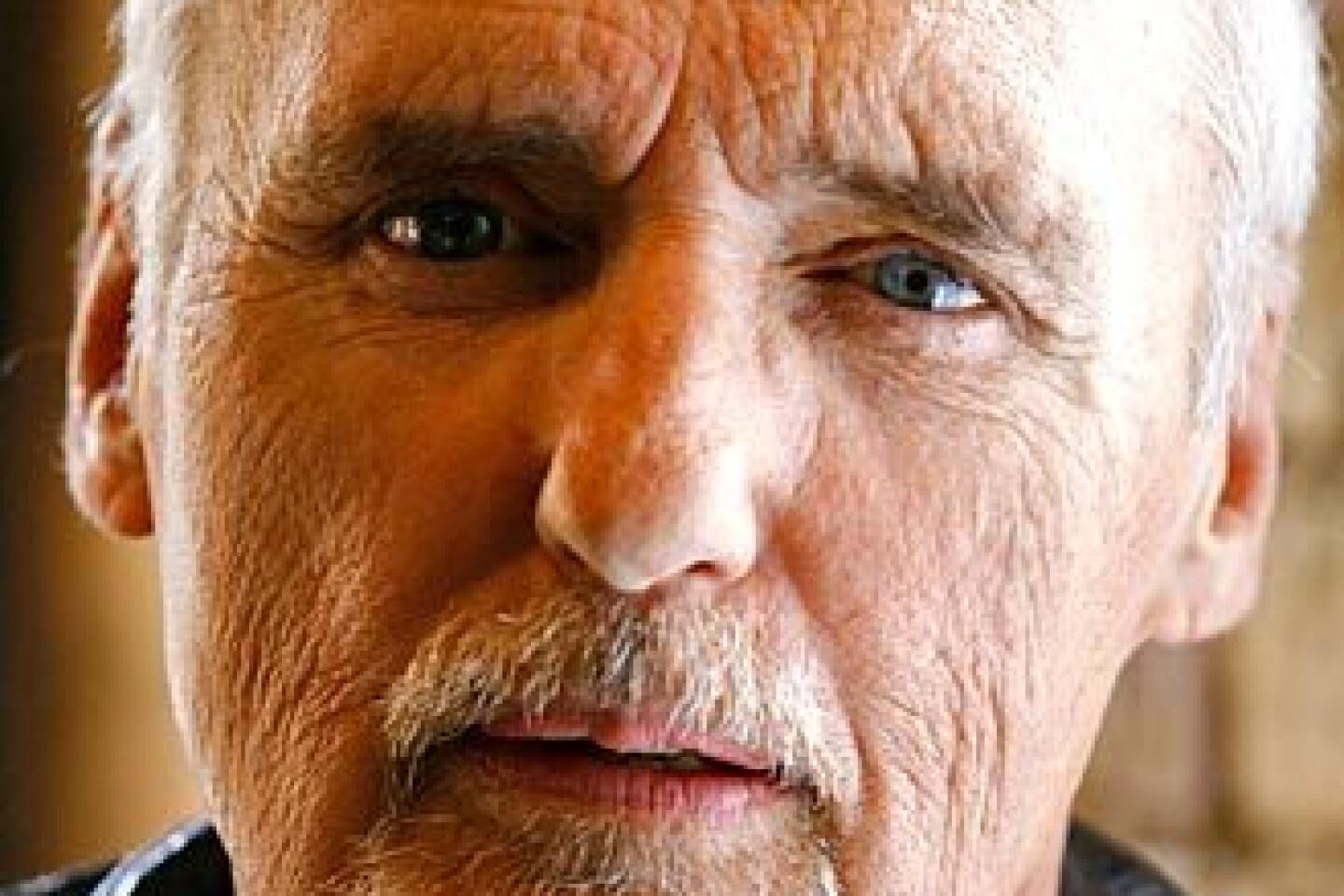

Dennis Hopper, the maverick director and costar of the landmark 1969 counterculture film classic “Easy Rider” whose drug- and alcohol-fueled reputation as a Hollywood bad boy preceded his return to sobriety and a career resurgence in the films “ Hoosiers” and “Blue Velvet,” died Saturday. He was 74.

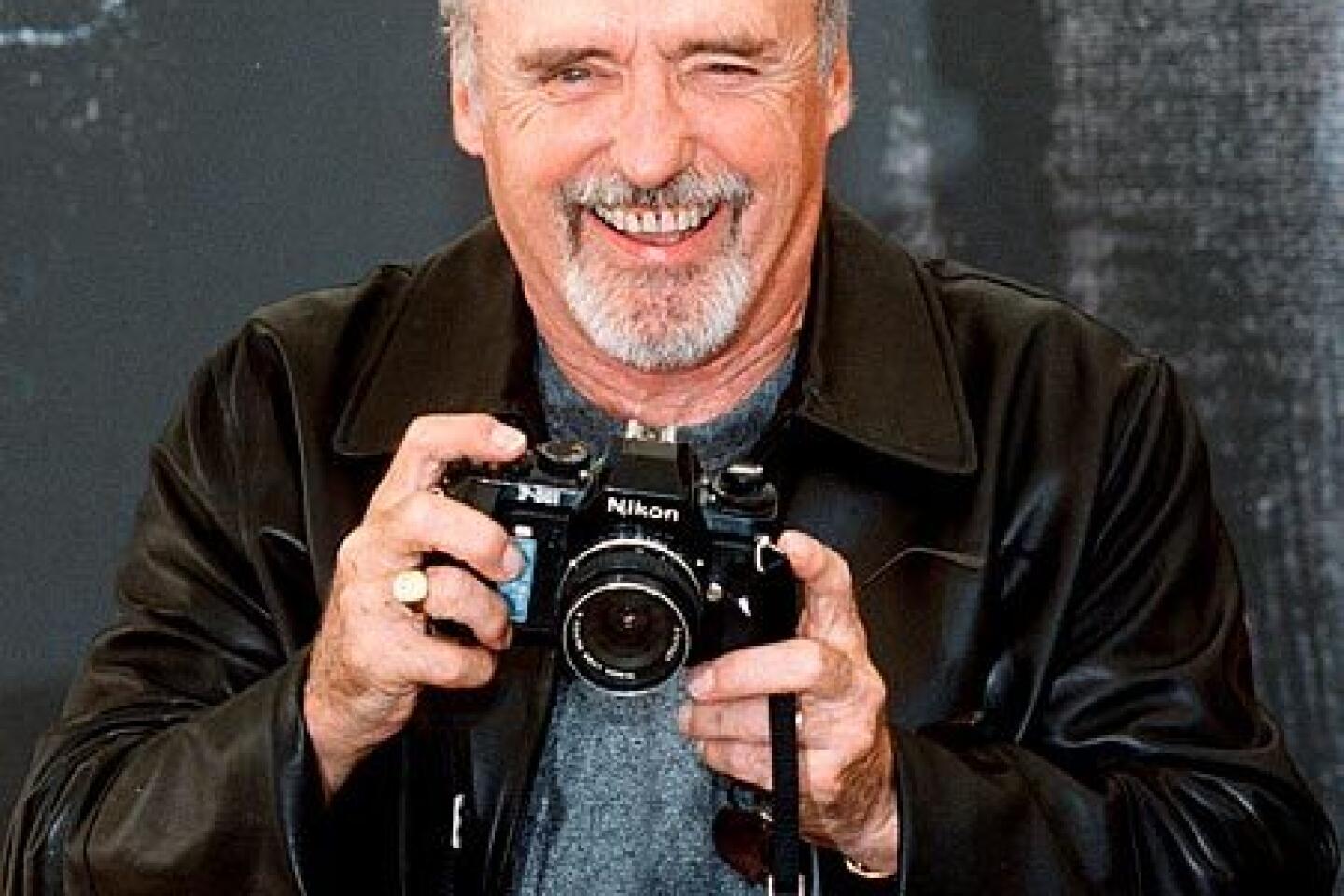

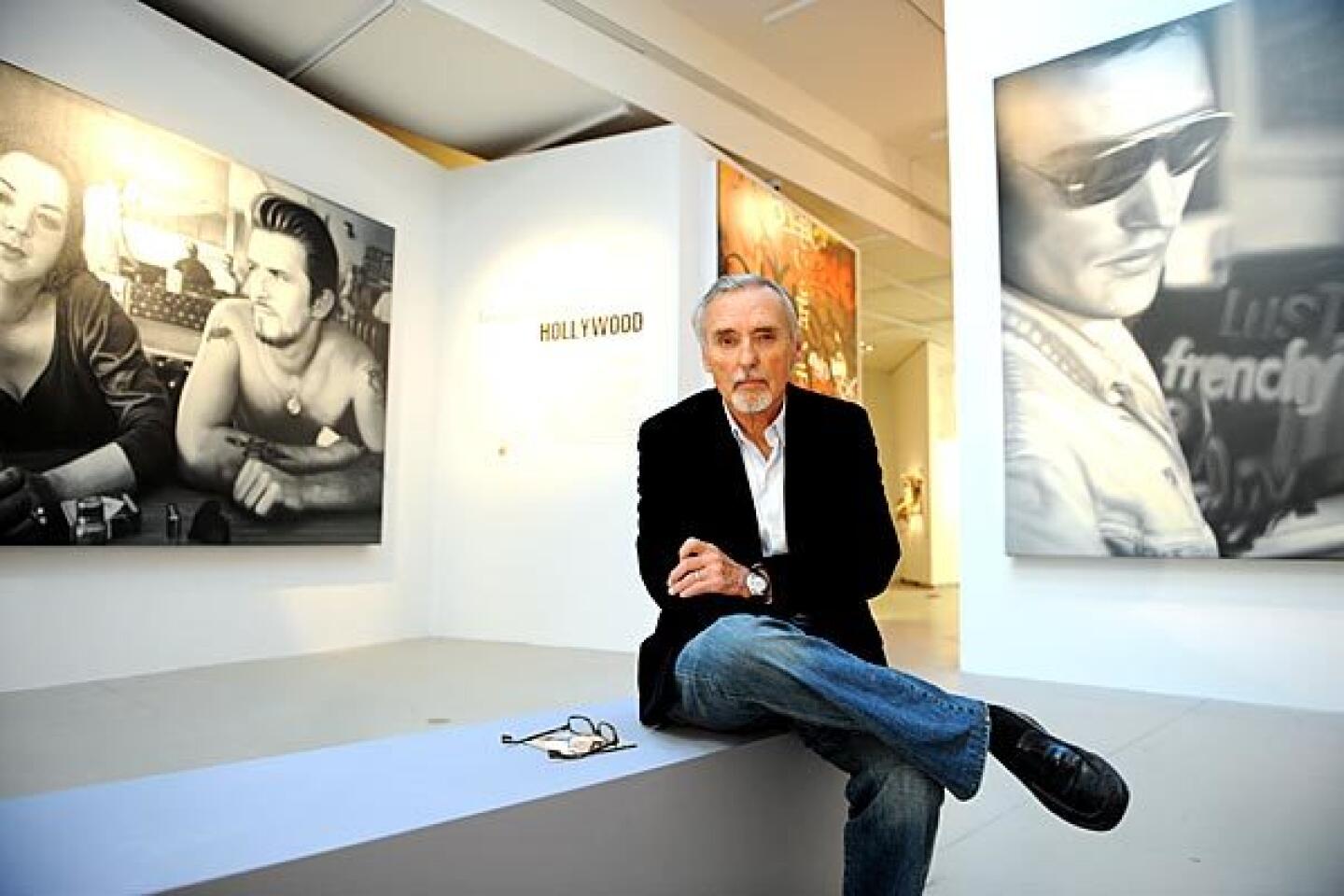

A longtime resident of Venice who also was known as a photographer, artist and collector of modern art, Hopper died at his home of complications from prostate cancer, said Alex Hitz, a friend of the family.

A frail-looking Hopper, whose battle with prostate cancer was revealed in October, was able to attend a ceremony for the unveiling of his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in late March.

In a more than five-decade acting career that was influenced early on by working with James Dean and studying at the Actors Studio, he made his film debut as one of the high school gang members who menace Dean in the 1955 classic “Rebel Without a Cause.”

Hopper went on to appear in more than 115 films, including “Apocalypse Now,” “Cool Hand Luke,” “Giant,” “Hang ‘Em High,” “Rivers Edge,” “Rumble Fish,” “Speed,” “The American Friend,” “True Grit” and “True Romance.”

But it’s his role as the long-haired, pot-smoking biker Billy opposite Peter Fonda’s Wyatt (Captain America) in the hit movie “Easy Rider” that gave Hopper his most enduring claim to fame.

The low-budget tale of two bikers on an ultimately tragic cross-country odyssey after scoring a big cocaine sale, “Easy Rider” became a generational touchstone.

“We rode the highways of America and changed the way movies were made in Hollywood,” Fonda said in a statement Saturday. “I was blessed by his passion and friendship.”

The movie, which boasted a star-making performance from a little-known Jack Nicholson as a boozy small-town lawyer who goes along for the ride and gets his first taste of marijuana, set old-guard Hollywood back on its heels.

“The impact of ‘Easy Rider,’ both on the filmmakers and the industry as a whole, was no less than seismic,” Peter Biskind wrote in his 1998 book “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-And-Rock ‘n’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood.”

“Hopper was catapulted into the pantheon of countercultural celebrities that included John Lennon, Abbie Hoffman and Timothy Leary,” Biskind wrote. “He was surrounded by groupies and acolytes. He may have started down the slippery slope to megalomania and grandiloquence on his own, but he had plenty of help.”

“Easy Rider” won an award at the Cannes Film Festival for the best movie by a new director, and it earned co-writers Hopper, Fonda and Terry Southern an Oscar nomination.

“Hopper and Fonda were renegades, Hollywood-bashers, the Vietcong of Beverly Hills,” Biskind wrote. “To them, it was vindication, beating Hollywood at its own game, proof that you could get high, express yourself and make money all at the same time.”

Commenting on the success of “Easy Rider,” Hopper said: “Nobody had ever seen themselves portrayed in a movie. At every love-in across the country people were smoking grass and dropping LSD, while audiences were still watching Doris Day and Rock Hudson.”

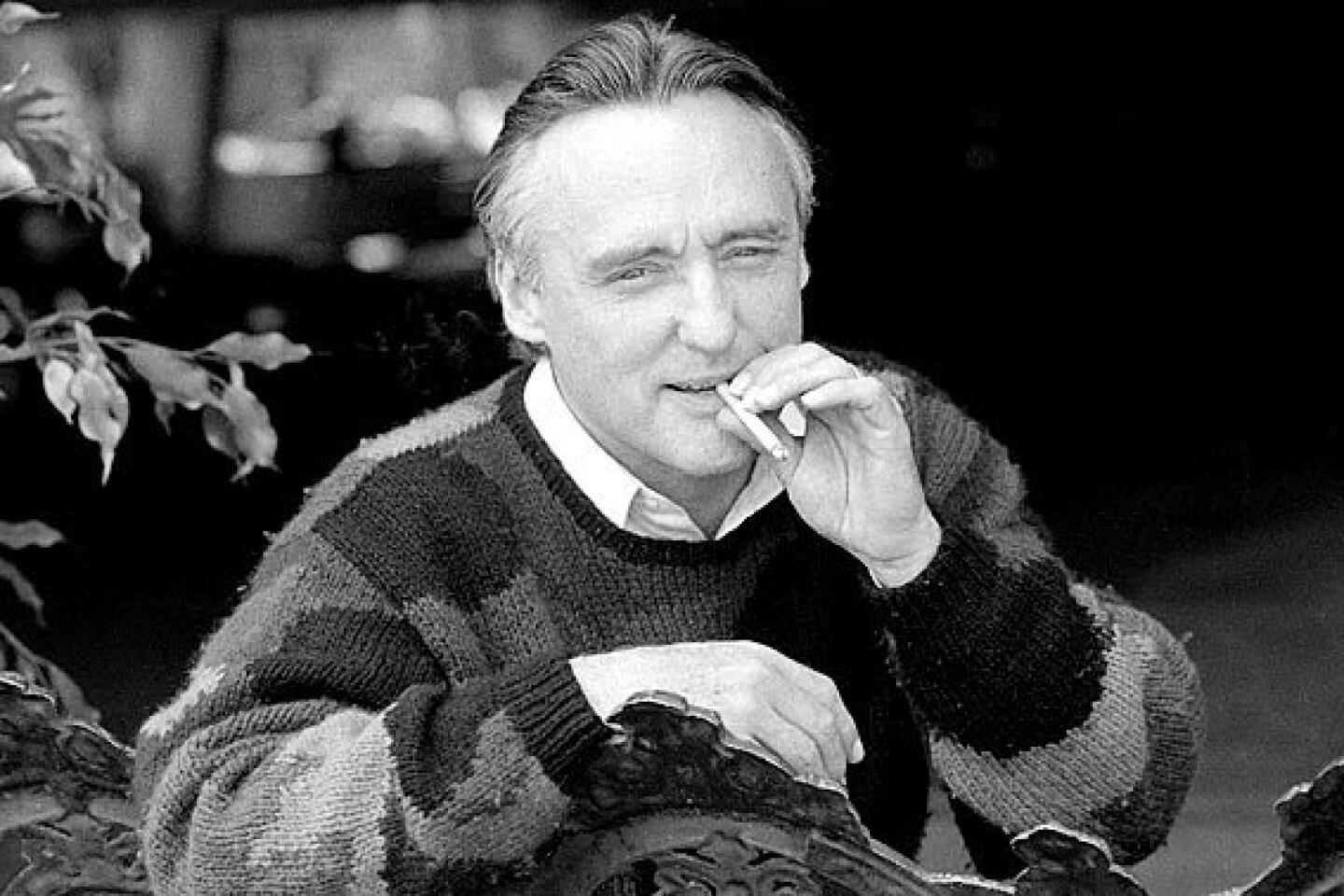

Another signature role was in “Apocalypse Now,” director Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 nightmare vision of the Vietnam War. Hopper played a counterculture photojournalist, who is encountered in the compound of Marlon Brando’s insane, renegade Col. Kurtz and is prone to his own crazed rantings.

“Dennis Hopper was part of that sort of misfit, rebel-persona generation where you just didn’t hit your mark and say your lines and try to create a movie icon type of presence,” said Peter Rainer, film critic for the Christian Science Monitor. “He was much more rough-hewn, rough-edged and intuitive as an actor, and this created a lot of problems early on.”

Indeed, Hopper survived being shut out of major studio films for a number of years after a legendary run-in in the late ‘50s with old-guard director Henry Hathaway on the set of “From Hell to Texas.”

The highly volatile actor also survived his own well-documented descent into drugs and alcohol that reached a low point in the early ‘80s while making a film in Mexico.

“I ended up walking off into the jungle, naked, in the middle of the night, somewhere down near Cuernavaca,” he told Entertainment Weekly in 2005. “I was convinced they were listening to my mind and my friends were being gassed.”

During the last five years of his “abusing,” he said, “I was doing half a gallon of rum with a fifth of rum on the side, 28 beers and 3 grams of cocaine a day — and that wasn’t getting high, that was just to keep going, man.

“I was a nightmare. I finally just shorted out.”

A post-rehab Hopper received a supporting actor Oscar nomination playing, ironically, the alcoholic father of a high school basketball player who sobers up briefly to become an assistant to Gene Hackman’s coach in the inspirational 1986 film “Hoosiers.”

But, as Hopper told The Times, “I’m not usually in one of those movies that leaves you feeling good when you leave the theater.”

That same year he appeared in “Blue Velvet,” writer-director David Lynch’s disturbing film in which Hopper played the mystery-substance-inhaling psychopathic killer Frank Booth, a character Time magazine critic Richard Corliss described as possibly “the vilest sadistic creep in movie history.”

“When people ask what I was inhaling in the mask, I say it was [Method acting teacher] Lee Strasberg,” Hopper later told the London Evening Standard.

As an actor, Hopper carved out his own particular niche as what one journalist called a “serial portrayer of weirdos,” including the maniacal bomber in “Speed” and the eye-patch-wearing villain with the shaved head in “Waterworld.”

Hopper, Rainer observed, “really gets inside the craziness” of such characters.

“He’s able to do that because — and this is where the Method part probably comes in — he somehow taps into the craziness in himself,” Rainer said.

After “Easy Rider,” Hopper was dubbed “Hollywood’s hottest director” by Life magazine. He went to Peru to direct “The Last Movie,” in which he played a movie stuntman who remains in a remote mountain village after a Hollywood film company shoots a violent western whose production has a powerful effect on the villagers.

Released by Universal in 1971 after Hopper spent more than a year editing it at his home in Taos, N.M., “The Last Movie” won the Critics Prize at the Venice Film Festival but was panned by most movie critics and quickly pulled from theaters.

“As a piece of film-making,” summed up Charles Champlin, then The Times’ movie critic, “it is inchoate, amateurish, self-indulgent, tedious, superficial, unfocused and a precious waste not only of money but, more importantly, of a significant and conspicuous opportunity.”

It would be years before Hopper got another chance to direct, most notably the 1988 film “Colors.”

But, as Biskind noted of the period after the high-profile failure of “The Last Movie,” Hopper “did do some acting, and directors learned to work around the drugs.”

Far more prolific as an actor since his mid-’80s career resurgence, Hopper continued to work steadily in films and television.

In 1991, he received an Emmy nomination as lead actor for his portrayal of a murderous Southern racist in the Showtime movie “Paris Trout.”

He also showed up in commercials, including ones for Nike and for Ameriprise Financial in which the old Easy Rider told aging baby boomers that it was “time to redefine” retirement.

Hopper more recently played record producer Ben Cendars in the TV series “Crash.”

He was born May 17, 1936, in Dodge City, Kan., and spent most of his childhood living on his grandparents’ farm. His father served in the Office of Strategic Services during World War II and his mother managed an outdoor swimming pool in Dodge City.

After the war, the family moved first to Kansas City, Mo., and then to San Diego County.

A 1954 graduate of Helix High School in La Mesa, he had acted in school productions and had won a scholarship to the National Shakespeare Festival at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego.

His debut TV role as an epileptic in the TV medical drama “Medic” aired in early 1955 and led to the 18-year-old Hopper being signed to a contract with Warner Bros., by whom he was cast in the role of Goon in “Rebel Without a Cause.”

Hopper thought he was the best young actor in the world, he later said, until he saw Dean in action.

“The man was doing things I couldn’t conceive of,” Hopper said in an interview on “Inside the Actors Studio.”

“He wasn’t doing things that were on the written page. I mean, I could give a great line reading; I could do great gestures. I could preconceive everything, but he wasn’t preconceiving anything. He was improvising. He was doing things that weren’t on the page. He was using his imagination. He was expressing things with his body and through himself that were just way beyond my understanding.”

The last time he saw Dean, who was killed in a car crash in 1955 at age 24, was at the end of working with him on “Giant,” the Texas-set epic in which Hopper played Rock Hudson and Elizabeth Taylor’s sensitive son as an adult.

“The most personal tragedy in my life was Dean,” Hopper said in a 1987 Vanity Fair interview. “I was 19 years old and had such admiration for him.”

Even after Dean’s death, the young actor’s advice stuck with Hopper.

“I was a very good technician,” Hopper recalled in a 1990 interview with the Chicago Tribune, “but Dean was, like, so loose, creating all these wonderful things. So I grabbed him during the ‘Chickie-run’ scene, and threw him into a car, and I said, ‘I thought I was the best, and now I see you, and I know you’re better, and I don’t even know what you’re doing.’ He said, ‘Well, you have to do things, not show them. You have to take a drink from the glass, not act like you’re drinking. Don’t have any preconceived ideas. Approach something differently every time.’ ”

Hopper laughed. “That was the beginning of a lot of problems for me with directors.”

On the set of the 1958 western “From Hell to Texas,” Hopper refused to read his lines and gesture exactly the way the director, Hathaway, demanded in a scene. And, Hopper later recalled, Hathaway had him do take after take from 7 in the morning until about 10 at night before Hopper finally “cracked” and did it the director’s way.

But the damage to Hopper’s movie career was done: Warner Bros. dropped him and, he later said, that was the end of his career in Hollywood.

He moved to New York City, where he studied acting with Strasberg. He also became a professional photographer, shooting portraits for Vogue and other magazines. And he married Brooke Hayward, the daughter of actress Margaret Sullavan and producer Leland Hayward.

Hopper’s Hollywood career was reinvigorated when his old nemesis, Hathaway, gave him a second chance by casting him in a small role in the 1965 John Wayne western “The Sons of Katie Elder” and later in the 1969 Wayne classic “True Grit.”

Hopper also appeared in the low-budget, late-’60s drug movie “The Trip” and the biker film “The Glory Stompers,” but he spent most of the decade making guest appearances on TV shows.

Throughout that period, Hopper told Playboy magazine in 1990, “I was looked on as a maniac and an idiot and a fool and a drunkard. And suddenly, I made ‘Easy Rider,’ man, and the whole world opens up to me.”

Hopper’s art will be the subject of an exhibition planned to open in July at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

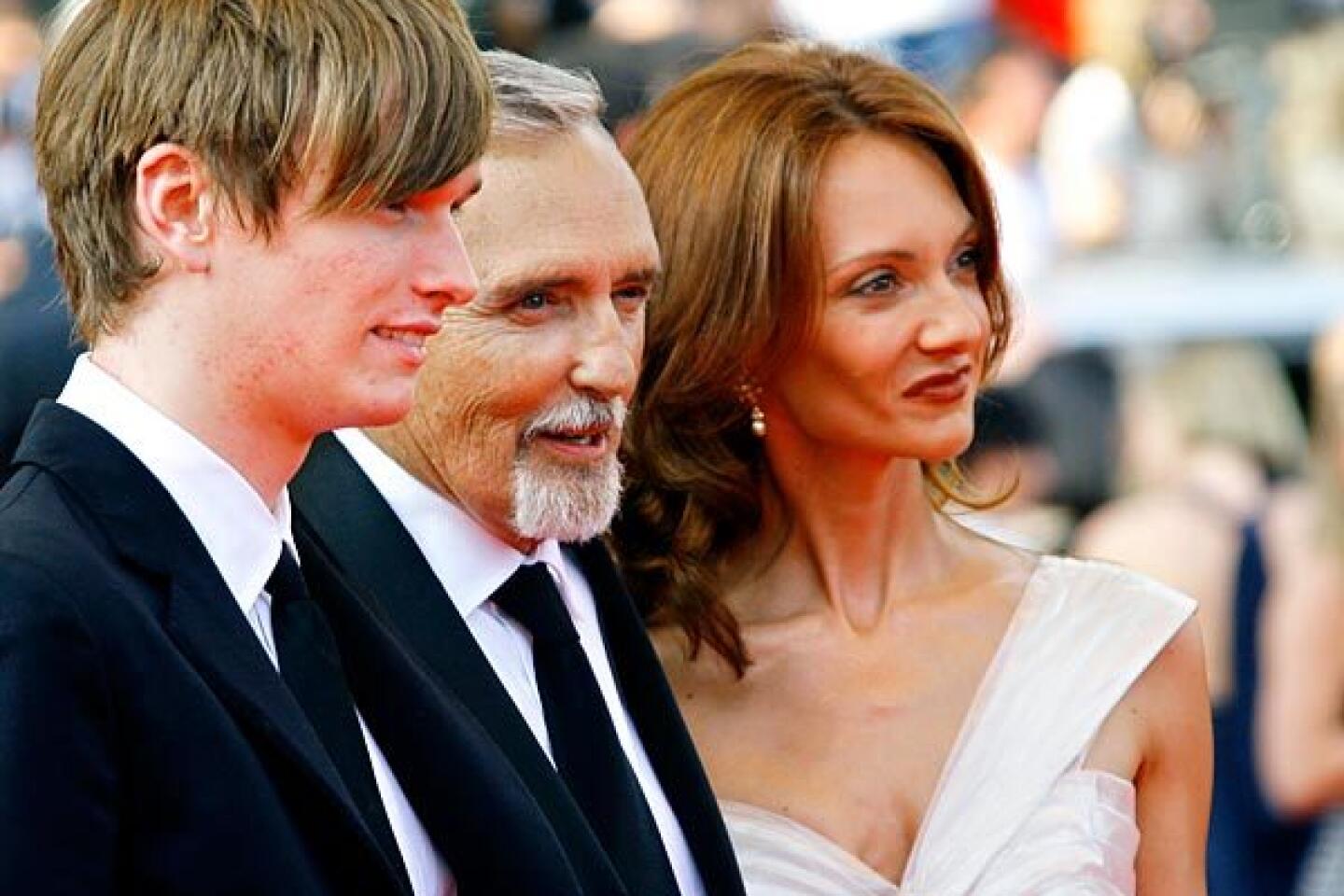

Hopper was married five times — to Hayward, with whom he had a daughter, Marin; Michelle Phillips; Daria Halprin, with whom he had a daughter, Ruthanna; Katherine LaNasa, with whom he had a son, Henry; and Victoria Duffy, with whom he had another daughter, Galen.

In January, Hopper filed for divorce from Duffy, whom he married in 1996. She reportedly stated in court filings that Hopper filed for divorce to cut her out of her inheritance, which Hopper denied.

Hopper’s wife, children and one grandchild survive him, as does his brother, David, Hitz said.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.