Westboro Baptist Church defector struggles with her past

Four years after she fled her family’s gay-hating Westboro Baptist Church, Libby Phelps-Alvarez’s journey is far from complete.

The house was empty, just as Libby Phelps had planned. Slipping inside that afternoon four years ago, she felt as if her heart would burst through her chest.

She peeked through the curtains, terrified that her aunt and uncle across the street would notice the cars parked in the driveway with doors and trunks open.

Moving quickly with three co-workers by her side, she shoved clothes, high school yearbooks, photo albums, a pillow and an old TV into boxes and suitcases. She felt like a thief in her own home. And, in a way, she was.

At age 25, Libby Phelps was stealing her life back.

She never dreamed growing up in Topeka that her last name would become so evil to so many. Her grandfather is Fred Phelps, pastor of the Westboro Baptist Church, a place despised by many for its virulent protests against homosexuality at the funerals of U.S. troops.

For Libby, church and family had always been intertwined. Nearly all of Westboro's 70 members descend from her grandfather. Libby's father, Fred Phelps Jr., is the oldest of 13 children and a church leader. She is one of 55 grandchildren.

The Phelps clan lives in a tight radius only a few blocks wide in central Topeka. The children attend public schools; the adults have professional careers. But they socialize almost entirely with one another.

The Southern Poverty Law Center calls them "arguably the most obnoxious and rabid hate group in America."

From the time she could hoist a sign that read "God Hates Fags," Libby picketed with her grandparents, parents, brother and two sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles, first in Topeka and then across the land. Her family and her faith told her that homosexuality was a sin and she was helping others find the path to salvation.

She believed it with all of her heart.

Until she didn't anymore.

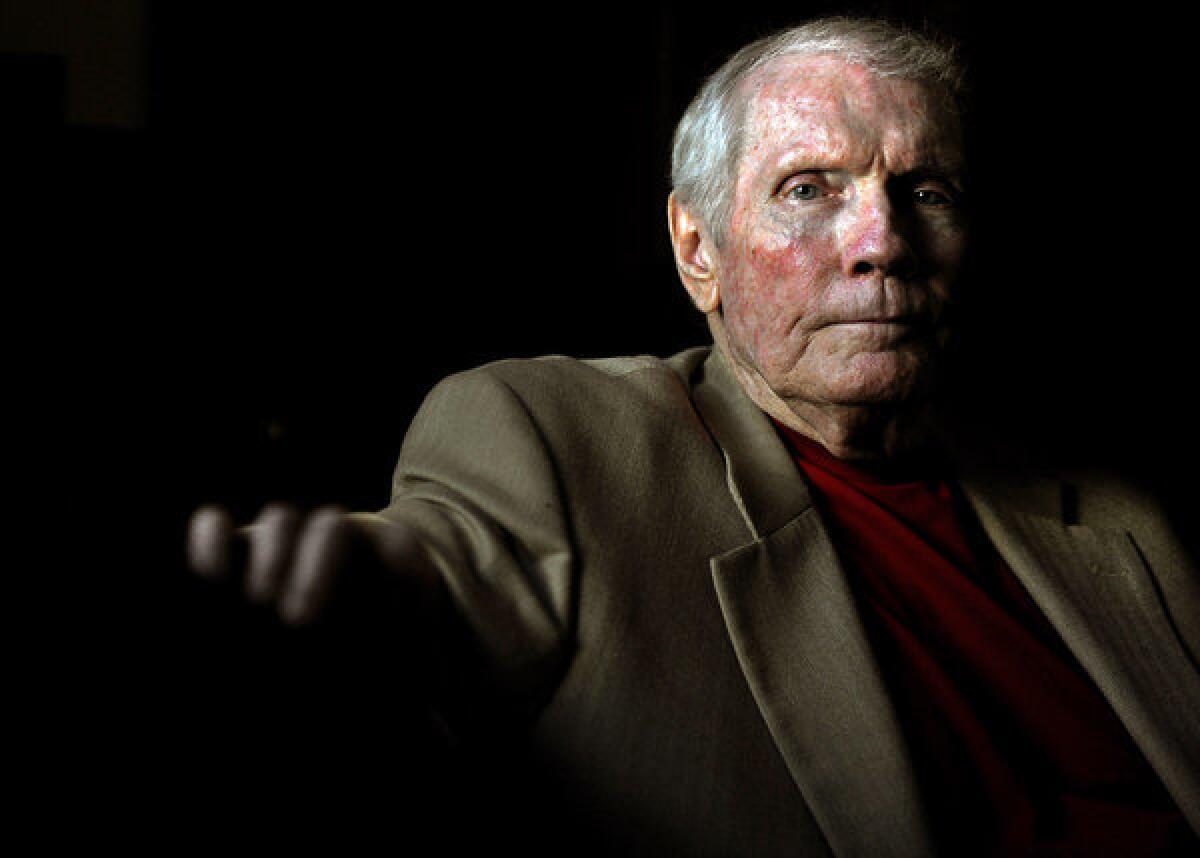

The Rev. Fred Phelps, Libby Phelps' grandfather, leads the controversial Westboro Baptist Church, based in Topeka, Kan. Her father, Fred Phelps Jr., also is a church leader. ( Michael S. Williamson / Washington Post ) More photos

Troubling questions nagged at her as she grew into adulthood: "How could 70 people be right and everyone else be wrong?"

Libby walked one last time through the only house she had ever lived in. Her parents and older sister, Sara, who still lived at home, were out of state picketing. Suddenly her phone started to buzz. It was her mother sending her a text message: "You having a good day?"

She began to cry. Lately the church had questioned her obedience. Her parents suggested she be more contrite. Her grandfather had asked her just a few days before whether she was thinking of leaving. Even as she reassured him, she could not stop herself from forming a plan.

Libby did not answer her mother. She set the phone on her bed and walked out the door. Her parents and grandparents have not spoken to her since.

Libby had grown up with the belief that the world was full of bad people who would do her harm. In the first months of her new life, she was terrified of strangers. She would go to a party and wonder what her parents would say. She would watch people from afar, wanting to fit in but not knowing how. She still has a hard time trusting others.

"Over time, though, I am less and less the person I used to be," she said. Recently, she has set out to visit places she had been before but this time without a picket sign.

She was 12 when the picketing began.

It was the summer of 1991 and her grandfather took two grandsons on a bike ride to a park in Topeka. The park had long been a hookup spot for gays. The family story goes that Fred rode ahead and when he circled back, a man was trying to lure the boys into the trees.

Furious, he went to the city and demanded it clean up the park. When Topeka's government did not act, he posted his first sign on a park restroom door: "Watch Your Kids. Gays in Restroom."

Libby Phelps' parents, Margie, left, and Fred, center, protest in Baltimore in 2007. Libby says she misses her parents but has not had contact with them. ( Jed Kirschbaum / Baltimore Sun ) More photos

He went to local churches for support. He found none.

He became convinced he and his offspring were chosen to battle a modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah. They needed to take their warnings directly to the public. Fred, now 83, describes his church as Old School Baptist and subscribes to the Calvinist belief that certain people are picked for salvation before birth.

In the beginning, Libby saw the picketing as a play date with her cousins. Every week the children carried signs with messages of damnation and trudged around in a circle in Gage Park until a pattern was worn into the grass. Sometimes in the summer it got so hot that Libby's mother would wrap a wet washcloth around her neck. In the winter, getting their snow gear on took longer than the picket.

"I didn't even know what a homosexual was," Libby said.

Before long, her grandfather's crusade expanded beyond Topeka. Family members were dispatched to picket government offices, schools, military bases and pop culture events for what the church perceived as acceptance of homosexuality.

Libby picketed dozens of gay pride parades around the country, the AIDS quilt tour, the Academy Awards, radio broadcaster Paul Harvey's funeral, Jenna Bush's wedding, a public memorial for firefighters in California, college football games, soldiers' funerals, actor Bernie Mac's funeral, a Billy Graham event, the Sago mine disaster funerals in West Virginia and President Obama's 2008 inauguration. She even picketed her high school and college graduations before taking part in the ceremonies.

It had never been easy growing up as a Phelps.

Holidays were not celebrated. She was forbidden to date. She could not wear makeup, pierce her ears or cut her hair. As her family's notoriety grew, she realized she was despised. Classmates would move to the other side of the room to avoid her. Her parents told her persecution made her stronger.

Once, when Libby was 17, Sara asked their parents what they would talk about as a family if they didn't picket.

Libby Phelps pickets against Billy Graham and the Southern Baptist Convention in 2006 in North Carolina. (Megan Phelps-Roper) More photos

"Don't say that. Don't even think like that," Libby recalled their father bristling.

Later that night, maybe for the first time, Libby began to wonder: "Am I doing the right thing? Should I be telling people they are going to hell?" She quickly pushed those thoughts aside.

After the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, she said, church members were jubilant, saying God had punished the United States for condoning homosexuality. But Libby didn't feel happy.

Soon afterward, one of her favorite cousins, Joshua Phelps-Roper, abruptly left the church. She was told to never speak to him again.

Years before, Libby's oldest sister had also left the church. When her sister tried to visit home, church members told her she was not welcome. Libby saw the price of betrayal.

Yet she worried that those around her were becoming more extreme.

In February 2009, a fight over a bikini brought back rebellious thoughts that she had once swatted away.

Libby was working as a physical therapist at the time her family planned a trip to Puerto Rico. A co-worker lent her and her sister bikinis, and their mother snapped a modest picture of the two on a beach.

The photo was displayed on a table before church one Sunday. By the end of the service it was gone.

Libby was accused of dishonoring her parents, and an intervention was called. Church leaders told her they noticed her faith was slipping.

She was afraid, but unlike her sister Sara, she did not apologize. She reminded her critics that other church members had worn bikinis without reprisal. It only made them angrier. She was told she was trying to live in both worlds. She would have to choose.

"What is in your heart?" an aunt demanded.

Libby wasn't sure. Once she figured it out, she knew what she had to do.

Since Libby left Westboro Baptist Church in 2009, there have been about 10 other defections — most of them grandchildren, including Sara.

Steve Drain, a Westboro spokesman, downplays the departures. "They're not of us," he said. "They want to define God in their own terms. Good luck with that." His daughter Lauren left and recently wrote a book critical of the church.

Libby married in July 2011. Her parents did not attend.

Libby Phelps with her boyfriend at the time, Logan Alvarez, in Venice, Italy, in 2010. They have since married. Her parents did not attend the wedding. ( Libby Phelps ) More photos

Her name is now hyphenated: Phelps-Alvarez. Now 30, she lives in Lawrence, Kan., about 20 miles from her childhood home. She has new friends, a new family, a new world. But she misses her parents. Just after she left, she received an email from a church member saying her mother and father wanted no further communication with her. Her parents did not respond to requests for an interview.

Libby isn't sure what she believes anymore. She no longer hates homosexuality, but her journey is far from complete: "Everyone thinks when you leave you do this 180. It doesn't work that way."

Sometimes she and her cousins talk about reaching out to those they hurt. Libby remembers when the Phelps clan picketed the funeral of a soldier killed in Afghanistan in 2006. He was the husband of one of her favorite instructors in college.

Libby wishes she could explain her past to the woman, but what could she say?

"I guess I would say I am so sorry. I thought I was doing the right thing."

She is not yet ready to make the call.

More great reads

Brazil, Japan, sumo and food, deliciously intertwined

An early terrorist in the U.S. condemns today's jihad

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.