Old guard, young blood clash in Salinas’ halls of power

Generations’ worth of racial and class tensions have come to the forefront as a defiant young Latino politician takes on the city’s power brokers. His hero? A 19th century outlaw.

Early evening in the "Salad Bowl of the World" and the City Council meeting is standing room only. The murmur of the crowd drips with anticipation. The bickering has been building for weeks.

"I want to remind everyone," warned the mayor, opening the floor to public comment, "this is not a blood sport. Be respectful when people speak."

He was promptly ignored.

The mayor, less than 100 days in office, was presented with a recall petition. His chief antagonist — a council member who also serves on a school board that recently named an elementary campus after a 19th century bandit and convicted killer — was accused of violating state conflict of interest laws.

Emotional, angry, conspiratorial, the night was marked with the racial and class tensions that have simmered for generations in this agricultural town.

It's a tension now in full view over the actions of two men: a young, defiant Latino politician who has irritated Salinas' power brokers, and a man he admires who has been dead for 138 years.

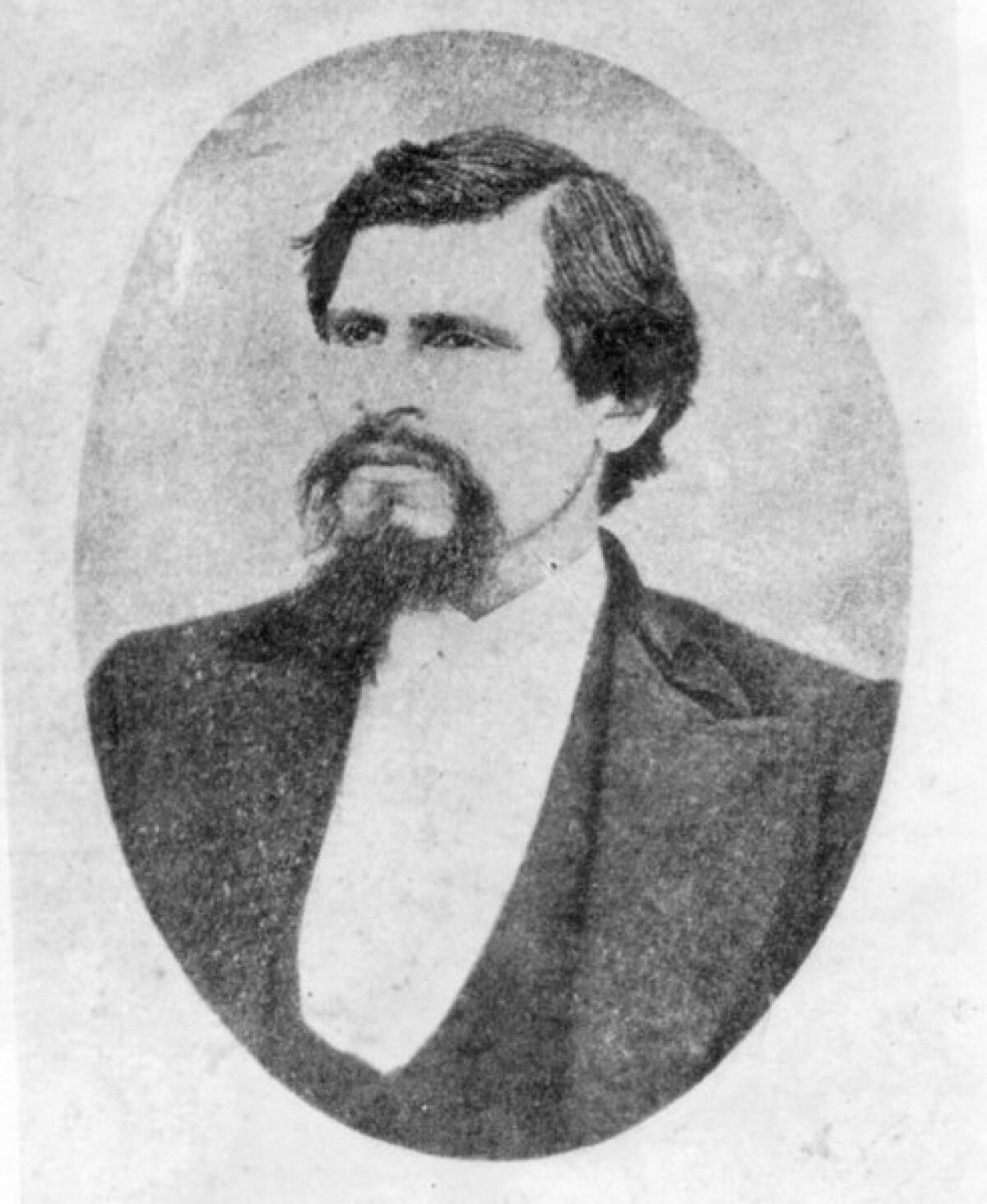

In most ways, Tiburcio Vasquez and newly elected City Councilman Jose Castaneda have nothing in common. But the two men's stories have improbably come together like gasoline and a match to create a fiery political brawl that has divided Salinas for months.

Vasquez is among the most complicated and divisive figures in California history. A descendant of California's Spanish settlers, he turned to crime after the Mexican-American War, which ceded California to the United States.

Educated, handsome and a charismatic ladies' man who wrote poetry, Vasquez the bandit became a celebrity during an era of social and economic upheaval in California.

Moviegoers visit a theater in a new upscale development on the west side of Salinas, the more affluent side of town, in contrast to the east side, which is mostly Latino and working-class. More photos

His exploits — robberies, shootouts, eluding authorities — spawned countless newspaper articles, tell-all books, even a play during his life, which ended in 1875 when Vasquez was convicted of murder by an all-white jury and hanged.

"To the whites, he was an evil Mexican. To Latinos, he was a Robin Hood," said John Boessenecker, a San Francisco lawyer and historian who wrote a biography of Vasquez. "He was a symbol of hope and resistance."

He still is to some. In December the board of the Alisal Union School District voted to name a new campus Tiburcio Vasquez Elementary. It opened last month to serve Salinas' east side, an impoverished, gang-plagued area home to Latino laborers and farmworkers.

"I don't know if he was a thief," said Castaneda, who, as an Alisal trustee, championed naming the school for Vasquez. "I know he was someone who stood up for his rights, stood up for his people."

There were bad things done in Salinas in the past, and we haven't healed from that."—Mayor Joe Gunter

The decision outraged people outside the Alisal, as east Salinas is known locally. Mayor Joe Gunter, a former police homicide investigator, said he was shocked. The Salinas Police Officers Assn. expressed "extreme disappointment." Local media editorials condemned the decision.

"It is difficult to understand why a school would be named for someone hanged for murder," one reader wrote to the Salinas Californian. "Even more so since our weekly headlines sound so much like Tiburcio Vasquez's life."

Like Vasquez, Castaneda is complicated and divisive. The 36-year-old landscaper is seen in the Alisal as a fierce advocate on issues as varied as bilingual education and allegations of police harassment.

Outside the Alisal, Castaneda is a polarizing figure whose more than a decade on the school board has included meetings that required police intervention and a two-year state takeover of the then underperforming elementary school district. The takeover, Castaneda maintains, was unconstitutional because it usurped the voters' will.

Last November, Castaneda surprised civic leaders by beating two establishment-backed opponents for a City Council seat without raising a dime or campaigning publicly.

Salinas City Councilman and school board member Jose Castaneda greets people attending the dedication of the elementary school named for Tiburcio Vasquez. His support for the naming has come under fire. More photos

Castaneda didn't need money. He grew up in the Alisal, where outsiders are treated with suspicion. That two non-Spanish-speaking candidates would lose in a neighborhood where one can walk the streets for an entire day and not hear English spoken seems head-slappingly preordained.

Seven months later, Castaneda has arguably become the most high-profile member of the City Council. Not for what he has done but for what he defiantly refuses to do: give up his school board seat.

The city maintains that holding both seats violates state conflict-of-interest law and plans to sue Castaneda to force him from the school board. When a process server tried to hand him legal papers, Castaneda bolted the council chambers and sped off in a car that appeared to be waiting for him.

"There were bad things done in Salinas in the past, and we haven't healed from that," said Gunter, 66. "I don't look at Mr. Castaneda as a foe or an enemy. I look at him as a young man with a great future."

This seemingly straightforward legal dispute has morphed into something nastier, an echo of the controversy over naming a school for a 19th century outlaw and an illustration of the way Highway 101 has long served as a cultural barrier dividing Salinas.

On the west side is City Hall, police headquarters, the Chamber of Commerce — the centers of power. There's also the National Steinbeck Center, which celebrates a native son who, in his time, angered locals so much that they burned "The Grapes of Wrath" outside the public library.

The east side is Salinas' gritty soul. In the Depression it was home to Filipino farmworkers and unwelcome Okies living in tent camps. Today it's overwhelmingly Latino. Laborers and families crowd into homes, garages and bleak apartment complexes. Officially, 61,000 people — about 40% of Salinas' population — live in the Alisal.

An old parchment print of Tiburcio Vasquez -- bandit to some, hero to others. More photos

A quarter of the population lives below the federal poverty level. Only about a third has graduated from high school. Shootings are common, and most of Salinas' killings involve rival gangs in the Alisal.

Yet eastsiders are fiercely proud of their neighborhood, whose name means "grove of sycamores" in the Chumash Indian language. Whenever an Alisal High grad lands at a prestigious university, the student is hailed as a community hero. The bustling business district has hardly a vacant storefront.

The Alisal embodies a collective memory forged by generations of discrimination, violent labor disputes and voting rights abuses that kept Latinos off the City Council until 1989.

"We're always the underdog," Castaneda said. "There are many injustices that have been happening here for far too long."

When he was a child, Castaneda said, he was a rebellious "straight-F student" who was "flirting with the gang life."

He credits his mother, who ordered him to go work the fields picking onions, with turning his life around. "I made $40 in four days," he said. "That corrected me."

Castaneda speaks in a soft voice that belies his intransigence. In refusing to cede any point, he is apt to quote the Bible and obscure legal codes in the same breath. His opponents call him a bully. He says they're out to get him because he's not "being a good Hispanic, a good Mexican."

"Jose has grown into a force to be reckoned with," said Francisco Estrada, a retired Alisal teacher.

Estrada, 58, is among a group of Latino political activists who call themselves "the coalition" and act as Castaneda's rear guard. Having come of age during the Chicano civil rights movement, its leaders conflate attacks on Castaneda and the naming of Tiburcio Vasquez Elementary School with California's defining narrative of conquest.

"If you stood up for your rights, you were a bandit," Estrada said of Vasquez. "If you took abuse lying down, those were the good Mexicans."

But the political intrigue gripping Salinas isn't simply a matter of brown versus white. Infighting among Latino elected officials has split alliances and engendered feuds.

When county Supervisor Fernando Armenta supported the state takeover of the Alisal school district, Castaneda, a former protege, unsuccessfully sought to recall him.

The two confronted each other recently at a school board meeting. Armenta called Castaneda a "punk." Castaneda said Armenta's wife purposely stepped on his heel, and he filed a police report alleging battery. (The district attorney declined to file charges.)

Men play pool at the Blue Lake in east Salinas. More photos

"You take a bite of the filet mignon," Castaneda says of Latino politicians he's estranged from. "That's how people get on the hook."

The price of resolving Salinas' political imbroglio could be more like a banquet of Kobe beef. A mayoral recall election reportedly would cost the city $500,000. Hauling Castaneda into court would cost thousands more.

This in a city so financially strapped that it's using federal grant money to pay firefighters.

After complaining to the U.S. Department of Justice that the city was violating his civil rights by not appointing him to council committees, Castaneda has been in ongoing consultation with Gunter through a federal mediator.

But the two men seem dug in. Amid the heckling at that recent City Council meeting, several of Castaneda's colleagues practically begged him to quit the school board. Gunter worked hard to maintain order. Castaneda remained resistant, holed up inside his belief that powerful forces in Salinas are out to get him.

"My loyalty is to my community," he said, conjuring up his 19th century hero. "I've never been a person who has quit."

Follow Mike Anton (@mikeanton) on Twitter

More great reads

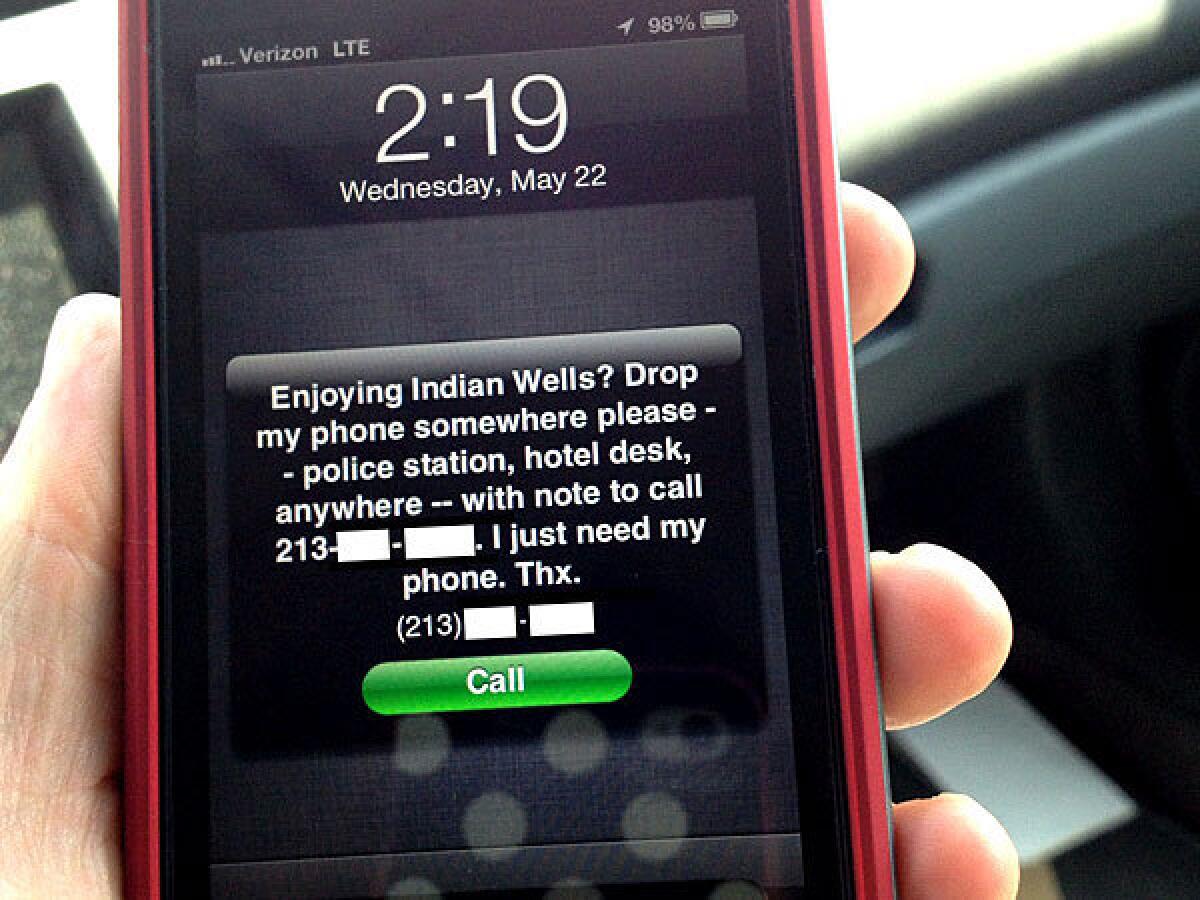

Hot on the trail of a kidnapped iPhone

I'm watching you! Return my phone. ... I'm tracking you. I know where you are."

'Little' Al Robles' big job: Make his own name in politics

People say, 'Why do you do that? People see you hanging around corrupt politicians.' "

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.