Gov. Brown will mean business on his weeklong trip to China

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Jerry Brown is stepping back onto the world stage.

After two years largely spent cloistered in California tending to the fiscal crisis, he starts a weeklong visit to China on Tuesday in a bid to reclaim the state’s reputation as a global economic powerhouse and innovator.

The visit will lack the glitz of Brown’s travels as governor decades ago, with rock star companions and international paparazzi replaced by dozens of state bureaucrats and business officials.

While abroad, Brown plans to sign pacts forging government research partnerships and limiting Chinese greenhouse gas emissions. He’ll announce deals involving California clean-technology companies — electric vehicle makers, a firm that converts trash to electricity — and reinforce his mantra that good environmental policy is good economics.

But mostly, Brown hopes the trip will translate into Chinese money for California.

“We’re going to facilitate billions of dollars of investments,” the governor predicted during a speech in Sacramento last week. “Not overnight, but over time.”

Some experts said Brown’s foray could help make Chinese companies feel welcome in the U.S. at a time when the federal government is sending mixed signals.

Last year, the Obama administration blocked an attempt by a Chinese company to acquire four Oregon wind farms, citing national security concerns. An October report from the House Intelligence Committee said U.S. companies should not do business with Chinese telecom firms, suggesting such deals could put U.S. customer data in the hands of Chinese officials.

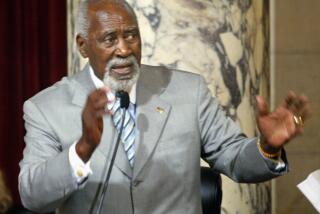

The governor “really needs to lay out the welcome mat and tell them California welcomes Chinese involvement and Chinese investment,” said Orville Schell, director of the Asia Society in New York and author of a 1978 biography of Brown. “It’s a very important symbol that the governor himself is delivering this message. It’s a genuflection.”

At the same time, the “green” pacts Brown signs with the Chinese — albeit nonbinding — will allow him to claim progress with one of the world’s largest polluters where other governments have hit roadblocks, burnishing his reputation as an environmental leader.

His primary focus, however, will be dollars and cents. According to figures from China’s Ministry of Commerce, that country’s investment abroad reached $77.6 billion last year — a sixfold increase since 2005. By the end of the decade, some predict, the figure will triple.

California has lagged in attracting that money. A study by the Asia Society estimates that $1.3 billion in Chinese money was invested in the state in 2011. Brown is eager for much more.

He wants the Chinese to help fund California’s $68-billion bullet-train project, for example. He broached the subject with President Xi Jinping, who was vice president when the two met in Los Angeles last year.

But competition for China’s money is intense, with governments and corporate leaders jockeying for favor. Several years of recession have limited the availability of funding they have typically relied upon from banks and venture capital firms elsewhere.

Schell said he had told the governor “he’s got to get his hand in that honey pot.”

Such an effort will require Brown to suppress his distaste for protocol and other formality as he meets with China’s new commerce minister in Beijing, attends a banquet lunch in Shanghai and addresses 300 California and Chinese business leaders at the home of U.S. Ambassador Gary Locke.

He will also have to deal with some tricky politics. As he opens a new state trade office in Shanghai on Friday, Brown will reignite a decade-old controversy about the role Sacramento should play, and the money it should spend, promoting California overseas.

Ten years ago, state lawmakers closed a dozen state offices from Armenia to South Africa amid questions about their usefulness and revelations that many international deals the state took credit for never came to fruition.

Those involved say the China trade office will operate differently. It will be financed by private companies, not taxpayer dollars. And its mission will be to attract foreign investment rather than simply market California products.

“There is a heightened focus on inbound investment to California,” said Jim Wunderman, president and chief executive of the Bay Area Council, which is sponsoring the governor’s trip and is hoping to raise $1 million to keep the trade office open. “There’s a desire in China to invest in foreign soil, and that represents a huge opportunity for California.”

Some are skeptical: In the past, trade offices have been used as mini-embassies, where governors rewarded political allies and large donors with prestigious appointments.

Donations for the new China office are made to a nonprofit established by the Bay Area Council that is not subject to public disclosure laws. Wunderman said he planned to make a list of those companies public, but he did not provide names of those who had donated so far.

Jock O’Connell, an advisor with Beacon Economics and critic of foreign trade outposts, said wealthy donors don’t really need help from a trade office; they can open their own doors to business in China. It’s smaller fish who typically benefit from such an operation.

“The companies that are well-funded enough to finance this office are not the same companies who would need the services of the office,” O’Connell said. “I’m not sure what these donations are for, other than currying favor with the governor.”

About 90 delegates traveling with Brown each paid $10,000 to go along. The tab covered their costs and those for Brown, his wife and eight other state officials.

The group includes executives from Disney and Sea World who will join the governor in soliciting Chinese tourism for California. Also on the tour are lobbyists and industry officials who are among the governor’s biggest political contributors.

State officials accompanying Brown include Matt Rodriquez, head of the state Environmental Protection Agency, California Energy Commission chairman Robert Weisenmiller and Dan Richard, head of the state’s high-speed rail board.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.