Latin music star Jenni Rivera believed dead in plane crash

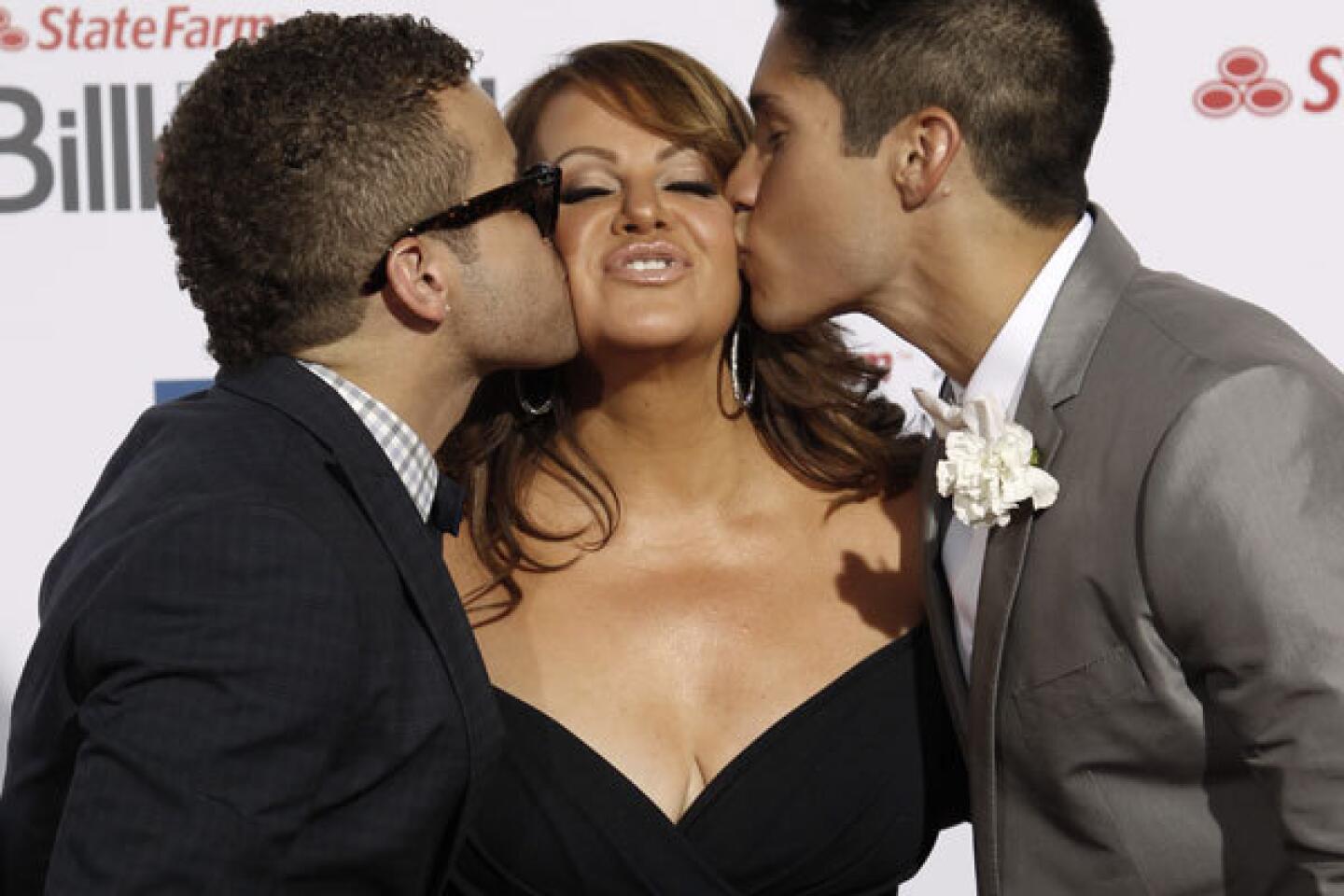

MEXICO CITY — Mexican American singer Jenni Rivera, the “diva de la banda” whose commanding voice burst through the limits of regional Latin music and made her a cross-border sensation and the queen of a business empire, was believed to have died Sunday when the small jet carrying her and members of her entourage crashed in mountainous terrain.

Rivera, a native of Long Beach, was 43. Mexico’s ministry of transportation did not confirm her death outright, but it said that she had been aboard the plane and that no one had survived the crash. Six others, including two pilots, also were on board.

“Everything suggests, with the evidence that’s been found, that it was the airplane that the singer Jenni Rivera was traveling in,” said Gerardo Ruiz Esparza, Mexico’s secretary of communications and transportation. Of the crash site, Ruiz said: “Everything is destroyed. Nothing is recognizable.”

Word of the accident ricocheted around the entertainment industry, with performer after performer expressing shock and grief. Fans gathered outside Rivera’s four-acre estate in Encino.

“She was the Diana Ross of Mexican music,” said Gustavo Lopez, an executive vice president at Universal Music Latin Entertainment, an umbrella group that includes Rivera’s label. Lopez called Rivera “larger than life” and said that based on ticket sales, she was by far the top-grossing female artist in Mexico.

“Remember her with your heart the way she was,” her father, Don Pedro Rivera, told reporters in Spanish on Sunday evening. “She never looked back. She was a beautiful person with the whole world.”

Rivera had performed a concert in Monterrey, Mexico, on Saturday night — her standard fare of knee-buckling power ballads, pop-infused interpretations of traditional banda music and dizzying rhinestone costume changes.

At a news conference after the show, Rivera appeared happy and tranquil, pausing at one point to take a call on her cellphone that turned out to be a wrong number. She fielded questions about struggles in her personal life, including her recent separation from husband Esteban Loaiza, a professional baseball player.

“I can’t focus on the negative,” she said in Spanish. “Because that will defeat you. That will destroy you.... The number of times I have fallen down is the number of times I have gotten up.”

Hours later, shortly after 3 a.m., Rivera is believed to have boarded a Learjet 25, which took off under clear skies. The jet headed south, toward Toluca, west of Mexico City; there, Rivera had been scheduled to tape the television show “La Voz” — Mexico’s version of “The Voice” — on which she was a judge.

The plane, built in 1969 and registered to a Las Vegas talent management firm, reached 11,000 feet. But 10 minutes and 62 miles into the flight, air traffic controllers lost contact with its pilots, according to Mexican authorities. The jet crashed outside Iturbide, a remote city that straddles one of the few roads bisecting Mexico’s Sierra de Arteaga national park.

Wreckage was scattered across several football fields’ worth of terrain. An investigation into the cause of the crash was underway, and attempts to identify the remains of the victims had begun.

Rivera, a mother of five and grandmother of two, was believed to have been traveling with her publicist Arturo Rivera, who was not related to her, as well as with her lawyer, hairstylist and makeup artist; reports of their names were not consistent. Their identities were not confirmed by authorities. The pilots were identified as Miguel Perez and Alejandro Torres.

In the world of regional Latin music — norteño, cumbia and ranchera are among the popular niches — Rivera was practically royalty.

Her father was a noted singer of the Mexican storytelling ballads known as corridos. In the 1980s he launched the record label Cintas Acuario. It began as a swap-meet booth and grew into an influential and taste-making independent outfit, fueling the careers of artists such as the late Chalino Sanchez. Jenni Rivera’s four brothers were associated with the music industry; her brother Lupillo, in particular, is a huge star in his own right.

Born on July 2, 1969, Rivera initially showed little inclination to join the family business. She worked for a time in real estate. But after a pregnancy and a divorce, she went to work for her father’s record label and found her voice, literally and figuratively.

She released her first studio album in 2003, when she was 34.

Her path had not been easy, but rather than running from it, she wrote it into her music — domestic violence; struggles with weight; raising her children alone, or “sin capitan,” without a captain. She was known for marathon live shows that left audiences exhilarated and exhausted; by the fifth hour of one recent performance, she was drinking straight from a tequila bottle and launching into a cover of “I Will Survive.”

In a witty and sometimes baffling stew of Spanish and English, she sang about her three husbands, about drug traffickers, in tribute to her father, in tribute to her gynecologist.

She became, in a most unlikely way, a feminist hero among Latin women in Mexico and the United States and a powerful player in a genre of music dominated by men and machismo. Regional Mexican music styles had long been seen as limiting to artists, but Rivera shrugged off the labels and brought traditional-laced music — some of which sounded perilously close to polka — to a massive pop audience.

“She was one of the people who led the movement, especially by bringing in a woman’s voice,” said Javier Gonzalez, 50, a clarinet player with the Banda Sinaloense Sangre Kaliente in Mexico City. “She held a very privileged place in the genre.”

Rivera had seven top 10 hits on the Latin charts and in September 2011 became the first female regional Mexican artist to sell out Staples Center in Los Angeles. In all, she sold more than 20 million albums and bought her seven-bedroom, 11-bathroom Encino estate in 2009 for $3.3 million.

Her business empire, meanwhile, was growing rapidly. She had a weekly radio program, had recently launched clothing and cosmetics lines and appeared poised to become a bilingual television and film star.

She was the executive producer of a reality show that centered largely on her eldest daughter. The show ran on Telemundo’s sister network, Mun2, and turned the Rivera family into something akin to the Kardashian clan. Three more reality shows followed, including “I Love Jenni,” which offered a glimpse into Rivera’s often chaotic life.

English-language broadcast television was next: ABC confirmed that it was developing a family comedy that would star Rivera.

“She was an amazingly smart businesswoman,” said Lopez, the Universal Music executive. “She was a ball buster when it came to her deal negotiations and anything that would have to do with granting us rights. She was tough. She knew how to take care of her career. There was no manager. The manager was Jenni. She did it all, A to Z.”

Rivera was also jumping into movies. She made her film debut in the family drama “Filly Brown,” shown at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. For acting in the film, Rivera accepted a small paycheck and gave it away — and spent three weeks holed up with an acting coach to prepare for the role.

Did she complain? “Never a peep,” said Youssef Delara, the film’s co-director.

“I was prepared for her to not be so gracious and open to learning from others,” Delara said. “That was the sort of thing that was really surprising, to see someone that established — the humility she brought to it and the desire to be not just good but great at whatever she did.”

Gold and Martens reported from Los Angeles and Fausset from Mexico City.

Times staff writers Meg James, Amy Kaufman, Yvonne Villarreal and Daniel Hernandez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.