Amber Alert jolts cellphones across California

On a narrow road etched through the chaparral east of San Diego, firefighters made a terrible discovery Sunday — a home was on fire and inside was the body of a 44-year-old woman. Missing were the woman’s children and the owner of the home, who was believed to have abducted them.

Nearly 600 miles to the north, in Sacramento, Joe Curren and his girlfriend popped a disc of “Identity Thief” into the DVD player and prepared for a relaxing evening at home. At almost 11 p.m. Monday, his cellphone erupted with a squeal he had never heard before — “like a fire alarm,” he said.

It was the sound of the future, and Curren didn’t like it.

For the first time, California had notified the public of an Amber Alert — a suspected child abduction — through the state’s cellphone network. Like many others throughout the state, Curren was left with two questions, summed up as Will the children be OK? and What am I supposed to do from my couch, near midnight, at the other end of the state?

“This is among the most unintelligent, histrionic, intrusive programs ever,” Curren said. “I felt like the San Diego police reached into my pocket.”

The Amber Alert was issued Monday after firefighters in the tiny community of Boulevard, Calif. — about 50 miles east of San Diego and five miles north of the Mexican border — found the body of Christina Anderson of Lakeside. A child’s body was also found in the wreckage of the burning home.

Authorities allege that the owner of the home, James Lee DiMaggio, 40, killed Anderson and abducted her daughter Hannah Anderson, 16, and son Ethan, 8. The California Highway Patrol said DiMaggio could be headed to Texas or Canada in a blue Nissan Versa.

Seeking the public’s help in locating DiMaggio and the children, officials issued a notification to the vast majority of cellphones in California — the first time the state has used a new, national Amber Alert system administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The Amber Alert program was created in 1996 in memory of Amber Hagerman, 9, who was abducted and killed near her home in Texas. For years, the alerts went out through radio, television or on familiar roadside signs, 700 of which are positioned alongside highways and thoroughfares in California.

But the nation is an increasingly mobile place. More than 90% of adult Americans have a cellphone, and many of those devices are not just phones, but delivery systems for information. A wireless Amber Alert program was launched in 2005. Two critical changes came at the beginning of this year.

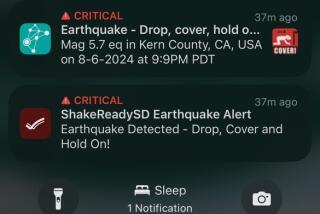

Rather than being sent as text messages, the alerts were transmitted on an exclusive frequency that can reach tens of thousands of people at the same time — even if those people are crowded into one place, such as a stadium, and even, as some users discovered this week, if a cellphone is set to silent.

And cellphone users were automatically signed up unless they decided to opt out of the program. Under the old opt-in system, the alerts reached fewer than 800,000 people, said Brian Josef, assistant vice president of regulatory affairs for the Wireless Assn., a nonprofit trade organization. Now the alerts can reach 97% of the 300 million-plus active cellphones in the United States.

The new system has been used at least 20 times in 14 states, including Pennsylvania, Texas and Ohio. And it has worked; last month, a missing 8-year-old boy in Cleveland was found after a man received an alert on his cellphone, saw the car described by authorities and followed it until police arrived.

Police are only authorized to send out alerts for kidnapped children. Local law enforcement agencies work with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to determine whether an alert should be issued and what geographic area should be covered. Monday’s alert was sent out by the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department.

It’s part of a cascade of programs in which government agencies are harnessing mobile technology to reach many people, urgently.

Last year, as Hurricane Sandy approached, New Yorkers received phone messages telling them to find shelter. This spring, alerts from the National Weather Service popped up on phones as a massive tornado approached Moore, Okla. In California, scientists are developing a system that would give as much as 50 seconds warning before the Big One reached downtown Los Angeles from the San Andreas fault.

The president also has the authority to send an alert in times of crisis.

“We’re harnessing the power of mobile devices that are ubiquitous at this point,” Josef said. “It enhances the chances of saving lives.”

Some people who criticized Monday’s Amber Alert said they understand the need during natural disasters and major events that effect large areas. But they didn’t think it merited statewide distribution.

Across the nation, officials have fielded concerns that the alerts have startled, perplexed and annoyed people. On Tuesday, some users reported receiving the same message numerous times — and in the middle of the night, though many of the messages were preceded by a loud tone, similar to an emergency broadcast on TV.

Others didn’t receive it, although in theory they were supposed to. Some tried to opt out of the program but struggled to do it. Some questioned the system’s efficiency and efficacy — and viewed it as an example of sinister government overreaching, akin to recent revelations about secret government surveillance programs.

“It’s a privacy intrusion, to in effect attempt to make people into informants or law enforcement subagents,” said Herb Pounder, who received the alert Tuesday in Castaic. Pounder said he is “sympathetic toward the children,” but “concerned with what I see as a movement toward a police state in this country.”

Starting just after 11:30 p.m. Monday, Renae Bowman said, she received the alert 12 times. The alerts didn’t stop until the Granada Hills resident finally figured out how to disable them at 7:15 a.m. Tuesday.

“If I only get it once, I think it’s an amazing idea,” said Bowman, 25.

Among those who received the alert — twice — was Marc Klaas, whose daughter Polly was kidnapped from her home in Petaluma in 1993 and later found dead. He said the new system is problematic, and said he worries people will opt out.

“It’s an incredibly harsh sound, and it provides you with almost no information,” he said. “That’s not going to help anybody. I think the intention is good, but the application itself is pretty awful.”

The system even interrupted a comedy show in Huntington Beach on Monday night. While a comic was on stage, his routine was interrupted when an audience member got an alert — on a silenced cellphone. The comic stopped his bit, turned to the audience member and asked if he had a tiny ambulance in his pocket.

“People laughed when he called it out because we didn’t really know what was going on,” said Allison Sciulla, 24, a writer and comic who had performed at the show. Sciulla said that no one wants to be “that token dude who didn’t silence his cellphone” at a show. But she said the rules get thrown out the window when a child is missing.

“The fact that it’s an Amber Alert, I just feel like, you know, you get a free pass,” she said. “Someone’s in trouble.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.