Bobby Fischer dies at 64; reclusive genius of the chess board

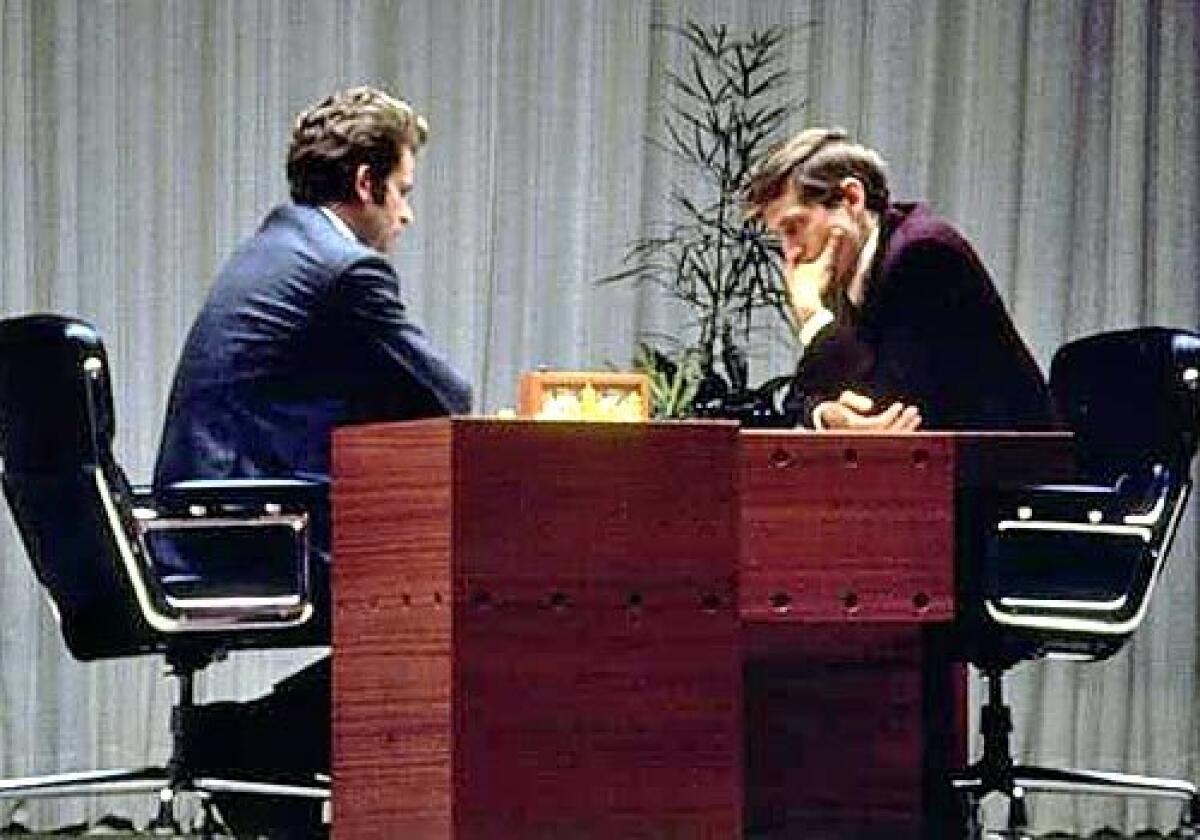

Bobby Fischer, the enigmatic American chess genius who became a Cold War hero with his 1972 defeat of Soviet champion Boris Spassky but fell from grace in later decades when he became a recluse and fugitive known for his hate-filled rants, has died. He was 64.

The legendary chess champion died Thursday in Reykjavik, Iceland, after a long illness, according to his spokesman, Gardar Sverrisson.

FOR THE RECORD:

Fischer obituary: The obituary of chess champion Bobby Fischer in Saturday’s Section A said he withdrew from international competition for five years in 1962. He participated by telegraph in a tournament held in Cuba in 1965. —

Fischer had lived in Iceland since 2005, when that country, which had hosted his legendary match against Spassky, offered him citizenship. He had been on the run from U.S. authorities since a 1992 rematch with Spassky in Yugoslavia that violated economic sanctions against Slobodan Milosevic’s Serbian government. When Fischer made anti-American statements after the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington, the U.S. revoked his passport and unsuccessfully sought his return.

Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, president of the World Chess Federation, called Fischer “a phenomenon and an epoch in chess history, and an intellectual giant I would rank next to Newton and Einstein.”

Once described by biographer Frank Brady as “the pride and sorrow of American chess,” Fischer enjoyed mythical status in the chess world despite turning his back on it for two decades after becoming the world champion at 29. Fischer spent the 1970s and ‘80s living in isolation in Pasadena and Los Angeles, turning down lucrative offers to display his formidable talents against competitors eager to face him across a checkered board.

Even in his strange exile from the chess scene, however, Fischer continued to haunt it. He became the Howard Hughes of chess, with fans eager for his return reporting sightings at tournaments and continuing to analyze his games years after other champions had taken his place.

He had transformed the humble game, his encounter with Spassky making front-page news and causing sales of chess sets and memberships in chess clubs to skyrocket.

“It was Bobby Fischer who had, single-handedly, made the world recognize that chess on its highest level was as competitive as football, as thrilling as a duel to the death, as aesthetically satisfying as a fine work of art, as intellectually demanding as any form of human activity,” Harold C. Schonberg wrote in “Grandmasters of Chess,” published in 1973. “If for no other reason, Bobby Fischer was and would be the greatest chess champion who ever lived.”

Born in Chicago on March 9, 1943, he barely knew his father, a German physicist who divorced his mother when he was 2. His mother raised him and an older sister, Joan, on her own. A schoolteacher and nurse who later became a physician, Regina Wender Fischer spent long hours at work and saw little of her children when they were growing up.

In 1949, she moved her family to New York, where Bobby attended a progressive private school on a scholarship. About this time, when he was 6, Bobby’s sister gave him a chess set and he began to learn the game.

When, within a short while, it became an obsession, he said, “All I want to do, ever, is play chess.”

By the time he was 8, he was playing matches at Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village under the tutelage of Carmine Nigro, president of the Brooklyn Chess Club. He soon moved on to higher-level playing at the Manhattan Chess Club. In 1956, when he was 13, he became the youngest winner of the U.S. Junior Championship. In 1958, he stunned the American chess world by winning the U.S. championship, which qualified him to play in the Interzonal Tournament in Portoroz, Yugoslavia. He became the youngest international grandmaster in the history of the game.

In 1959, he captured the U.S. title again and dropped out of Brooklyn’s Erasmus Hall High School. Living alone in Brooklyn after his mother remarried and moved to England and his sister left New York, Fischer devoted himself to chess and continued to rack up impressive wins. Between 1958 and 1967, he won eight of the 10 U.S. championships.

He also moved up in international play, finishing second at the International Tournament in Bled, Yugoslavia, in 1961, and taking the title at the Interzonal Tournament in Stockholm in 1962.

He stumbled badly at the next international event, the Candidates Tournament on the Caribbean island of Curacao in 1962. He finished fourth behind three Soviet competitors. Although observers said Fischer had not played well, the young American alleged that the Soviets had conspired against him. He aired his charges against them in a Sports Illustrated article. He then withdrew from international competition for five years. When the rules governing international chess competitions were later revised along the lines that Fischer had proposed, many experts credited him with instigating the changes.

Although absent from the international circuit, Fischer was a major figure domestically, playing in exhibition matches, such as one in Hollywood in 1964 when he took on 50 players simultaneously. He also continued to amass U.S. victories, including his triumph in the 1964 U.S. Championship in which he racked up 11 wins with no losses or draws. One of those games, against Robert Byrne, is often cited as among his most brilliant. It was certainly one of his most dramatic: He appeared to be losing until he unleashed a final combination of moves in a sudden attack that made Byrne’s position hopeless. Such imagination and verve caused experts to describe him as an artist on a par with world greats such as Brahms, Rembrandt and Shakespeare.

When Fischer returned to international competition in 1970, he did it with flair, winning three major tournaments and the right to face Spassky, the reigning champion, in Reykjavik.

By then, his reputation -- as demanding, unpredictable and surly -- was firmly established. He drove the Reykjavik officials batty, demanding a Mercedes-Benz with an automatic transmission, a swimming pool reserved for his exclusive use and a certain kind of chess table. He even prescribed the distance of the audience from the players.

At one point, while still in New York, he threatened to withdraw, complaining that the prize money was insufficient. Henry Kissinger, then President Nixon’s national security director, called Fischer, urging him to go. James Slater, a London millionaire, doubled the purse to an unprecedented $250,000.

Fischer went to Reykjavik but continued to rile nearly everyone. He walked out of a game when he said the noise from the cameras was distracting. He arrived late at games and kept threatening to pull out.

The match transfixed television audiences around the world whose interest had been fanned by coverage that framed it in political terms. The Soviets had monopolized the world championships since World War II and regarded their domination of the game as evidence of the superiority of the socialist system. Fischer himself portrayed the historic contest as “the free world against the lying, cheating, hypocritical Russians. . . . They always suggest that the world’s leaders should fight it out hand to hand. And that is the kind of thing we are doing . . . over the board.”

There was no lack of drama in the contest. Both players blundered in the beginning, then fought furiously for the upper hand. At one point there were seven draws in a row.

Compared to that thrilling run of draws, the end, on Sept. 1, 1972, after two months of play, was anticlimactic. The players adjourned after five hours of play with Fischer clearly ahead. When it was time to resume play, Fischer sat alone at the table. Spassky, after studying the positions, phoned in his resignation, making Fischer the world champion.

Three years later, Fischer set another record: He became the first world champion to give up his title without losing. After failing to win a change in the rules by which the challenger must win, Fischer refused a challenge from Soviet grandmaster Anatoly Karpov, forcing the International Chess Federation to strip Fischer of his crown.

He avoided competition for two decades. By the time of his forfeiture, he was living in Pasadena, apparently with little means of support. He had joined the Pasadena-based Worldwide Church of God and reportedly gave it $61,000 of his Reykjavik prize money. Disillusioned, he left the church after Jesus Christ failed to return in 1975 as church founder Herbert W. Armstrong had promised.

Odd incidents popped up in the news, such as when Fischer was mistaken for a robber and jailed for two days. He accused Pasadena police of mistreating him and voiced his complaints in a 14-page pamphlet titled, “I Was Tortured in the Pasadena Jailhouse.”

The Los Angeles Times reported in 1983 that he had cut himself off from most of his friends and had spent the previous decade living in cheap apartments, rundown hotels and the basement of a Pasadena home owned by a woman who appeared to be his last remaining friend.

He was lured from seclusion in 1992 by the offer of a $5-million rematch against Spassky in Yugoslavia. He proceeded to play despite a warning from the U.S. government that his participation would violate the economic sanctions imposed on the Milosevic regime. Asked about the possibility of a 10-year prison sentence and $250,000 fine if he played, Fischer stunned reporters at a news conference when he took out the cease-and-desist order from the U.S. Treasury and spat on it.

He won the match, collecting $3.3 million, but spent the next decade as an international vagrant, living in Germany, Hungary, the Philippines and Japan.

He made the news sporadically, often because of offensive remarks he made about Jews. He repeatedly claimed that he was the victim of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy, even though his mother was Jewish.

After the 9/11 attacks, he gave an interview to a Manila radio station in which he pronounced the destruction “wonderful” and said he wanted “to see the U.S. wiped out.”

The U.S. revoked his passport, which led in 2004 to his arrest by Japanese authorities at Tokyo-Narita Airport. He spent eight months in a Japanese jail until Iceland offered him refuge. While he was a fugitive, his mother and sister died, and he was unable to attend their funerals. He has no known survivors.

Over the years, many theories were offered to explain his bizarre behavior. Garry Kasparov, the Russian grandmaster, speculated in the Washington Times in 1990 that Fischer had become “a prisoner of chess who got lost in its depths and could not find his bearings in the real world outside.” Gudmundur Thorarinsson, who organized the 1972 Fischer-Spassky match, told the London Guardian in 2005 that Fischer occupied “a gray area between a genius and someone who is insane,” adding that he did not think Fischer was mad “but he is not like most people.”

What few commentators dispute is the impact he had on chess.

“Suddenly people . . . could turn professional. Prize monies went up. There was talk of founding a professional league. . . . Everybody was playing chess,” David Edmonds, co-author of the book “Bobby Fischer Goes to War,” told National Public Radio a few years ago. “And the very sad fact for chess, not just in America but in Britain and the West and actually all around the world, was that when Bobby Fischer failed to defend his title . . . in 1975, and became an almost complete recluse, his disappearance sucked out much of that boom in chess interest.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.