Tom Steyer gets little payoff for millions spent on green issues

Environmentalists had something in their arsenal for Tuesday’s election they never did before: a billionaire benefactor willing to empty his pockets of tens of millions of dollars to bring climate change to the forefront of political debate and elect candidates committed to fighting global warming.

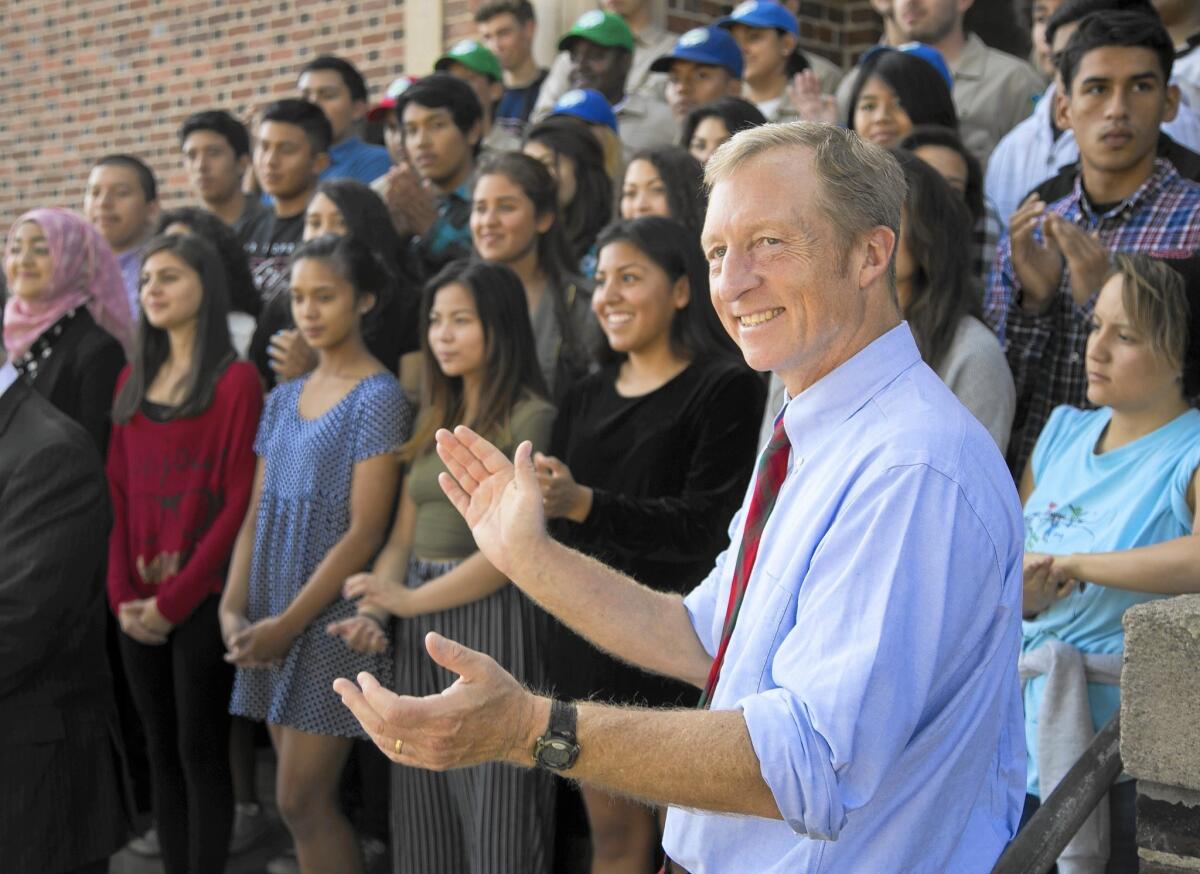

But California hedge fund titan Tom Steyer’s $74-million bet — most of it from his own wallet — yielded little payoff. On Tuesday, voters elected the most hostile Congress environmentalists have faced in years.

The Republicans who won control are already making plans to roll back President Obama’s signature emission reduction efforts, green-light the controversial Keystone XL pipeline that would transport Canadian tar sands oil to the U.S. Gulf Coast, and cancel subsidies for renewable energy.

Steyer says he has no regrets.

“I feel great,” he said by phone from his organization’s San Francisco office. “We set out to put climate on the ballot in a bunch of states, to build an organization and to build a relationship with a bunch of voters.”

He argued that all of that happened, pointing to hundreds of thousands of climate-minded voters newly enlisted in his organization, NextGen Climate, the emergence of global warming in the debate in several races, and the retreat by various GOP candidates from a platform of outright denial of climate science.

He chalked up Tuesday’s results to “that part of the world we don’t control.” Steyer said there was no approach that would have overcome the Republican tide that gave the party control of Congress and defeated several of the candidates NextGen backed.

But the election results raise new questions about the approach deep-pocketed, green-minded donors are taking toward electoral politics. Despite their best efforts, and the huge amount of money invested, they are failing to get voters to set aside other concerns and cast their ballots on environmental issues. This time out, the president’s record and the economy were the forefront issues, with all others receding.

“The take-away here is this was not a successful strategy,” said Josh Freed, vice president for clean energy at Third Way, a group that seeks a middle path between the two warring parties. “Candidate positions on climate do not move the overwhelming majority of voters to pull the lever for or against them. I hope these organizations take a step back and come up with a different approach.”

Steyer’s group saw its candidates victorious in U.S. Senate races in Michigan and New Hampshire, and in state legislative races, including in Oregon. But candidates they backed lost in hotly contested Senate races in Colorado and Iowa. NextGen also failed to unseat the governors of Florida and Maine, targeted by the organization for their outspoken skepticism of climate science.

The unpopular GOP governor of Pennsylvania, Tom Corbett, which Steyer’s group campaigned against, lost. But even in that race — won by NextGen’s candidate, Democrat Tom Wolf — global warming hardly was a factor, according to G. Terry Madonna, who directs the Franklin & Marshall College Poll in Lancaster.

Steyer’s impact was “Zero. None. Zero,” he said. Climate change “was not an issue at all. It has literally no salience with voters. It didn’t ever come up.”

University of New Hampshire pollster Andrew Smith said much the same with regard to the Senate race in his state, which Democratic incumbent Jeanne Shaheen won. “I don’t think anybody paid any attention to global warming this election,” he said.

In part that is because much of Steyer’s money was spent airing ads on issues his organization thought were more likely to turn out the Democratic faithful. But that too sometimes backfired.

In Colorado, independent pollster Floyd Ciruli suggested Steyer’s heavy TV advertising, which seized on a Democratic theme emphasizing abortion rights, may have actually hurt Democratic Sen. Mark Udall, who lost to GOP Rep. Cory Gardner.

“It was probably a net negative,” Ciruli said. “It turned out to be one of those things that threw Udall on the defensive. He was being parodied and mocked for it and criticized for it.”

Even Steyer’s strategists acknowledge that climate change is not a top-tier issue now. The question is whether it ever will be. Advocates such as Freed say the push seems to be futile, and well-funded green political groups should shift their strategy to more narrowly focused efforts with bipartisan appeal. They might start, he said, by being more open to such GOP-favored options as nuclear energy.

The green campaign efforts instead focus on getting Congress back to where it was in 2010, when it almost passed a California-style law that would have capped greenhouse gas emissions nationwide.

NextGen officials say they are confident in their strategy — and persistent. “This is a multi-cycle effort,” said Chris Lehane, Steyer’s lead political strategist. “If it was easy, it already would have been done.... Social change like this is not like switching on a light bulb.”

The GOP takeover of the Senate occurs as the science of climate change has grown more definitive and the predictions of widespread effects more detailed and dire. On Sunday, a panel of hundreds of climate scientists convened by the United Nations warned that climate change driven by the burning of fossil fuels was already affecting life on every continent and in the oceans and that the window was closing rapidly for governments to avert the worst damage expected later this century.

Yet skepticism of climate science remains Republican orthodoxy. North Carolina Sen.-elect Thom Tillis said in a primary debate that climate change is not “a fact.” Sen. James M. Inhofe of Oklahoma, who is expected to take the helm of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, has called climate change “the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people” and dismissed the U.N. science panel “as a front for the environmental left.”

Obama moved to cut greenhouse gas emissions by issuing new rules for power plants and the nation’s vehicle fleet. The GOP-run Congress will not be able to nix the rules outright. But it could so thoroughly weaken or delay them through riders to key legislation that they’d be rendered ineffective, analysts said. Deeper cuts to the nation’s emissions would probably require congressional action, and the current GOP position on climate change makes such action improbable.

Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune acknowledged there was a “copious amount of bad news” in Tuesday’s election. But he says there was “significant good news” as well.

“Candidates who formerly denied climate science are now saying they are not scientists and instead talk about clean energy and associate themselves with it,” he said.

“The money from Tom Steyer made a difference in elevating climate science and pushing all these lawmakers to move off a denial platform,” Brune said.

Halper reported from New Orleans, Barabak from Los Angeles. Times staff writer Neela Banerjee in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.