How the 1981 assassination attempt changed Nancy Reagan

Reporting from WASHINGTON — Nibbling on chicken pot pie with a small group of friends at a private dinner in the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Nancy Reagan kept the conversation light until she turned to the guest on her left, a beloved former Secret Service agent who three decades earlier had saved her husband’s life.

The former first lady began to speak, then suddenly stopped short. Her eyes glistened and her hands trembled. Something in Jerry Parr’s 80-year-old face had brought her back to the painful day when her husband, President Reagan, was nearly killed.

“Jerry,” she said haltingly, “thank you for giving me my life back.”

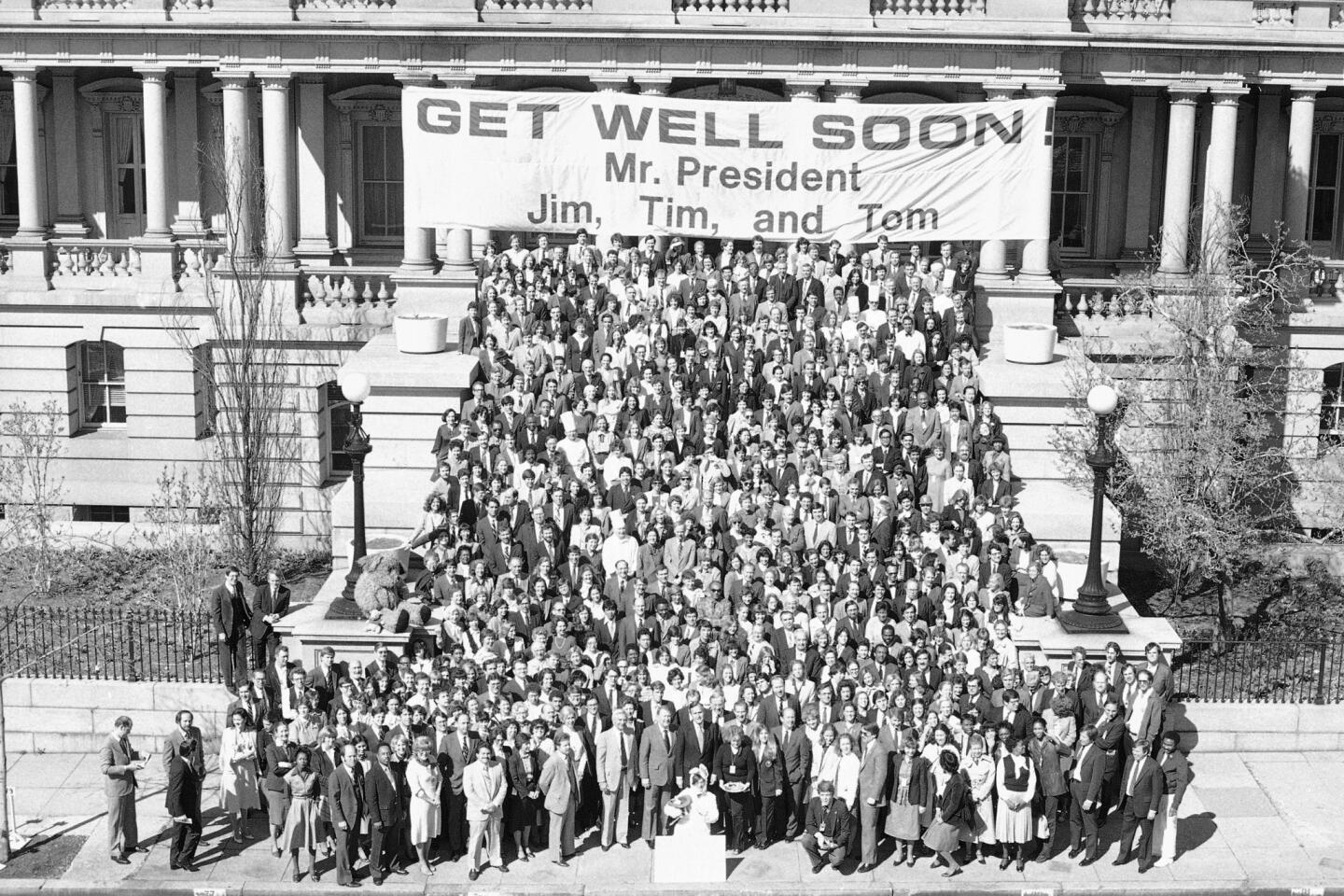

It was clear that night in 2011 that the memory of the assassination attempt on President Reagan remained vivid in the former first lady’s mind, even 2,500 miles distant and thirty years removed from the shooting scene outside a Washington hotel. Friends and former advisors say there was rarely a day that Nancy Reagan didn’t hark back to the trauma of March 30, 1981, an event that recalibrated her husband’s presidency and ultimately played a role in reshaping his legacy, and hers.

Surviving against the odds, Ronald Reagan believed he had been spared for a purpose and somehow put the horror of that day behind him. His wife, on the other hand, had a much harder time letting go of her fears.

She became a bigger worrier, especially when it came to her husband’s safety. But it also marked a turning point, in which she took a more assertive role in expressing her views on matters of security, scheduling and policy, often to the frustration of White House aides.

“The assassination attempt profoundly changed her,” said Craig Shirley, a former Reagan aide and author of “Last Act: The Final Years and Emerging Legacy of Ronald Reagan.”

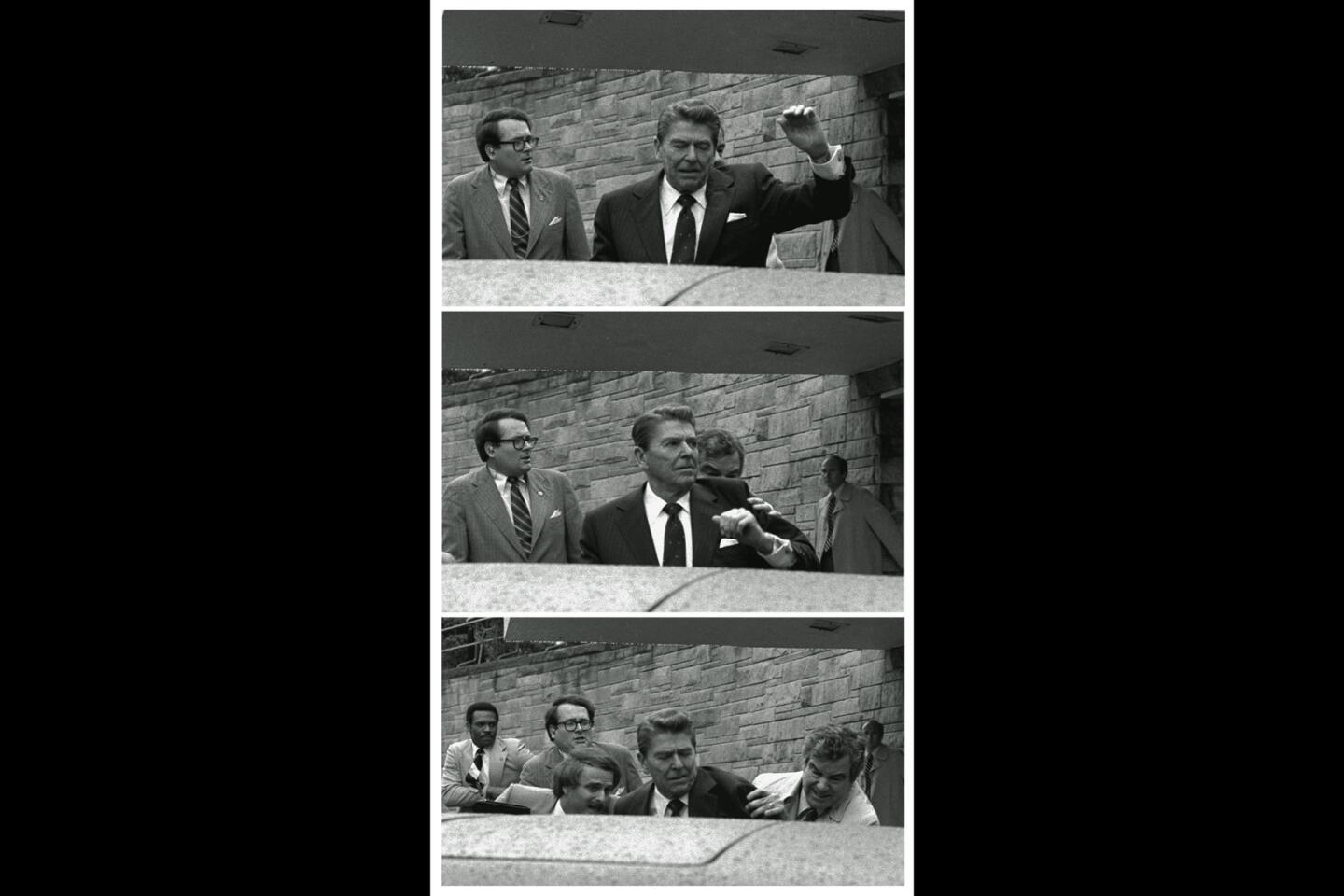

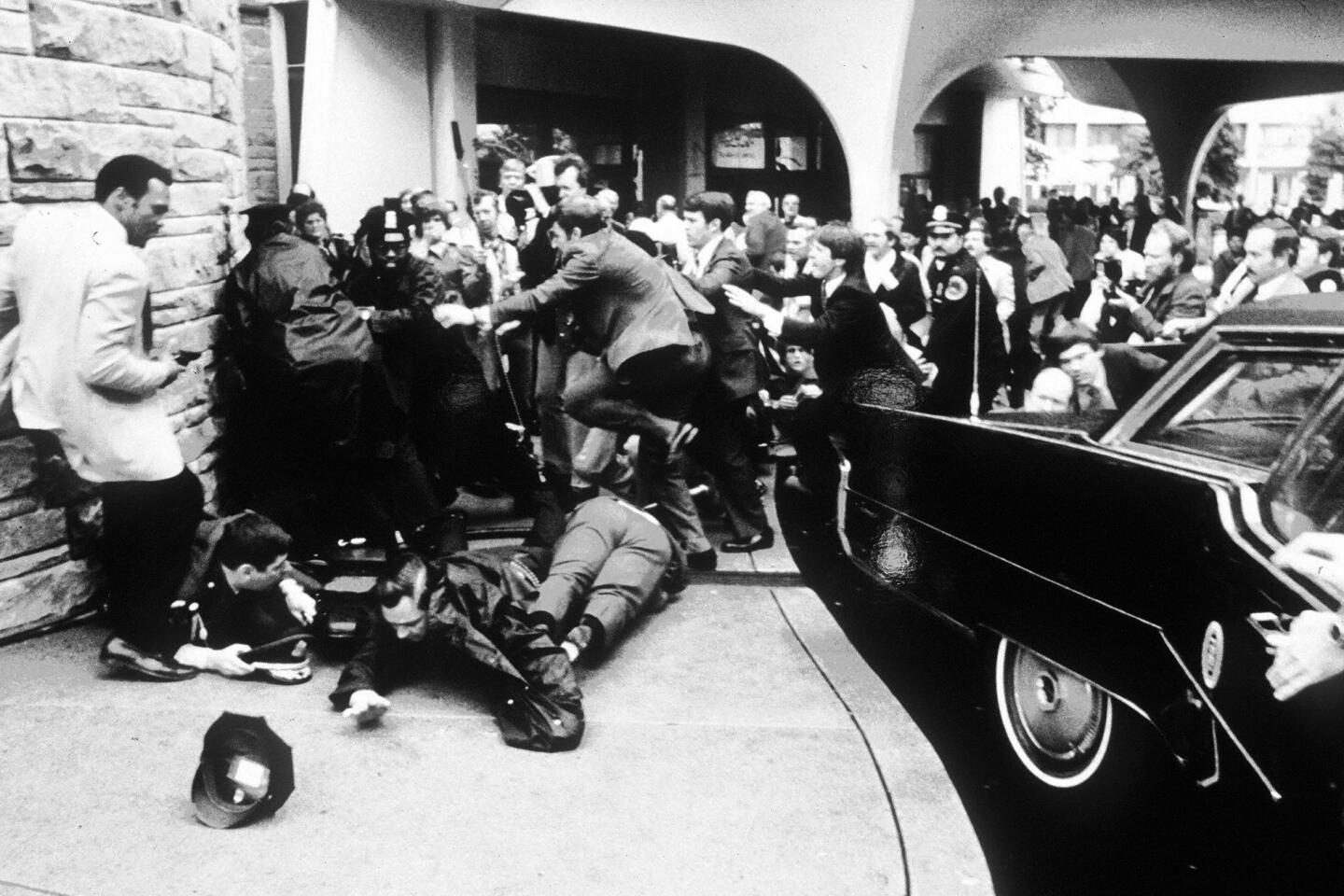

Shirley and other historians have long said that Reagan might not have become president without Nancy Reagan, who died Sunday at the age of 94. As a couple, they shared a powerful emotional connection and strategic partnership in which their traits complemented each other. That bond only deepened after he and three others were shot and wounded after departing a speech at the Washington Hilton.

In the hours before the shooting, Nancy Reagan had attended a luncheon in Georgetown, though she departed early because she felt something was amiss. Not long after she returned to the White House, she was told by a Secret Service agent that there had been a shooting and that her husband was being rushed to George Washington University Hospital.

She raced to the emergency room and immediately demanded to see her husband. “I’ve got to see him,” she told top presidential aide Michael Deaver. “Mike, they don’t know how it is with us. He has to know I’m here!”

In the trauma bay, she found President Reagan on a gurney, a tube draining the blood filling his chest. He was in bad shape — the bullet had lodged an inch from his heart, and he was losing blood at an alarming clip.

Seeking to reassure his frightened wife, Reagan famously quipped: “Honey, I forgot to duck,” borrowing a line that boxer Jack Dempsey supposedly uttered to his wife after he lost the heavyweight championship in 1926.

Doctors rushed the president into surgery, where they removed the bullet and stopped the bleeding (he ended up losing more than half of his blood). Over the next 13 days in the hospital, Nancy Reagan rarely left her husband’s side. The stepdaughter of a Chicago neurosurgeon, Nancy Reagan aggressively questioned doctors about the president’s care, taking the first steps in her more forceful role as first lady.

“She was tough,” said Dr. David Gens, one of the surgeons who treated Reagan and spoke daily with his wife. “We couldn’t throw fluff at her. She asked lots of questions and was prepared. You could tell she was completely devoted to her husband.”

If Nancy Reagan hoped that returning to the White House on April 11 would help calm her nerves, she was disappointed. “How was I ever going to live through eight years of this?” she wrote in her 1992 autobiography, “My Turn.” “Night after night, I lay beside my husband and tried to drive these gruesome thoughts from my mind. Ronnie slept, but I could not.… When you are as frightened as I was, you reach out for help and comfort in any direction you can. I prayed what seemed like all the time, more than I ever had before.”

She began secretly consulting an astrologer, Joan Quigley, a friend whom Nancy Reagan later described in her memoir as a quasi-therapist and good listener.

The first lady, however, was known to drive White House aides to distraction by seeking changes to her husband’s schedule based on the astrologer’s advice. When her relationship with Quigley became public, it caused the first lady chagrin and embarrassment.

“I don’t recall anyone saying, maybe Mrs. Reagan should have some counseling,” said Lou Cannon, a former reporter and historian who wrote the acclaimed biography “President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime.” “She was just expected by everyone to shake it off and go like business as usual. But I think she was deeply traumatized by it, and I don’t blame her for being superstitious and seeking help, even from an astrologer. I think it was completely understandable. She had almost lost her husband and we had almost lost our president.”

As the months wore on, Mrs. Reagan became more involved in the president’s schedule and travel arrangements, as well as more outspoken in expressing her views while advocating for those of her more easygoing husband.

“I think the assassination attempt reminded them that their time was short — in office, in life — and the clock was ticking,” said Ken Khachigian, a former chief White House speechwriter and senior aide. “They didn’t have all the time in the world to do everything they wanted. And she wanted to help make that happen.”

Khachigian also noticed a more subtle change in Nancy Reagan. She often seemed at ease, he said, only when she and her husband were ensconced in safe surroundings.

“The happiest I ever saw her was at Camp David, on Air Force One or at their ranch,” he said. “You can’t get more secure than that. They were entirely and completely sealed and safe. She could be gay and delightful, cheerful, in those places. She was a different person.”

After the Reagans left the White House in 1989, Nancy Reagan remained apprehensive. She often assessed their security and peppered her bodyguards with questions about threats. It was clear to agents that the assassination attempt had cast a long shadow that followed the couple well into retirement.

“She was concerned about security, and she let you know she was concerned about it,” said Stephen T. Colo, a former Secret Service agent who led the former president’s detail from 1992 through 1994. “Listen, if he was getting out of the car, and he bumped his head, she would give you that look.”

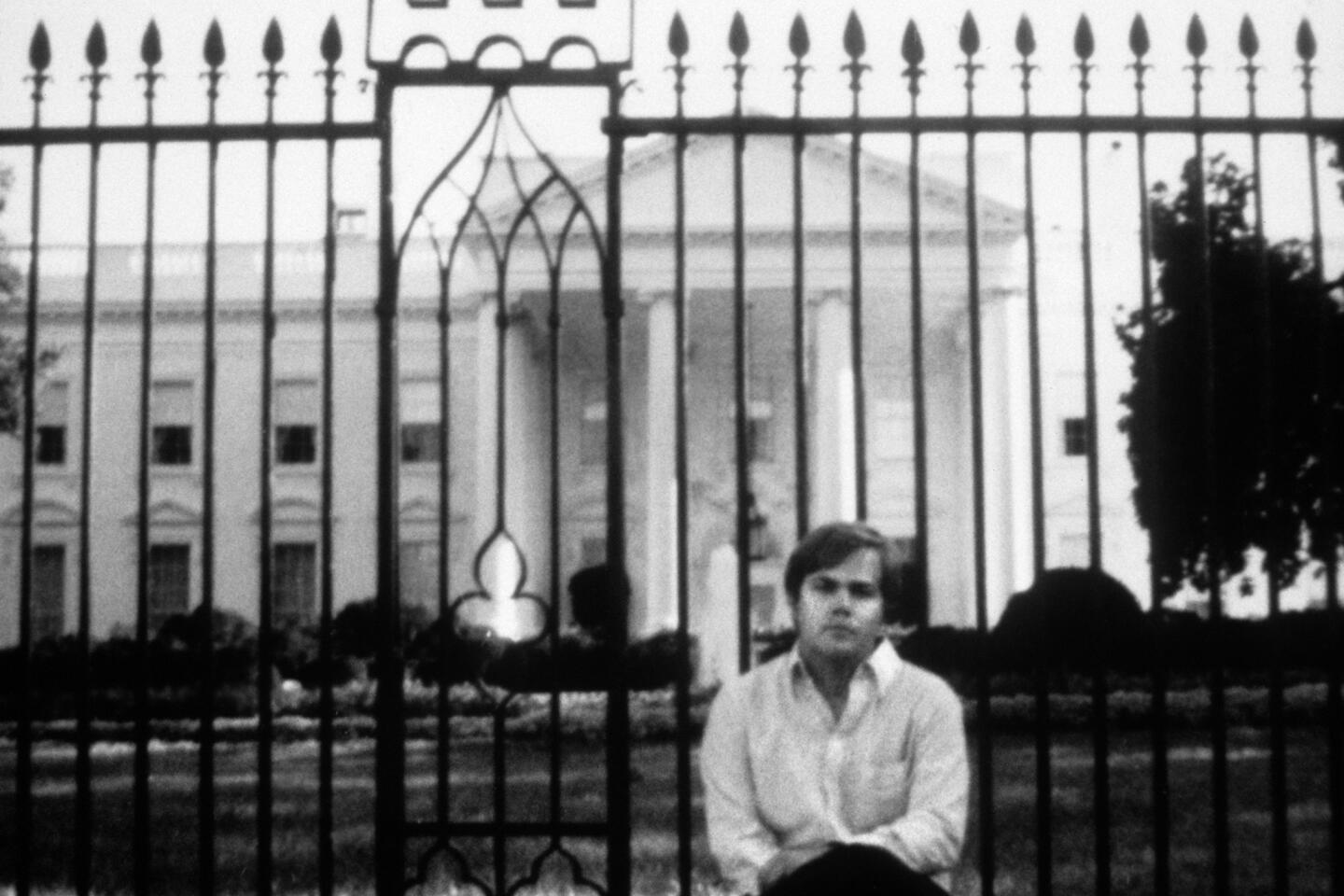

For her part, Nancy Reagan never blamed her bodyguards for allowing John W. Hinckley Jr. to open fire within 15 feet of her husband. She took pains to praise agent Tim McCarthy, who took a bullet for the president, and Parr, who made the life-saving decision to take the president to the hospital, not the White House. Parr died in October.

A couple of years ago, a decade after Ronald Reagan had died from ailments related to Alzheimer’s disease, McCarthy visited the first lady, and the assassination attempt inevitably came up in their conversation.

“She told me, ‘I still remember that day with a chill,’” McCarthy said. “She didn’t forget that until the day she died.”

Times staff writer Del Quentin Wilber is the author of “Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald Reagan.”

MORE ON THE REAGANS

Timeline: The life of Nancy Reagan

From the Archives: Former President Reagan Dies at 93

Nancy Reagan dies in Los Angeles at 94: Former first lady was President Reagan’s closest advisor

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.