Missouri governor orders more National Guard troops to Ferguson

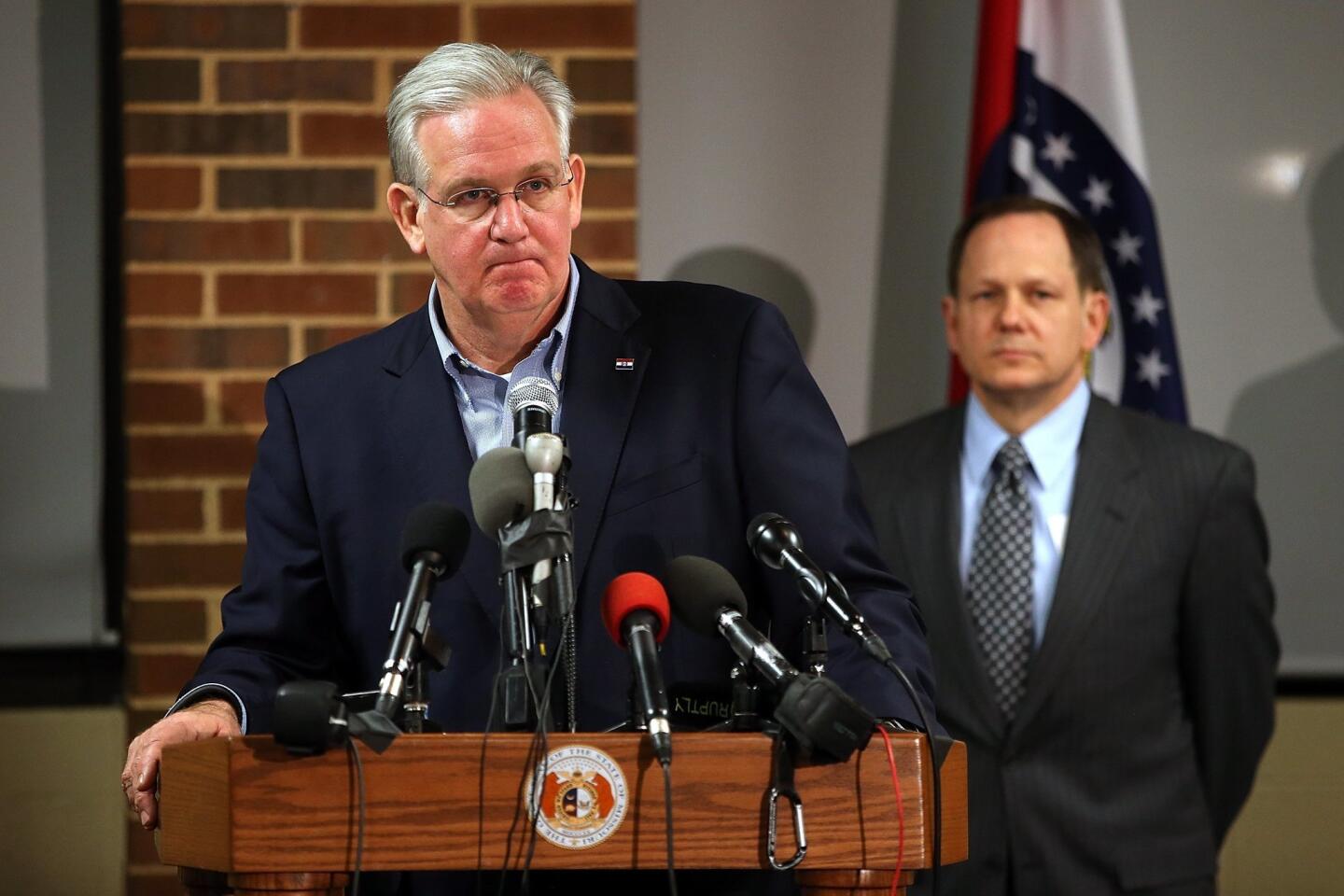

Reporting from Ferguson, Mo. — Amid criticism that he did not effectively deploy the National Guard, Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon on Tuesday said he is sending more troops to the St. Louis region to bolster security after a night of rioting and looting in Ferguson.

Hours after a grand jury decided not to indict Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson in the fatal shooting of unarmed Michael Brown, violence erupted in Ferguson as building burned, gunshots echoed in the air and police responded with tear gas. Dozens were arrested.

“The National Guard was not deployed in enough time to protect all of our citizens,” Ferguson Mayor James Knowles told reporters at an afternoon news conference. “We are asking the governor to deploy the Guard to protect our people.”

Nixon was planning to meet with Guard officials Tuesday, but the governor said he would send additional troops.

“The violence we saw in areas of Ferguson last night is unacceptable,” Nixon said in an email sent to reporters. “That is why today I am meeting with leaders from the Guard and law enforcement to ensure the protection of lives and property.”

Protests continued Tuesday in St. Louis, where a crowd marched near the federal courthouse in downtown St. Louis and overturned barricades while chanting, “You didn’t indict. We shall fight,” the Associated Press reported.

St. Louis County Prosecutor Robert McCulloch’s decision to wait until nightfall to announce the results of a grand jury probe into Brown’s death has been criticized by law enforcement experts and Ferguson activists, who said the move put police at a major tactical disadvantage and offered agitators the cover of darkness.

“Of all the events and all that happened, the single event I am most hard-pressed to explain is why in the world it was announced at the time it was,” said Wayne Fisher, a professor with the Police Institute at Rutgers University in Newark, N.J., and former assistant state attorney general there. “Announcing it in daylight would have given a tactical advantage to law enforcement officers.”

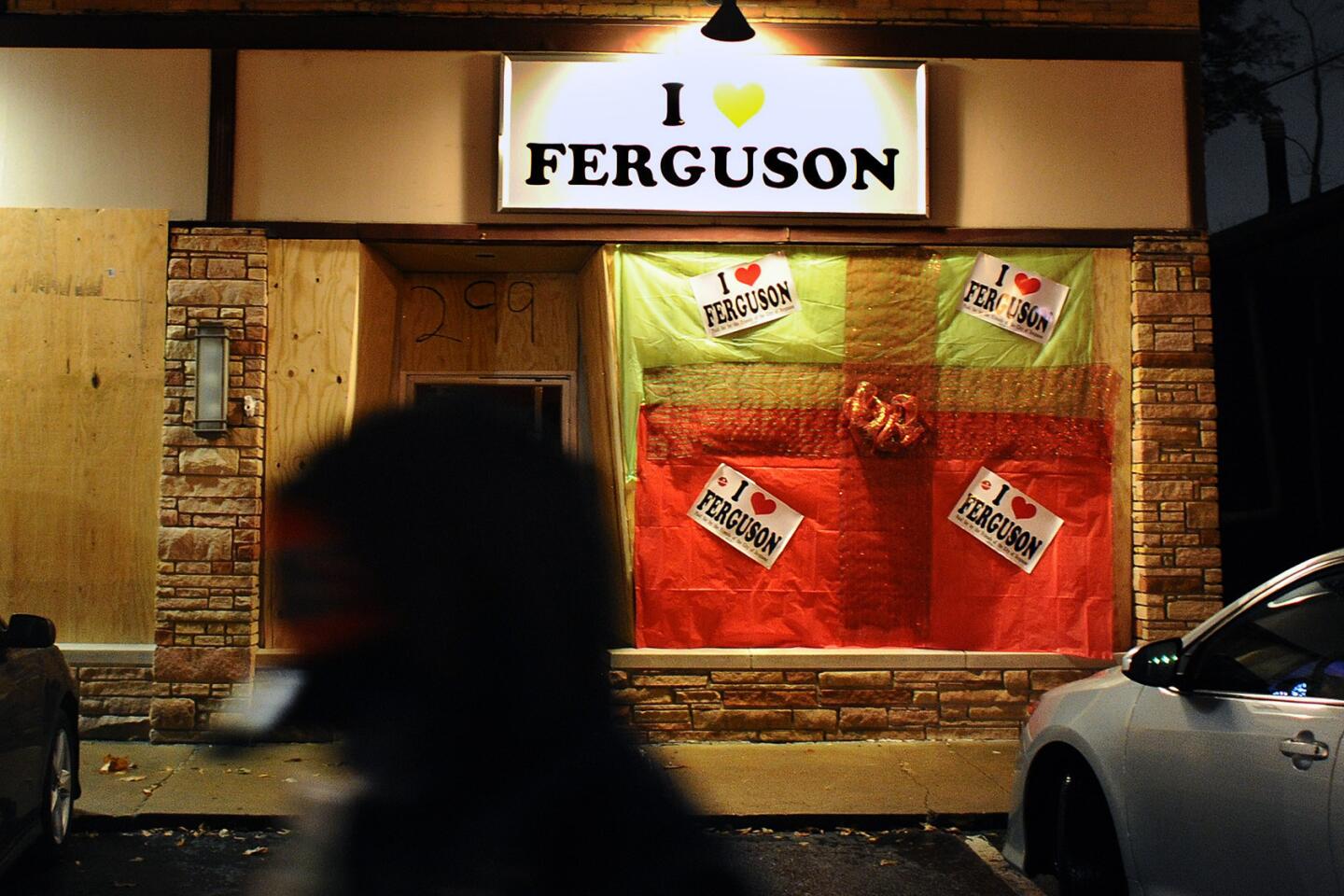

Ferguson was reeling Tuesday from hours of fiery looting overnight.

Attorney Benjamin Crump, who represents the Brown family, lashed out against the grand jury decision, calling the proceedings a “completely unfair process.”

“We object as publicly and loudly as we can,” Crump said. “This process is broken .... We know that our children deserve equal justice.”

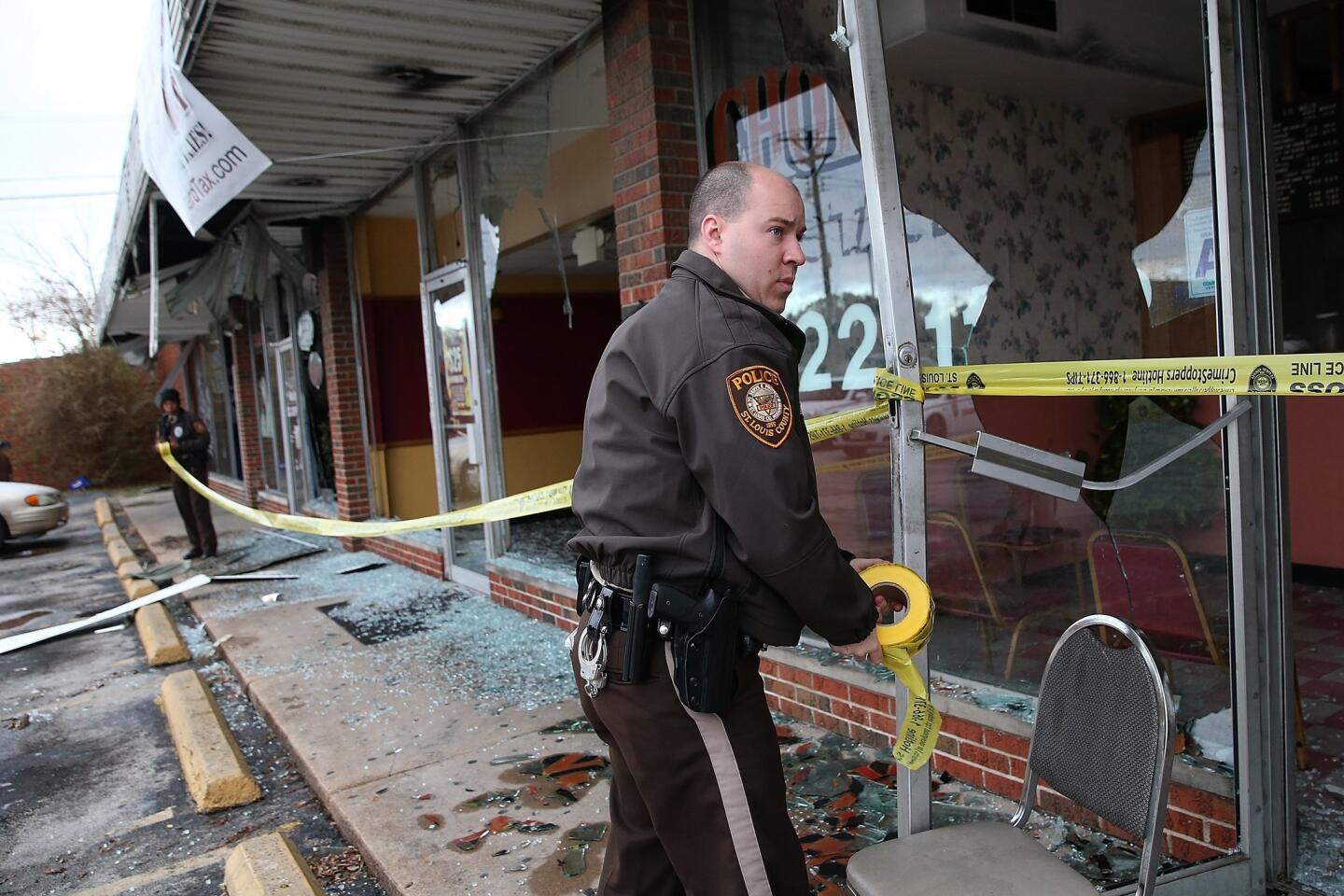

His comments came as the scope of the destruction was clear as wisps of smoke lingered over burned-out buildings and looted businesses. Police checkpoints and yellow tape wrapped around the entrances to West Florissant, blocking the trickle of residents and sightseers who came to see the damage.

At least a dozen buildings were burned and 61 people arrested in Ferguson during the violence that followed a St. Louis County grand jury’s decision not to indict Darren Wilson, a white police officer who fatally shot Michael Brown on Aug. 9, touching off weeks of protests. In addition, 21 more people were arrested in St. Louis, where some windows were broken along South Grand Avenue.

At least 14 people were injured during the overnight protests, including two people who were admitted to Barnes-Jewish Hospital for treatment of undisclosed injuries. That hospital treated and released five people. Six others were treated for minor injuries at Christian Hospital, near Ferguson. Saint Louis University Hospital treated and released another.

“I don’t think we can prevent folks who really are intent on destroying a community,” Jon Belmar, chief of the St. Louis County police, said.

Those arrested will face charges including arson, burglary, possession of stolen property, unlawful possession of a firearm and unlawful assembly, according to the county police department. Only nine of the arrestees were from Ferguson, a St. Louis suburb of about 21,000 people.

“What I’ve seen tonight is probably much worse than the worst night we had in August,” Belmar said.

Officials had called for calm and Brown’s family led a chorus of people including mayors, governors and President Obama, in asking for a peaceful protest to honor the slain man.

“I’m disappointed in this evening .… I didn’t see a lot of peaceful protests out there tonight,” Belmar said.

The Brown shooting became an immediate sore point in Ferguson, where an overwhelmingly white police force protects an predominantly African American population. Witnesses told of Brown trying to surrender with his arms held high, only to be shot by Wilson in a hail of bullets. Some witnesses told the media that Brown had been shot in the back by Wilson.

In announcing the grand jury decision not to charge Wilson, McCulloch said that much of the witness testimony from the community was unreliable and some conflicted with the scientific evidence, such as, for example, that no bullet entry wound was found in Brown’s back. Some witnesses, McCulloch said, changed their stories as the grand jury proceedings went on for weeks.

The grand jury of nine whites and three blacks met on 25 days over three months and heard more than 70 hours of testimony from some 60 witnesses, McCulloch said.

Evidence from three autopsies was presented along with toxicology and weapons reports.

Despite that evidence, many refused to change their minds about the shooting.

“McCulloch got what he wanted,” Marvin Skull, 55, of neighboring Hazelwood, hollered Tuesday morning at the officers manning the checkpoint in Ferguson.

He then joined a small group of area residents standing nearby who were spiritedly debating the investigation of the shooting, as well as the chaos that unfolded a night earlier.

“What affects Ferguson affects me,” Skull explained to the group that had gathered, citing north St. Louis County’s dense and fragmented collection of small suburbs. “You know why I came? I seen some people looting last night, and I saw them drop stuff. So I came to pick it up and take it back.”

Mary Anne Johnson, 62, of Florissant, who had just gotten off her overnight shift as a mail handler at the post office, asked why the police had not prevented the looting and the arson. She asked a reporter how many of the 61 arrested the night before were from Ferguson — just nine — and questioned whether the grand jury decision gave them the “opportunity to do mischief and bad stuff.”

“I don’t think it’s going to be the end,” Johnson said worriedly. “This generation doesn’t care about killing police.”

“It’s not that this generation doesn’t care about killing police, it’s that these police don’t care about killing people,” interjected a woman who identified herself by her first name, Sherrill.

Sherrill, a sixtysomething resident if a Ferguson apartment complex neighboring West Florissant, added of the rioters, “I understand your emotion, but don’t tear up where you live at .... At the end of the day, we’re all a victim. This is sad.”

Nathan Caldwell, 35, of Florissant, said he drove over to see the damage and talk to people on the street, but the police line kept him — and everyone else — out.

“I understand their frustration,” Caldwell said. “Violence is not the answer. But neither is killing someone unarmed.”

During the night, police were pelted with rocks and batteries. Two police cars were set afire and “melted” on West Florissant Avenue, the scene of many protests, and at least a dozen buildings were torched.

Officials said about 150 shots were fired at police, who did not return any fire.

Highway Patrol Capt. Ron Johnson praised law enforcement’s restraint. “The officers did a great job tonight,” he told reporters. “They showed great character.”

The night’s violence dismayed him, Johnson said. “Our community has got to take some responsibility for what happened tonight .… We talk about peaceful protests, and that did not happen tonight.”

Belmar said he looked forward to the arrival of more National Guard troops, which Gov. Jay Nixon ordered Monday night. Belmar defended police preparedness.

“I don’t think we were underprepared,” he said, adding, “I don’t think we can prevent folks who are really intent on destroying a community.”

It doesn’t take long for someone to pour gas on a building, Belmar said. “I didn’t foresee an evening like this,” he said. “I’ll be honest with you.”

Brown’s parents have scheduled a news conference for later Tuesday morning.

Their call for a peaceful demonstration was heeded Tuesday morning as about 100 people blocked traffic in Clayton, where the grand jury had met.

Many were clergy who gathered shortly after sunrise, blocking intersections, singing spirituals. They also observed a 4½-minute moment of silence to mark the 4½ hours that Brown’s body remained on the Ferguson street before it was removed.

Follow @MattDPearce on Twitter for the latest from Ferguson

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.