El Paso and Juarez know what happens when a wall divides two cities

Reporting from El Paso — When men in olive coveralls began to install 18-foot-high corrugated metal fencing on the international border between El Paso and Ciudad Juarez in 2008, Carlos Marentes joined protesters who complained that building the barrier was like cutting off circulation to America’s own limb.

It was no surprise to him when the city on the Mexican side of the border fence began to wither and die. As Juarez descended into years of drug-fueled violence, El Paso thrived, ranking among the safest cities in the U.S.

President Trump’s directive Wednesday for construction of a new border fence between the U.S. and Mexico stirred consternation once again among the residents of these two cities, who are haunted by the last eruption of violence in Mexico, but who also depend on the exchange of labor and commerce that has persisted even with earlier attempts to divide the two cities.

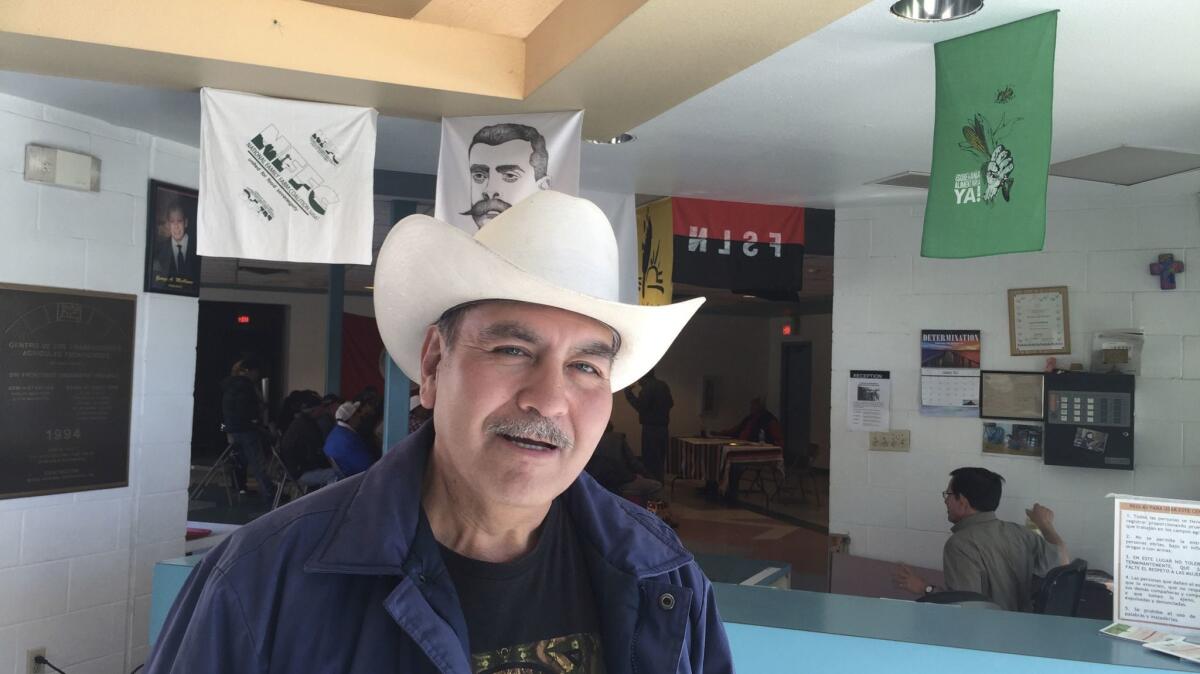

“The fence is a symbol for people who care about national security, not something that actually stops people from crossing,” said Marentes, who runs a center for migrant workers on the U.S. side of the border. Bureaucrats in Washington “don’t know the border,” he said. “It’s a community you can’t separate.”

When U.S. border officials originally fortified the barrier between El Paso and Juarez in 2008, Marentes had predicted it would push undocumented migrant workers to the furthest reaches of the desert to find a place to cross.

His worst fears were realized in the years that followed. Record numbers of migrants from Mexico and Central America died on the arduous trek through the Sonoran Desert into Arizona between 2010 and 2014.

Plans for the original $2.8-billion wall began in 2006, when President Bush authorized construction of a barrier along 650 miles of the border. In some areas it consisted of tall, wire fencing. In Juarez, a project completed in 2008, corrugated metal was sunk six feet into the ground.

Trump has previously said the new wall will be two layers deep, and if it is similar to the highly fortified fencing already in place in Arizona, it will be taller than the 18-to-21-foot-tall fence in El Paso.

The fencing between Juarez and El Paso varies. In most places, it is corrugated metal; in others, a metal mesh. In El Paso’s higher elevations, it’s difficult to tell the fence is there at all.

Marentes worries that plans for a larger wall will push the migrant workers who use his center farther from the relative safety of the cities and into the wild desert of west Texas.

On Wednesday afternoon, 26 migrant workers gathered at the Border Farm Workers Center that Marentes operates in downtown El Paso, across the street from the razor wire of the border fence. They were laid off last year from a chile canning factory when the American company that owned it was sold; some were offered their old jobs back at minimum wage, which they refused.

Since then, most of them have been living off their savings, and on earnings from odd jobs they can find on either side of the border.

On the walls of the center, flags in bold colors feature agricultural worker collectives from Turkey, Indonesia and Brazil.

“The wall needs to come down, and I remember Berlin. It will fall, maybe in 10 years, though,” said Luis Alvarez, 66, who worked in the chile factory and has designs on organizing the laid-off workers into a union.

A larger wall and a more difficult border would complicate those plans, if not scuttle them entirely. Organizing labor here requires buy-in from people on both sides of the fence -- the workers in the U.S. and their families in Mexico.

“People are going to find a way to cross; you cannot stop that,” said Carlos Valdiviezo, 56. “But the wall will change much about life on the border. People will find a way to cross, but it will be more dangerous now.”

Marentes founded the center in 1995 to provide a shelter to migrants who were forced to sleep on sidewalks between bus trips to their shift on farms, part of what he called “El Paso’s hidden.”

The city has successfully managed to separate itself from Juarez’s place as a violent dystopia in the American imagination— even as the Mexican border city has gradually become safer. El Paso has long enjoyed a relatively low violent crime rate, in part because of the buildup of federal law enforcement in the region.

But even businesses that draw almost exclusively from the U.S. side of the border are concerned about the long-term impact of a more restrictive barrier, both in physical infrastructure and the resulting social divide between the El Paso and Juarez.

Leo A. Duran’s family has owned L&J Cafe since his grandfather founded it in 1928 on the edge of a small hill one mile from the Mexican border.

“We are asking for continued social problems, continued violence, with more separation,” Duran said. “I won’t suffer financially, no. But our community as a whole will suffer.”

More than 2.5 million people make up the Juarez-El Paso-Las Cruces, N.M., metro area, which labels itself the largest binational region in the world.

The border region here is indivisible, Duran said. El Paso’s downtown is staffed by workers who walk across the border every morning. Students from Juarez receive in-state tuition at the University of Texas-El Paso.

“You cannot cut off one side of a city and expect it to survive,” Duran said.

Marentes believes the wall allows El Paso to ignore the deep trouble on the other side of the border.

“Juarez is the backyard and dumping ground for our problems,” Marentes said. “It will be even more when you can see it even less.”

Follow @nigelduara on Twitter

ALSO

Trump orders moves on border wall and ‘sanctuary cities’ and is considering a refugee ban

Fresno mayor vows his town won’t become ‘sanctuary city,’ bucking California trend

California ‘sanctuary cities’ vow to stand firm despite Trump threats of funding cutoff

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.