Will Paris climate accord and other environmental pacts survive a Trump presidency?

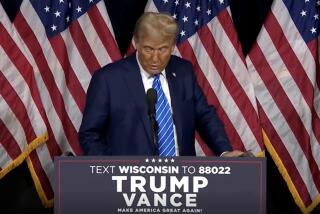

Reporting from SEATTLE — When Donald Trump takes the oath of office in January, he appears poised to become the only world leader who questions whether climate change is real.

The Republican president-elect has called climate change a hoax and said he would “cancel” the United States’ participation in the historic Paris climate accord to reduce carbon emissions. Among the people he is said to be considering to lead the Environmental Protection Agency, which Trump once proposed gutting, is Myron Ebell, a prominent skeptic of climate science.

For the record:

4:41 a.m. Nov. 7, 2024An earlier version of this article described Science Debate as a website that promotes science education for children. Science Debate describes itself as a nonpartisan initiative of American scientists and engineers that promotes political debate on environmental issues, among others.

Trump has also said he would revive the coal industry, expand fossil fuel development, relax restrictions on energy production on public land and do away with the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, which would reduce emissions from power plants. The Republican-controlled Congress that Trump will be working with shares many of his goals.

Now, less than a year after the Obama administration built alliances with China, India and other countries to lead the world in approving the Paris accord, Trump’s victory has given him the power to do much of what he said he wants to do. That has raised profound questions about domestic and international efforts to fight climate change at a moment when scientists say there is no time for delay.

“Millions of Americans voted for a coal-loving climate denier willing to condemn people around the globe to poverty, famine and death from climate change,” Benjamin Schreiber, the climate and energy director for Friends of the Earth, said in one of the blizzard of reaction statements distributed by anguished environmental groups. “It seems undeniable that the United States will become a rogue state on climate change.”

Given Trump’s shifting positions on the campaign trail and uncertainty over who might advise him, it is unclear how actively he will follow through on statements he made about energy and environmental policy. But there was widespread concern among activists and experts that he would roll back President Obama’s policies, be they programs to reduce methane emissions or raise vehicle mileage standards.

“Because they were done with existing authority, not through Congress, it’s easier for another administration that has another view to roll all those things back and I worry a lot that that’s what’s about to happen,” Jason Bordoff, the director of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and a former energy advisor to Obama.

The extraordinary speed at which the Paris accord was enacted into law was driven in part by concerns among world leaders that Trump, if elected, could prevent the U.S. from participating. The U.S. is the world’s second-largest emitter, after China.

On Wednesday, at this year’s United Nations climate conference, in Marrakech, Morocco, world leaders woke to news of Trump’s victory and vowed both to work with the new president and hold his administration accountable.

After congratulating Trump, Salaheddine Mezouar, the president of the conference, said all parties to the agreement “have the shared responsibility to continue the great progress achieved to date.” Mezouar said that he was “convinced that all parties will respect their commitments and stay the course in this collective effort” and that his office would work “in a spirit of inclusiveness and determination, particularly with the new American administration.”

A Trump administration may not be able to formally withdraw from the accord. But because the accord includes no legally binding emissions goals, only the commitment to pursue them and regularly consider strengthening them, Trump could simply choose to ignore it.

California Gov. Jerry Brown insisted Thursday that the state would “stay true” to its commitments on climate change.

“With the deep divisions in our country, it is incumbent on all of us — especially the new leadership in Washington — to take steps that heal those divisions, not deepen them,” Brown said in a statement.

“There’s not much the international community can do about it other than shame and bad will in global diplomacy,” Bordoff said. “And I’m not sure how much that administration would care about that.”

Bordoff noted that Trump is expected to appoint a conservative justice to the Supreme Court, increasing the chances that the court would side against environmental groups and with industry, including on Obama’s Clean Power Plan, which is facing legal challenges.

Trump has said he also supports expanding renewable energy. In comments published in September on the website of Science Debate, a nonpartisan science initiative promoting political debate on scientific issues, Trump wrote, “There is still much that needs to be investigated in the field of ‘climate change.’”

After mentioning the importance of clean water and fighting disease, without linking those issues directly to climate concerns, he continued, “Perhaps we should be focused on developing energy sources and power production that alleviates the need for dependence on fossil fuels.”

Many activists have long argued that government cannot be counted on to lead on climate issues. Some say a blend of global market forces affecting fossil fuels, the declining cost of solar and wind energy, grass-roots activism, legal action in U.S. courts and international pressure could help counter whatever efforts a Trump administration might make to undo existing policies.

“This is obviously a setback, in part because we started so damn late and there’s already quite a bit of damage, but this transition is underway and it’s driven by a whole lot of things — human will, local policy, state policy, international policy, technology development,” K.C. Golden, the chairman of 350.org, said in an interview.

“There will be more of a price to pay and more climate damage will accumulate and be inflicted on people, because we’ll go slower than we would go if we had concerted American leadership. But the lack of American leadership won’t stop the transition.”

Others, worried about the unknown, called on Obama to take further executive action to protect the environment before leaving office.

The Standing Rock Sioux Indian tribe, which has been leading protests against the controversial Dakota Access pipeline, called again on the president Wednesday to withhold a final permit the pipeline’s builder needs to complete it. The tribe worries that the pipeline, whose route would travel just north of its reservation, threatens sacred sites and its water supply.

“In this time of uncertainty,” Standing Rock Sioux Chairman Dave Archambault II wrote, “President Obama still has the power to give our children hope.”

ALSO

In wake of Trump’s win, even some in Silicon Valley wonder if Facebook has grown too influential

Now Trump has his chance to change Washington. But it might change him instead

That glass ceiling? It turned out to be a concrete wall.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.