St. Louis gave minimum-wage workers a raise. On Monday, it was taken away

Ontario Pope has long struggled to stretch his McDonald’s paycheck to cover the basics and provide for his four young children.

But even after more than nine years with the fast-food chain, the 31-year-old St. Louis man said he still lived with relatives or in motels, the fear of becoming homeless never far from his thoughts.

Pope was hopeful when the city passed an ordinance in May that raised the minimum wage from the state’s $7.70 to $10. Finally, he thought, he would be able to save enough money to get his own place and buy simple things for his children.

Now that hope is slipping away.

On Monday, McDonald’s rolled Pope’s wages back to $7.70. He’s one of more than 30,000 workers in St. Louis who could see their wages cut after a state law was adopted prohibiting cities from setting higher minimum wages than the state. The law went into effect Monday.

St. Louis is not the first city to see its minimum-wage ordinances undercut by state legislatures. The issue is a divisive topic across America, and there are 25 states that have minimum-wage preemption laws — when state governments approve laws that prevent local governments from passing such measures — including Kentucky and Iowa, according to Paul Sonn, general counsel with the National Employment Law Group.

But St. Louis is among the few cities where wages have been rolled back.

The city ordinance that raised the minimum wage to $10 took effect in May after nearly two years of legal battles, including a trip to the Missouri Supreme Court, which ruled that the local minimum wage could take effect.

More than 30,000 people in St. Louis saw their wages jump to $10 an hour, a relief for many low-wage workers who struggled to make ends meet.

One of those people who saw her wages shrink on Monday was Wanda Rogers, a 46-year-old cook at McDonald’s.

Rogers, a grandmother and mother of four, has made $14,700 in the year that she has worked at McDonald’s. She said the minimum-wage increase was helping her get on her feet, but news that her employer would decrease her wages was deflating.

“I was in the process of losing my home and just beginning to catch up on my rent,” Rogers said. “It’s going to be a struggle for me again.”

When Missouri’s high court cleared the way for St. Louis to raise the minimum wage, Republicans backed by big business lobbyists quickly passed a bill that created a standard statewide minimum wage that barred cities from having a higher minimum wage than the state.

Proponents of setting a statewide minimum wage argue that doing so will help the economy and help save jobs by insuring uniformity. Having different wages across the state, they argue, could result in layoffs, businesses hiring fewer workers or even forcing businesses to flee the city.

Critics of the bill argue that multimillion-dollar corporations, such as retailers and fast-food chains, can afford higher wages for workers, especially if small businesses decide not to lower the minimum wage for their workers.

And labor groups worry that cutting wages will hurt already-struggling workers and ties the hands of local politicians.

“If small businesses can keep the $10 minimum wage, then big corporations can definitely pay that to their workers,” Rogers said.

Rogers said she lived in low-income housing in downtown St. Louis with seven relatives. “I wish somebody at the top could come and see how hard we work and whether they can support their families off $7.70 an hour.”

Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens backed the rollback bill and said the minimum-wage ordinance passed by politicians in St. Louis would hurt the people it claimed to help.

“This increase in the minimum wage might read pretty on paper, but it doesn’t work in practice,” Greitens said in a June 30 statement. “Government imposes an arbitrary wage, and small businesses either have to cut people’s hours or let them go.... Politicians in the Legislature could’ve come up with a timely solution to this problem. Instead, they dragged their feet for months. Now, because of their failures, we have different wages across the state.”

The law took effect without Greiten’s signature. “I disapprove of the way politicians handled this. That’s why I won’t be signing my name to their bill.”

While businesses in St. Louis are not bound to follow the state’s preemption law on minimum wage, large corporate businesses, such as the fast-food industry, have opted to trim wages.

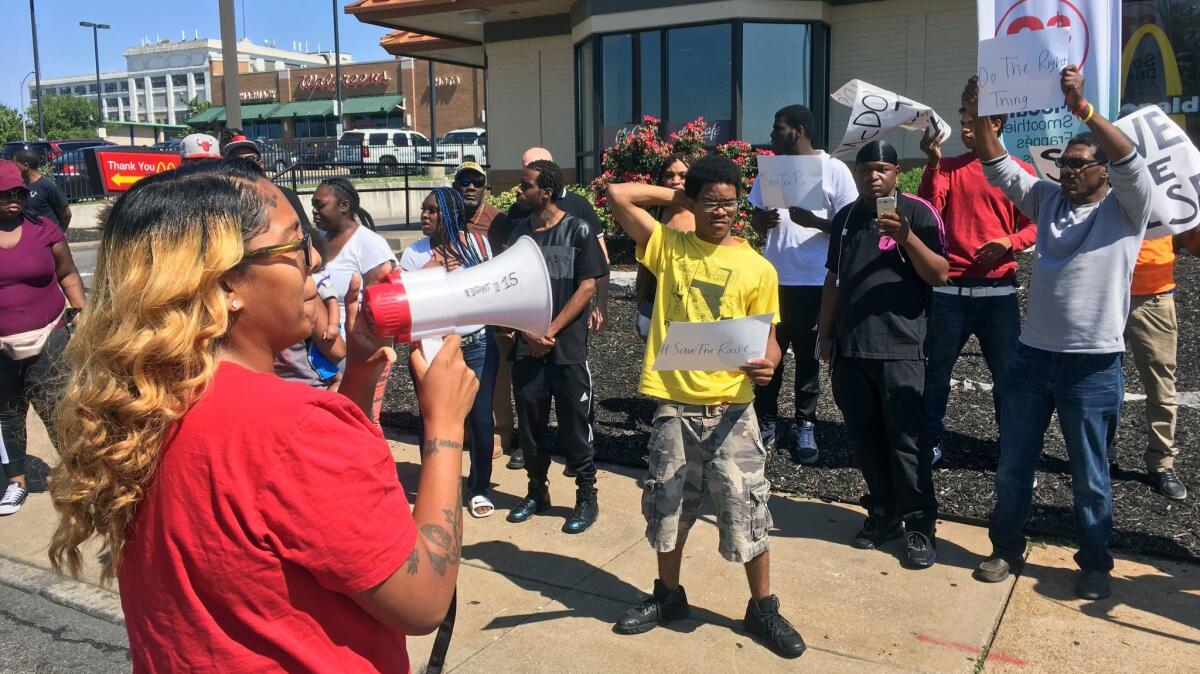

The move prompted local labor groups and activists to start a campaign called “Save the Raise,” which urges businesses to maintain the $10 minimum despite the new state law.

More than 100 small businesses have pledged not to cut paychecks, and 16 members of the St. Louis Board of Aldermen endorsed the campaign.

Ben Poremba, a chef in St. Louis, owns four restaurants that employ about 90 people. He’s one of the small businesses that have pledged to keep the minimum wage at $10.

The decision was easy, he said.

“The cost of living is rising, but not the pay, so it’s morally important not to lower the minimum wage,” he said. “I want to debunk the notion that it’s not good for business, and if smaller businesses can afford it, then big retailers and fast-food companies can as well.”

The new state law also prevents Kansas City, Mo., from increasing its minimum wage to $10. A majority of voters in Kansas City voted Aug. 8 to increase the minimum wage.

Follow me on Twitter @melissaetehad

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.