Chief Justice Roberts’ record isn’t conservative enough for some activists

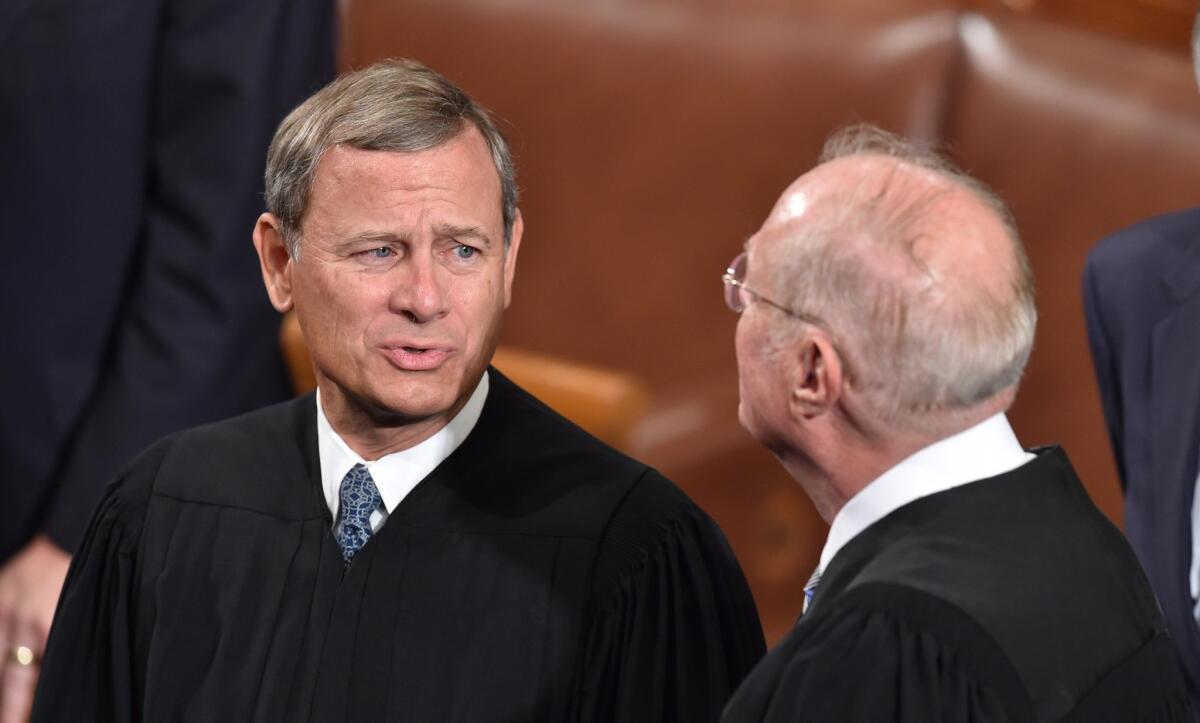

Chief Justice John Roberts and other members of the U.S. Supreme Court arrives before Pope Francis addresses the joint session of Congress on Sept. 24 in Washington, DC.

Reporting from Washington — When a divided Supreme Court handed down six major rulings in the last week of June, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. came down firmly on the conservative side in five of them.

He voted against gay marriage, in favor of weakening a federal law against racial bias in housing and for the Arizona Republicans who challenged the state’s independent panel that draws election districts. He joined 5-4 majorities to block an Obama administration clean-air rule and to uphold a state’s use of substitute drugs to carry out lethal injections.

But as Roberts this week marks the 10th anniversary of becoming chief justice, he finds himself in the crosshairs of right-leaning pundits and GOP presidential hopefuls who brand him a disappointment and openly question his conservative credentials because of the one case of the six in which he voted with the court’s liberals. The decision marked the second time Roberts had voted to uphold President Obama’s healthcare law.

In the recent GOP presidential debate at the Reagan library, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) said it had been a “mistake” for President George W. Bush to have appointed Roberts, a former Reagan White House lawyer who, like Cruz, came to Washington to work as a law clerk for then-Justice William H. Rehnquist. When Roberts was chosen in 2005 to succeed Rehnquist as chief justice, Cruz had lauded him as a “principled conservative.”

In the same debate, Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor and rival presidential candidate, stopped short of saying his brother made a mistake, but he pledged to do better if he were elected president.

“We need to make sure we have justices with a proven experienced record” so they “won’t veer off,” Bush said.

NEWSLETTER: Get the best from our political teams delivered daily >>

Meanwhile, the Judicial Crisis Network, a small conservative group, began an ad campaign this month saying, “We can’t afford more surprises,” and featuring photos of Roberts along with Justice Anthony M. Kennedy and retired Justice David H. Souter, two Republican appointees whose decisions deeply disappointed and angered conservatives.

The Roberts backlash is all the more curious because unlike Souter and Kennedy, the chief justice has not taken what most legal analysts would view as liberal stands. Roberts “is a very conservative justice who occasionally surprises,” said Brianne Gorod, a former court clerk who analyzed his 10-year record for Constitutional Accountability Center, a progressive legal group.

Under his leadership, the court has freed corporations, unions and the wealthy to spend unlimited sums on campaign ads, including through so-called super PACs. His opinion for a 5-4 majority struck down part of the Voting Rights Act, freeing Republican lawmakers across the South to adopt new, tighter restrictions on voting.

Thanks to his votes, the court also has cut back on school integration, upheld gun rights, shielded corporations from class-action lawsuits and ruled in the Hobby Lobby case that company owners have a religious liberties right to refuse to pay for government-mandated contraception benefits for their female employees.

When Kennedy joined with the liberals to rule that Guantanamo prisoners may file court appeals and that greenhouse gases could be regulated under the Clean Air Act, Roberts dissented.

Those stands have not been enough, however, to win Roberts steady plaudits from conservatives. Heading into an election year, the attacks on Roberts appear to reflect shifting views on the right about the court and the proper role for the justices.

From the time of Ronald Reagan through George W. Bush, Republican presidents said they wanted restrained justices who would not “legislate from the bench” and who would uphold the measures adopted by elected lawmakers. This posture of “judicial restraint” stood in contrast to the “activists” — mostly liberals, they said — who gladly struck down laws they did not like.

Roberts promised to be that kind of modest, restrained justice, one who saw his role as akin to a nonpartisan “umpire who calls the balls and strikes.”

Judges have a “limited” role, he told senators during his confirmation hearing. “They don’t make the law. They don’t shape the policy.”

Now, by contrast, libertarians and some other conservatives say the justices should be more aggressive and assertive in protecting property rights and reining in big government.

As chief justice, Roberts has made an effort to show he is an independent judge, not a conservative champion. He has, for example, kept his distance from the influential Federalist Society. While Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr. speak regularly before the conservative lawyers’ group, Roberts has not.

In the last week of June, his instinct for independence and judicial restraint was on display. He was the only justice among the nine who voted both to uphold Obama’s healthcare law and to uphold the state laws that limited marriage to a man and a woman.

The key moment of his tenure so far came in spring 2012. Until then, he had not stood alone with the four liberal justices in a significant case. But he was forced to choose between his fellow conservatives and his commitment to judicial restraint.

Kennedy, Scalia, Thomas and Alito were prepared to strike down entirely the Affordable Care Act that had been passed by Congress under Democratic control and signed by a Democratic president. Had Roberts joined them, the election-year ruling would have been seen as a dramatic example of judicial activism by five Republican appointees vetoing a law championed by Democrats.

Roberts found a narrow way to uphold the healthcare law on the grounds that Congress had the power to impose a tax penalty on middle-income people who refused to buy health insurance. At the same time, he said the Republican-led states could refuse to expand their Medicaid programs for the poor.

That same month, he joined with Kennedy and the court’s liberals to block most of an Arizona law that targeted immigrants living there illegally. Roberts agreed that federal authorities, not the states, had control over immigration policy.

Since then, Gorod says there has been some shift in Roberts’ votes and opinions. “He now occasionally breaks company with his conservative colleagues,” she said. “He is concerned about the reputation and legitimacy of the court. He’s also concerned about increasing partisanship in Washington. This doesn’t mean he is becoming a liberal.”

This year, when the chief justice rejected a second conservative challenge to the healthcare law, he did so in a lawyerly dissection of its text. Conservatives said the law limited government premium subsidies to low- and middle-income policy holders who signed up on online exchanges “established by the state.” But Roberts and the court’s liberals concluded that Congress authorized the federal government to function in places of states that did not create their own online exchange, allowing insurance subsidies to continue for millions of Americans. For many conservatives, it was the last straw, unleashing the current round of criticism.

While his votes in favor of the healthcare law soured conservatives, they have not won over most liberals. They say Roberts and the conservative bloc have tilted the political playing field in favor of Republicans and against Democrats by giving money a much greater role in campaigns, and by undercutting voting rights for minorities and the poor.

“Roberts is likely to go down in history as an assertive chief justice who reshaped the election process. His court has voted to strike down nearly every campaign finance law to come before it,” said UCLA law professor Adam Winkler.

He is not the first Republican appointee to be denounced. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, like Kennedy and Souter, refused in 1992 to overturn the right to abortion set earlier in the Roe vs. Wade ruling. All three were slammed by Scalia and branded as turncoats by conservative activists.

Afterward, they were not as reliably conservative. O’Connor and Kennedy, both Reagan appointees, forged a moderate-conservative course. By the mid-1990s, Souter, an appointee of President George H.W. Bush, voted mostly with the court’s liberal bloc.

It’s unclear whether the criticism will affect Roberts. No one expects he will move decidedly to the left, but he has been increasingly unwilling to go as far as Scalia, Thomas and Alito would prefer.

One thing is certain: having just turned 60 this year, Roberts is far from finished.

ALSO:

House Speaker John Boehner to step down next month

Pope Francis, at U.N., warns of ‘boundless thirst for power’

Hillary Clinton’s big donors in California have found all sorts of reasons to be nervous

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.