A lonely veteran opened the doors to this American Legion post in order to save it

Reporting from Portland, Ore. — On a chilly Saturday afternoon in December, Sean Davis was tending bar at the American Legion in northeast Portland. Before him a dozen twentysomething musicians and visual artists were plotting an artistic response to Donald Trump’s election.

“If Hillary Clinton was president, they’d all be asleep right now,” joked the 43-year-old Davis.

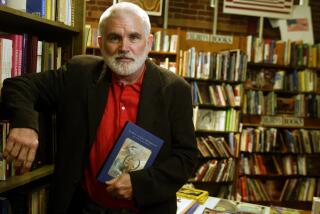

Bearded and burly, Davis was the only military veteran in the room, which wasn’t unusual at Post 134. The post commander, he is leading an experiment of sorts.

He believes that if the American Legion, a 97-year-old organization that helps veterans obtain government benefits and offers social support to them and their families, is going to survive a rapid decline in the veteran population, it must become more inclusive and open its doors to entire communities, not just veterans.

Post 134 looks a lot like left-wing Portland. It is strikingly young and feisty and plays host to indie-rock shows, sexual assault survivor groups, Sunday morning children’s bands, literary events, a food pantry, annual missionary trips to Haiti and trivia nights catering to gays, lesbians and transgender people.

“As far as I know, we’re the very first post to ever sign someone who was born a woman into the Sons of the American Legion, and someone who was born a man into the [Women’s] Auxiliary,” says Davis, a writing instructor at two local community colleges who fights wildfires during the summer.

With fewer than 1% of Americans serving in the recent wars, the gap between the military and the rest of society has never been greater. Davis wants to help bridge it, which in his view requires upending some traditions at the American Legion.

Leo Brill, one of the musicians who had come to join the anti-Trump effort, said the Legion had become an important part of the neighborhood.

“This is kind of a space that has the same values that we do, which is using art to make a difference in the community,” said the 24-year-old, who performs in a punk band called Mouthbreather.

This last week, amid an extreme cold spell, Davis turned the post into a 24-hour warming shelter. Two dozen homeless people — veterans and nonveterans alike — slept there Sunday night on donated cots.

Davis said the post could anchor the transformation of the entire neighborhood into “Haight-Ashbury here in Portland.”

Born to a teen mother who never finished high school, Davis grew up poor in rural Oregon.

Deciding the military offered him a way out, he enlisted in the Army in 1993. The day after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, two years after Davis had left the military to study art, he reenlisted in the National Guard.

He was on patrol in Iraq in 2004 when an improvised explosive device went off. He was left with several broken bones and a brain injury that affects his breathing. The blast earned him a Purple Heart and ended his military career.

He moved back to Oregon and took a job as a waiter while he tried to figure out what to do next.

“I went from conducting high-end missions to taking people’s orders for shrimp,” he recalled. “Those were the worst times of my life. I was pretty suicidal. I thought everyone had forgotten about me, that nobody was invested in the war.”

Using his rehab allowance, Davis graduated from college and went on to earn a master’s degree in writing.

In 2009, he decided to check out Post 134, housed in a gray quonset hut on Alberta Street that was built in the early 1950s by a mother who lost her son in World War II.

It fit the stereotype of a smoky lounge filled with white-whiskered vets. Davis was immediately put off by what he perceived as a rude bartender and an “exclusive, cliquish” atmosphere.

“Even as a Purple Heart combat veteran, I just felt like I didn’t belong there,” he recalled. “They just used it as a place to drink cheap alcohol.”

But in June 2014, around the anniversary of his getting injured, Davis was feeling alone. “I wanted to be around people who would understand,” he said.

So he returned to the post and asked how he could get involved. To his surprise, the old men said they hadn’t seen their commander in months and asked if he wanted the job.

Without really thinking about it, he said yes.

Davis proceeded to invite veterans he’d served with in Iraq to his post and soon installed a leadership slate that would support his rabble-rousing agenda.

His latest plan is to scrap the Legion’s groups for relatives — the Sons of the American Legion and the Women’s Auxiliary. Instead, he said, relatives, regardless of gender, will simply be known as “allies.”

“There was no negativity in their hearts when they set it up that way, but I have people coming into my post who say, ‘I don’t want to join something called a ladies’ auxiliary,’ ” he said.

The American Legion, which had 3.3 million members nationally at its height in 1947, still has 14,000 active posts and 2 million members nationwide. But only about 30,000 are veterans under the age of 40.

The Department of Veterans Affairs projects that over the next 25 years, the veteran population will fall from 21 million to 15 million and continue to decline. The drop-off presents a major challenge for the Legion, which has long relied on membership dues to keep its posts operating and to pay for its programs.

State and national officials have been pushing Davis to increase membership at the post. He said he had doubled membership to 350 veterans, though some are in arrears on their $40 annual dues, but he resents that focus.

“The older generation of American Legionnaires care more about membership than helping their communities,” he said.

Jim Willis, a 73-year-old Vietnam veteran and the Oregon state commander, said he appreciated much of what Davis was doing, but felt that membership was just as important. “That’s how you’re able to fund your programs,” he said.

As for the plan to eliminate gender groups for relatives and to call them allies instead, Willis said Davis should respect tradition. “I don’t care, necessarily, what he calls them within his post, but to change it from the current sons and the auxiliary, that’s just not something I can support,” he said.

Davis said bar revenue covered all the needs of Post 134. On any given day, it’s hopping, often with more nonveterans than veterans. The day after the anti-Trump artists met, for instance, a group of families from a local elementary school shared a breakfast buffet and swigged Pabst while a children’s band rocked onstage.

The post still holds veteran-only events, such as meetings in which those with combat experience come to discuss traumatic memories. But Davis said he believed that some of the greatest benefits to veterans would come from mixing with people who never served.

For all his willingness to challenge the American Legion orthodoxy, Davis said he also appreciated its stature.

“I know so many veterans starting nonprofits to do something, and I’m like, ‘Why reinvent the wheel?’” he said. “… Hey, I’m with the American Legion. I have instant credibility.”

Being the post commander has also raised Davis’ stature. This year he ran for mayor in a campaign managed by the post bartender and finished fifth among 15 candidates. He insisted he had no plans to run again.

He recently dabbled with running for Oregon commander of the American Legion but changed his mind, saying he’s happy running Post 134.

“I want to make positive change however possible,” he said.

Seely is a special correspondent.

ALSO

Meryl Streep ‘overrated’? Donald Trump fires the latest salvo in the culture wars

Supreme Court weighs the right to a refund for people who paid fines before they were freed

Is this the year the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge will be targeted for oil drilling?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.