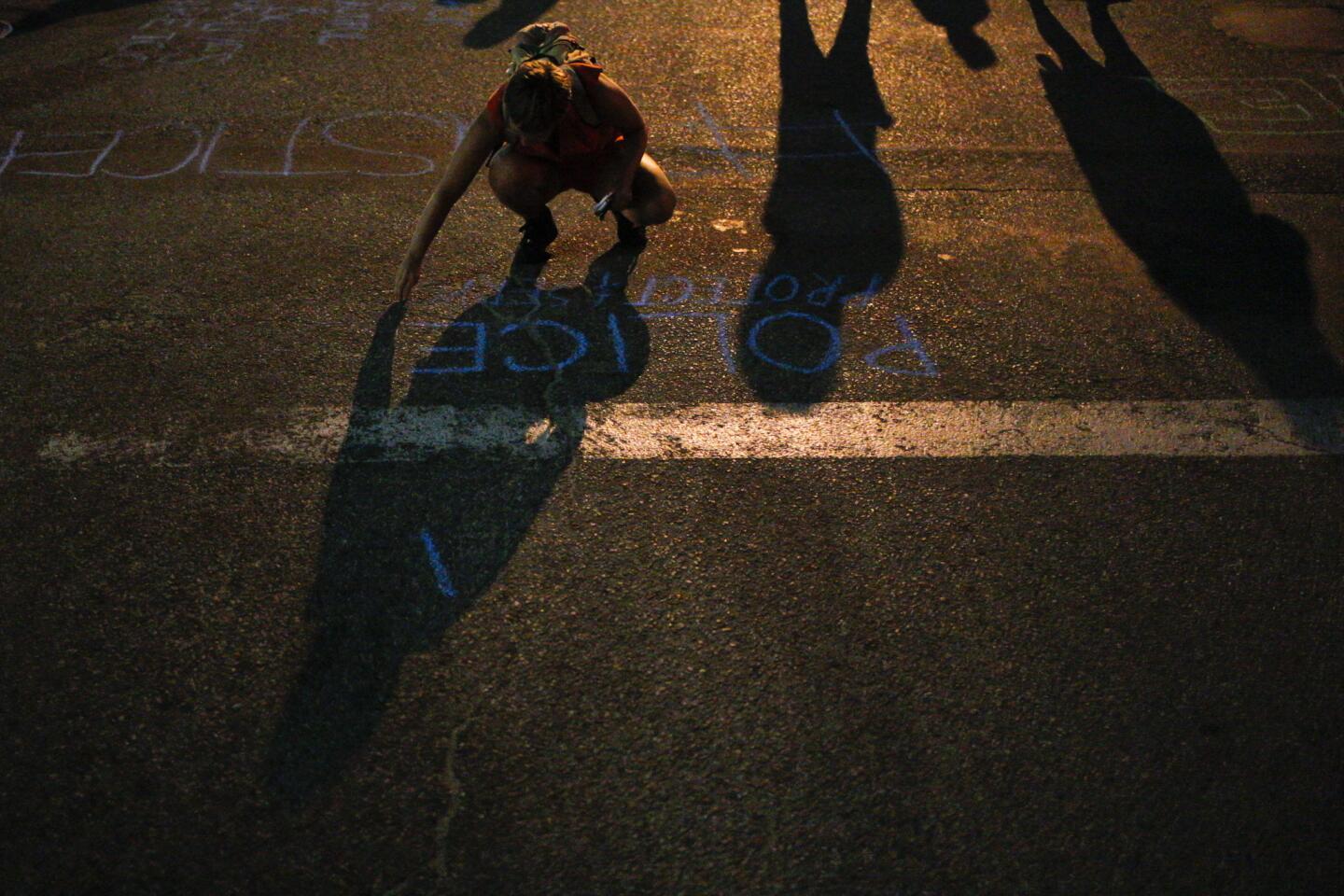

An uneasy standoff between police and protesters as Black Lives Matter returns to the streets

Reporting from Atlanta — When Atlanta Police Chief George Turner heard that five police officers had been fatally shot at a protest rally in Dallas, his heart dropped. He knew the police chief there, and felt for him. He also instantly realized that his own officer would now be on edge.

“People were upset,” he said Saturday. “They were feeling as if they were a target for issues they were not responsible for.”

As thousands gathered in protest this weekend over the recent fatal shootings of black men in Minnesota and Louisiana, the tension was tangible and the mood uneasy as a familiar ritual – protesters on the march and police standing by – returned to the streets of America.

In Rochester, N.Y., there were scuffles Friday night as officers attempted to push back the crowd, ending in the arrest of dozens of protesters. In Phoenix, confrontations broke out as police tried to prevent demonstrators from blocking ramps to a local interstate. Police in riot gear used pepper spray and fired bean bags, prompting some protesters to retaliate by hurling rocks, according to the Arizona Republic. And in Baton Rouge, La., protesters threw plastic bottles of water and cups of ice at officers in riot gear.

In California, the largest of several demonstrations was in downtown San Francisco, where an estimated 1,000 gathered. A smaller demonstration was held at the Huntington Beach Pier, and in Sacramento hundreds showed up holding signs outside the state Capitol and shouting a familiar call: “Hands up. Don’t Shoot.” At least two hecklers shouted at the demonstrators, but were quickly quieted by the crowd.

And in Baton Rouge, La., state troopers and members of the New Black Panther Party faced off on a highway on the outskirts of town – the troopers in riot gear, the protesters with their clenched fists raised.

Many police departments and protesters have adapted since the violent clashes in Ferguson, Mo., where there was widespread unrest in 2014 after a grand jury declined to indict Darren Wilson, the former police officer who shot and killed Michael Brown, an 18-year-old African American man. Ferguson police were criticized broadly for escalating confrontations, bringing in tear gas and military-grade riot gear and chasing protesters, resulting in a long week of gunfire, fires and looting.

A year and a half later, many police departments across the country are operating more gingerly, as they interact with Black Lives Matter campaigns.

As protesters swung into action in Atlanta late Friday, the city’s Police Department worked to develop a less antagonizing presence — policing remotely, via CCTV cameras and a helicopter, as well as asking officers to wear regular beat uniforms, rather than militaristic garb. Before protesters took to the streets, Chief Turner, an African American and 35-year veteran of the city police force, called Dallas’ police chief to discuss how to best shift police tactics to avoid confrontations.

“We were able to tweak the way we deploy resources,” he said, noting that more Atlanta officers worked undercover Friday night. “As opposed to being very overt, we have more police that are covert … It’s all part of the strategy we have to avoid intimidating the crowd.”

Protest organizers, in turn, also worked to de-escalate conflict. Atlanta’s demonstration, organized by the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People, the nation’s oldest grass-roots civil rights organization, worked with law enforcement to secure permits and plan the demonstration route. It also trained people to peacefully lead and disband the protest.

“I think everyone is upset, but this is not us versus law enforcement,” said Gerald Griggs, an attorney and vice president of the Atlanta NAACP. “We love our law enforcement officers, but we also want the citizens to return home safely and not be gunned down after a traffic stop.”

In New York City, the Rev. Al Sharpton told a gathering Saturday at his Harlem headquarters that the killings of the Dallas police officers were “wrong and reprehensible.”

“We are not anti-police,” he said, as he appeared with Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, who died in police custody two years ago in a case that helped inspire the Black Lives Matter movement. “We are not trying to kill police. We are trying to stop the killing of us.”

As 500 people gathered Saturday evening in a plaza in lower Manhattan at the base of the Brooklyn Bridge, several dozen police officers stood along the periphery of the crowd. There was little interaction between them and the protesters. As the crowd grew, additional officers arrived on the bridge and nearby streets, but seemed to keep their distance from the protesters.

Sabrina Johnson, 19, who was visiting from Virginia Beach, Va., said she had been very upset by the events of the week, and joined the protest for that reason.

“When I see these shootings happen, I see my little brother, my cousin or father in that position,” she said. “I don’t want to see their names become hashtags.”

In many parts of the country, the protests were small and peaceful.

In South Los Angeles, Jelecia Smith, 23, joined a small group of people standing on the corner of Florence and Normandie avenues, holding photos of people shot by police. Smith, who was born the year the officers who beat Rodney King were acquitted, and Florence and Normandie became the flashpoint in the riots that ravaged her neighborhood, said the shootings in Louisiana and Minnesota were “the last damn straw.”

“They’ve killed too many people who look like my brother.”

In Tampa, Fla., three dozen protesters stood Saturday in the Centro Ybor neighborhood, waving signs and chanting, “What do we want? -- Peace. When do we want it? -- now.”

Rappers the Game and Snoop Dogg lead a march Friday morning to the Los Angeles Police Department’s headquarters in downtown L.A.

In other cities, there were strained moments. Four Texas organizers of the Black Lives Matter protest that culminated in the shooting of the Dallas police officers were confronted Saturday morning when they attended a memorial in front of police headquarters. They said they were there out of respect.

As the Black Lives Matter activists surveyed piles of homemade sympathy cards, flowers and other tributes, a white man shouted, cursed and condemned them for “smiling and taking pictures in front of this.”

The activists backed away a bit as the crowd of several dozen people on the bustling street corner looked on, seemingly stunned. Before long, the man left.

“There was nothing for us to say to him,” said a member of the group, Dominique Torres, an attorney for the Dallas-based non-profit group Next Generation Action Network, which organized Thursday’s protest.

In Atlanta, a crowd of about 2,000 people — including Mayor Kasim Reed — attended a march organized by the NAACP. At one point, Sir Maejor, 28, who is president of the Greater Atlanta Black Lives Matter, said SWAT teams began to advance when protesters shut down Peachtree Street, causing activists to worry they might use tear gas or fire rubber bullets.

“We all had our hands up and shouted, ‘Hands Up. Don’t shoot,’” Maejor said, noting that seemed to calm the situation. “How can you shoot people with their hands up?”

Later, a group of protesters engaged in an hours-long standoff on the ramp of a downtown highway with state troopers, who formed a line to block demonstrators from marching onto the highway.

“We’re respecting their 1st Amendment rights,” Reed told reporters at the scene. “We’re the home of Dr. Martin Luther King. The only thing I ask is that they not take the freeways. Dr. King would never take a freeway.”

By the end of the night, three Atlanta protesters had been arrested by troopers — one for entering an interstate ramp, two for refusing to leave an exit ramp.

At about 3:30 a.m., the mayor managed to persuade a final knot of protesters to calls it quits and leave the highway ramp. Standing back, state troopers gave him the thumbs up and saluted him.

“I bent down, as if taking a bow to let them know: Thank you.”

Jarvie is a special correspondent who reported from Atlanta.

Staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske reported from Dallas, and Kate Mather reported from Los Angeles. Special correspondents Vera Haller and Les Neuhaus contributed to this report. Haller reported from New York and Les Neuhaus from Tampa Bay.

UPDATES:

6:58 p.m.: This story was updated with of the South Los Angeles gathering.

3:15 p.m.: This story was updated with details of New York City gathering.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.