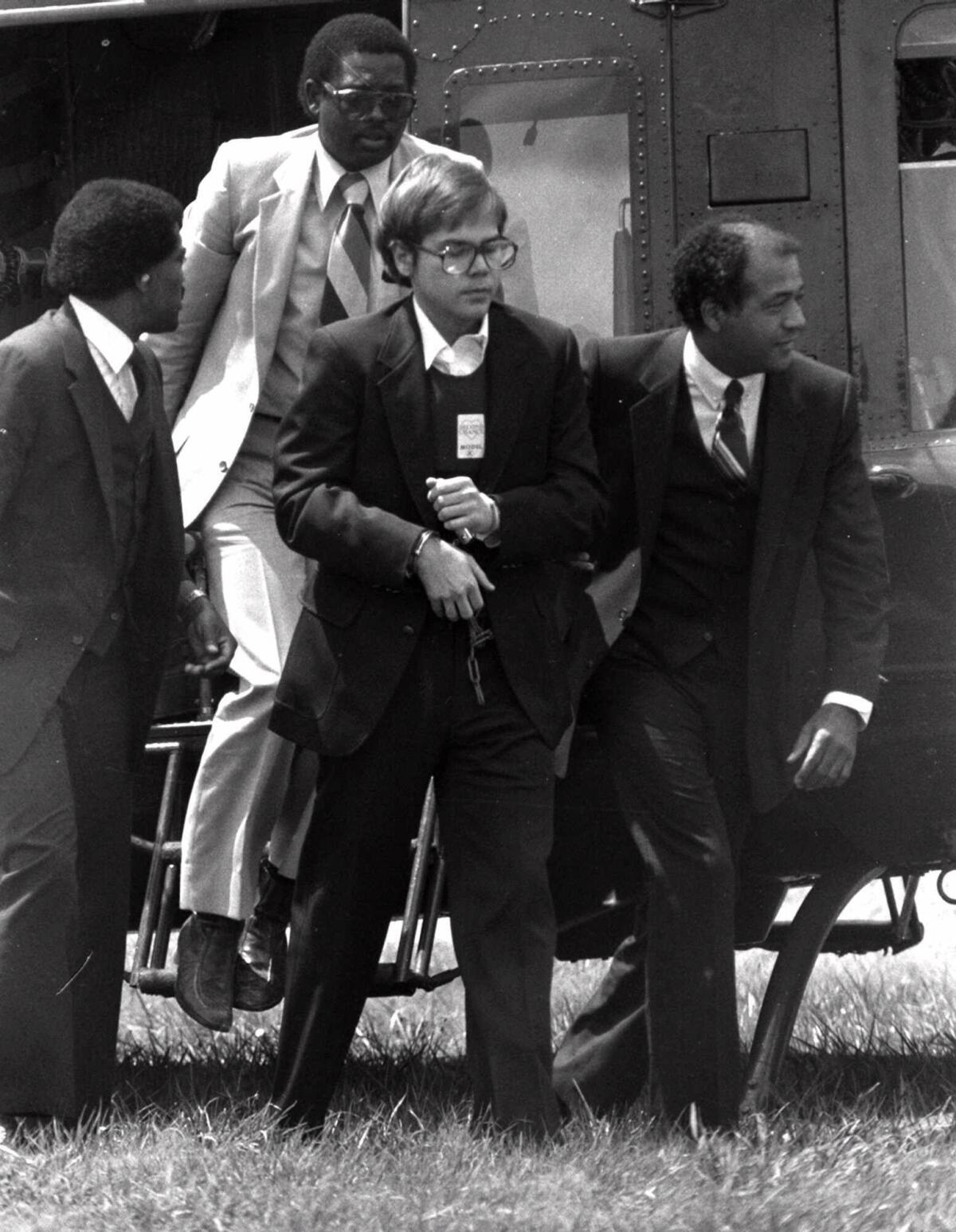

He once tried to kill President Reagan. Now John Hinckley says he’s ‘happy as a clam’

Reporting from Williamsburg, Va. — Two years after he was discharged from a mental hospital, John W. Hinckley Jr. lives in a modest house on a golf course, runs a small antiques business, adopted a cat named Theo, and drives for his mother and older brother.

“This is the best I’ve ever felt in my life,” he told a psychiatrist about his life in the historic colonial-era town of Williamsburg in coastal Virginia, according to court records. “I’m happy as a clam, to be honest.”

But at 63, Hinckley continues to face challenges, some universal and some unique to the man who shot and nearly killed President Reagan outside a Washington hotel on March 30, 1981.

He doesn’t like to exercise and in recent years has gained as much as 40 pounds. He walks with a limp and suffers from arthritis and hypertension.

He doesn’t have any close friends and has struggled with dating. Last year, the presidential assailant so badly freaked out a potential romantic interest that she called the police.

The insights into Hinckley’s first two years of freedom were revealed in psychological reports recently released by the federal judge overseeing his case.

The judge in November relied on the assessments to grant Hinckley more privileges from court-ordered oversight. Under U.S. District Judge Paul L. Friedman’s ruling, Hinckley is permitted to drive unaccompanied greater distances from Williamsburg.

And with the approval and oversight of his therapists, he can move out of his mother’s house and anonymously use the internet to sell antiques and books, and to display his artwork and music.

Hinckley has been under the supervision of mental health professionals since he was found not guilty by reason of insanity a year after he shot Reagan; the president’s press secretary, Jim Brady; a Secret Service agent, Tim McCarthy; and District of Columbia Police Officer Thomas Delahanty outside the Washington Hilton Hotel.

Hinckley shot the men to impress the movie star Jodie Foster; Reagan and Brady nearly died. Brady’s eventual death, nearly three decades later, was ruled a homicide because it stemmed from the 1981 shooting that left him partially paralyzed.

After years of gradually expanding Hinckley’s freedom from St. Elizabeths Hospital, a psychiatric facility, Friedman in July 2016 ordered him released to live with his mother in Williamsburg. He had been allowed to visit her for lengthy stretches before his release.

Doctors believe Hinckley’s major depression and underlying psychotic disorder have been in full remission for three decades, court records show.

Over the last two years, he has regularly attended individual and group therapy sessions, the records show. He works with a music therapist, and met monthly with a psychiatrist.

He has made the 150-mile trek monthly to Washington for an appointment with the psychiatrist overseeing St. Elizabeths and the city’s Department of Behavioral Health.

According to the reports, Hinckley’s therapists agreed that his transition from St. Elizabeths to Williamsburg had been smooth and that he had matured and grown increasingly independent.

Hinckley’s attorney, Barry Wm. Levine, agreed. “He is doing beautifully, perfectly. He is compliant with every requirement of the court and he is happy.”

Hinckley lives with his mother, Jo Ann, and his older brother, Scott, in the gated community of Kingsmill, near the scenic James River. He has a bedroom with a king-sized bed and his own paintings on the walls.

Hinckley does most of the driving for the family, shuttling his brother and mother to appointments and meetings. He also shops for groceries and handles some cooking.

He took on added responsibilities in August 2017 when his mother fell and broke her hip, becoming her primary caregiver. She is doing better, but her mortality is on her son’s mind.

“He described ‘working hard’ to take care of his mother in order ‘to give her good things in her final — I don’t want to say days, but time,’ ” the records recall Hinckley telling a psychologist.

Jo Ann Hinckley spoke highly of her son, telling a psychologist that “John just does everything he needs to do here for me. It’s like having a maid in the house.”

A month after his mother’s hip injury, Hinckley opened a small business selling antiques and books anonymously in an antiques mall. It has been a profitable venture, earning several hundred dollars a month. He is seeking to expand the operation to allow him to sell his books anonymously on the internet.

Shoppers, sellers and employees at the mall said Hinckley had kept a low profile, and therapists agreed that Hinckley had done a good job avoiding the limelight. Interviews with dozens of local residents revealed that few even knew he lived in town.

Tom Dorman, a local resident, has spotted him several times at a mall, but he said Hinckley did not call attention to himself. Once, he opened a door for Dorman at a local grill.

“He’s a nice, quiet guy,” Dorman said. “He acts like everyone else.”

Hinckley told his therapists that it had been relatively easy to avoid being recognized, noting that although his name is well-known, his appearance is not decades after his face was on every front page.

“No one ever gives me a second look,” he said.

Hinckley has long struggled in relationships with women and dating, and that remains the case.

Most of his relationships were with women suffering from mental illness whom he met at St. Elizabeths or in other treatment settings. It has been difficult for him to establish connections once women learn about his past.

The reports show he was reprimanded for approaching a woman after a group therapy session in Williamsburg, which is against the rules. He said he was just trying to be friendly.

When he came across a young woman on a walk, his therapists urged him to send a letter asking her to coffee.

But the note backfired when she saw the signature, “John Hinckley.”

“She was not aware of Mr. Hinckley’s identity during their conversation,” one of the reports concluded, “and became uncomfortable once she learned his last name from the letter.”

The unidentified woman called police, who alerted the U.S. Secret Service.

Hinckley and his therapy team agreed it would be a good idea to let women know his full name before asking one on a date. They discussed and rejected the idea of permitting him to participate in online dating, the reports show.

Outside of romance, Hinckley has struggled to maintain close friendships. One buddy got married and moved away. Another died. He lost the support of a photographer and mentor who became ill.

He remained friends with a woman who had been a fellow patient at St. Elizabeths, making it clear he was not interested in romance. Therapists were impressed by Hinckley’s decision to limit the relationship to a “supportive friendship.”

He became friends with another woman, a former participant in his group sessions. They mostly watched TV and movies and went for walks, though he was concerned she abused unspecified substances. He knew any relationship would not have long-term potential.

When the woman killed herself in August 2017, Hinckley hadn’t seen it coming. “It rocked his world,” his case manager reported.

Psychologists have encouraged Hinckley over the years to paint, take photographs, write songs and play music, believing such avocations were therapeutic.

In 2018, his interest in art waned because he was not permitted to play music or display his paintings or photography in public, even anonymously on the internet.

Hinckley eventually dropped all three hobbies because, as he reported, “no one is going to appreciate it other than my closet.”

Under the judge’s latest ruling, that will change. Working with his therapists, Hinckley will be permitted to post his music and artwork anonymously on the internet.

But such forays will likely remain as low-key as his other pursuits. The judge ruled he cannot profit from his work, nor can he even communicate with his patrons.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.