In the ‘land of the free,’ are you free to sit out the national anthem?

When San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick remained seated while teammates stood with hands over hearts for “The Star-Spangled Banner,” he set the national debate about race on a collision course with three pillars of American patriotism: football, the military and police.

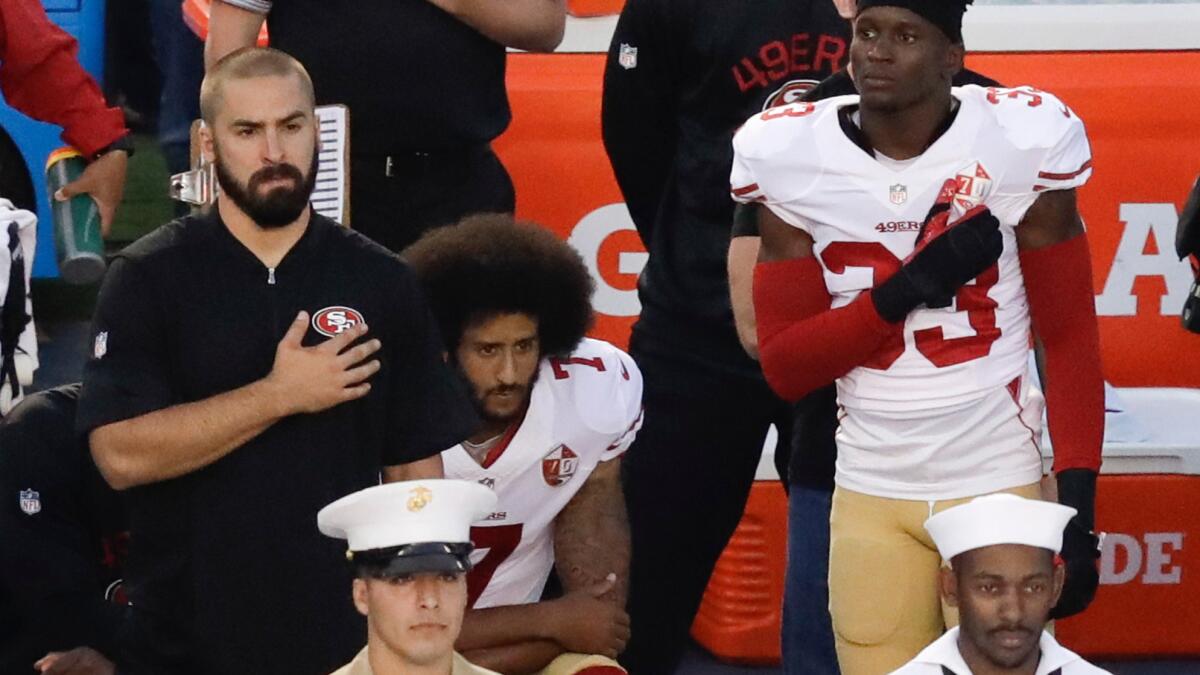

And it will only continue: On Thursday, Kaepernick took part in a final preseason game against the Chargers in San Diego — billed as the annual Salute to the Military night. Kaepernick kneeled when the patriotic music started. He was joined by fellow 49ers player Eric Reid.

The night included a marine band; a parachute team with retired Navy SEALs leaping into the stadium; and 240 sailors, Marines and soldiers presenting a large American flag while a Navy officer sang the national anthem. On Thursday night, Seattle Seahawks cornerback Jeremy Lane also sat on the bench during the anthem ahead of a game against the Oakland Raiders.

African American athletes have long grappled with complicated feelings about patriotism as they represent a country that many say hasn’t always fully embraced them. And though challenging patriotism has always been controversial, Kaepernick’s protest comes at a time when views on policing and race have, in many circles, become barometers of one’s commitment to the nation.

The country is divided between Black Lives Matter — a movement whose activism over police shootings of black men Kaepernick tweets about to his 900,000 followers — and Blue Lives Matter. Gold Star moms and Green Berets have taken sides, saying the 28-year-old has either disgraced veterans or honored them. Thousands of men and women have tweeted photos of themselves with the hashtag #VeteransForKaepernick.

Politicians have entered the fray: Donald Trump has suggested Kaepernick find another nation to call home; the White House defended the quarterback’s right to protest what he says is a flag “for a country that oppresses black people and people of color.”

Sports figures have also weighed in: New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees accused Kaepernick of insulting a flag that is “sacred,” and which has given him the “freedom to speak out,” while NBA legend Kareem Abdul Jabbar hailed him, saying his stance is “truly patriotic.”

Kaepernick’s own birth mother — she is white; he is a biracial, adopted black man — tweeted that he was “bringing shame.” The furor over his actions has continued for days.

Kaepernick has said that he himself has personally experienced racism by police. That includes being pulled over while driving and, while studying at the University of Nevada, having officers come into his house with “guns drawn on us” because, he says, a roommate was moving out and “we were the only black people in that neighborhood.” He says he wants to use his position to help those who “don’t have a voice.” That includes more activism that is “in the works.”

The quarterback, who spoke on the phone with at least one leader of the Black Lives Matter movement this week, said he’s not against the military service members who “fight for liberty and justice for everyone.”

“I am going to continue to stand with the people who are being oppressed,” Kaepernick said in a locker room interview on Sunday, three days after controversy broke out over the anthem protest, which he said was in part a statement against shootings of black men and police “getting paid leave for killing people.”

“To me, this is something that has to change and when there is significant change and I feel like that flag represents what it is supposed to represent and this country is representing people the way it’s supposed to, then I’ll stand,” he said.

Peter Dreier, an Occidental College professor who frequently writes about the politics of sports, suggested Kaepernick had seized a unique moment in American history.

“We’re in the middle of an election campaign that adds to the tension. The Black Lives Matter [movement] has become a part of our political discourse that nobody can avoid addressing. The police shootings and mass killings have raised an awareness of guns. And more and more athletes are educated,” said Dreier, author of “The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame.”

“All these things are in the mix that make it a ripe time for controversy over racism,” he said.

Aside from schools, it’s been sporting events where patriotism has long shined. “The Star-Spangled Banner” has been part of the pregame ritual for baseball since 1942 and sung ahead of NBA games since the league’s creation in 1946. The NHL started playing the anthem in 1946 and has since the 1970s let teams substitute it with “God Bless America.” Since its formation in 1996, Major League Soccer has adhered to the anthem tradition.

Dick Flacks, a retired sociology professor at UC Santa Barbara, notes that those earlier anthem trends had something in common: They kicked off during or just after World War II as a way to boost American patriotism.

From then on, the connections between sport, the military and patriotism grew. Two days after President Kennedy was assassinated, NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle added moments of silence and flag ceremonies to Sunday games played across the country. During the first Gulf War, flag decals began to appear on players’ uniforms. Since Sept. 11, 2001, many baseball stadiums have replaced the traditional seventh-inning stretch “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” with “God Bless America.”

The Defense Department has also gotten involved. Last year, a Senate report said it had doled out at least $8.8 million in a now-discontinued “paid patriotism” program in which it gave money to major sports teams to let servicemen and -women sing the anthem and unfurl flags on game fields.

Over the years, protests like Kaepernick’s have also become common. One of the most controversial was in 1968, when Olympic runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in black power salutes while the national anthem played during a medal ceremony in Mexico City. (“I support him because he’s bringing the truth out – regardless of how done,” Smith recently said of Kaepernick.) A year earlier, Muhammad Ali was fined and banned from boxing for three years after refusing to be inducted into the Army, citing his Islamic faith as well as racism against black Americans.

In 1972, Jackie Robinson made his own views known in an autobiography. “I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag. I know that I am a black man in a white world,” he wrote in “I Never Had It Made.”

In Southern California, Los Angeles High’s black football coach Hardy Williams made waves in 1985 when he turned his back when the anthem was played before games. (This week, he said he’d decided Kaepernick was “immediately my favorite player.”)

But there is also an intense scrutiny on athletes that can make them the target of the American public’s ire even if they are not trying to protest. Last month, black Olympic gymnast Gabby Douglas issued an apology of sorts after she was fiercely criticized for not holding her hand over her heart during the national anthem at the Summer Games.

Kaepernick himself has indicated he didn’t intend to cause a stir by sitting during the song, which he had done previously in the preseason without getting noticed. Also unnoticed until this week: photos that show Kaepernick during practice last month wearing socks that depict police as pigs. On Thursday, Kaepernick said in a message posted to Instagram that he wore the socks as a statement against “rogue cops” that “put the community in danger.”

It’s unclear how Kaepernick’s protest will play out as the regular season kicks off, how long it will go on, or even how long he will stay with the team. Speaking to a gaggle of media in the 49ers locker room on Sunday, the man once seen as one of the league’s most promising young players before being beset by injuries and losses said he has no regrets about now being one of its most divisive.

“I think there’s a lot of consequences that come along with this. There’s a lot of people that don’t want to have this conversation; they’re scared they might lose their job or they might not get the endorsements, they might not be treated the same way,” he said. “And those are things I’m prepared to handle and those are things that, you know, other people might not be ready for. It’s just a matter of where you’re at in your life, where your mind’s at.”

“At this point, I’ve been blessed to be able to get this far and have the privilege of being in the NFL and making the kind of money I make and enjoy luxuries like that. … But I can’t look in the mirror and see other people dying in the street that should have the same opportunities that I’ve had and say, you know what, I can live with myself. Because I can’t if I just watch.”

Jaweed Kaleem is The Times’ national race and justice correspondent. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

ALSO

Colin Kaepernick says the pigs on his socks were only meant to represent ‘rogue cops’

Opinion: Colin Kaepernick’s wealth and fame don’t protect him from police brutality. Here’s proof.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Colin Kaepernick’s protest is ‘highly patriotic’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.