Muslims have lived for more than 100 years in this Iowa city. Now they’re wondering how they’ll survive under Trump

Reporting from Cedar Rapids, Iowa — On a church-lined street in this eastern Iowa city, not far from the cornfields that define the region, Syrian, Indian and Somalian families trickled into a white building topped with a blue minaret. They were full of questions and praying for answers.

“This is a wake-up call,” Ramsey Ali, a 29-year-old graduate student, told the crowd of 50 gathered at the Islamic Center of Cedar Rapids. “We have to do something.”

These heartland Muslims, who belong to one of the oldest Muslim communities in the United States, had gathered in search of relief and unity.

Instead, they found themselves just as divided as the rest of the nation.

Since Donald Trump’s election, dozens of mosques have hosted emergency forums like the one held here Saturday, trying to calm congregations fearful and confused over their prospects under his presidency. Top imams have convened conference calls and strategized with civil rights groups over what many see as the inevitable assaults on their faith. Some Islamic groups have cautiously vowed to work with the new president, while others have called on him to repudiate his statements on Islam — a faith he just months ago said “hates” Americans.

In Cedar Rapids, the second-biggest city in Iowa, the debate over life under Trump has taken on extra meaning. Muslims, who number about 5,000 in Linn County, are a small minority in the region of 218,000 people yet deeply ingrained in its history.

The community dates to the early 1900s, when small groups of Muslims and Christians immigrated from what is now Lebanon. They worked in grocery stores and local industries and saved to build a two-story social club that opened in 1934 near downtown. The Muslims also used it as a mosque and in 1971 built a larger building, where the community met last week. The original mosque, called the Mother Mosque, is still used for special events and stands in a neighborhood just west of the Cedar River that last week was scattered with Trump-Pence posters. Around the mosque, signs proclaim it as a state landmark.

“We survived a world war, we survived the Iran hostage crisis, we survived 9/11,” said Hassan Igram, 61, whose grandfather helped found the mosque. “But this situation is a little different.”

Before Trump was elected, with the help of a victory in Iowa, he had at points vowed to ban Muslims from immigrating, said he was open to government spying on certain mosques and once said he would “absolutely” have a registry of all Muslims. Since his win, civil rights groups have raised alarms about a jump in attacks on Muslims and other minorities across the country by Americans emboldened by the new presidency. Some Trump supporters also have been hurt in scuffles.

At Cedar Rapids’ Islamic center, where about 150 people usually attend weekly Friday prayers, families streamed in on Saturday with their kids for an event titled “Raising a Family in the Times of Fear.” It was ostensibly a potluck dinner and slideshow presentation about how to talk to children about fears of Islam. It was led by Ali, a psychology doctoral student at the University of Iowa.

In actuality, it was group therapy for adults and high schoolers in shock over the election and wondering about their future.

As congregants sat at tables in front of a projector, eating rice pilaf and kebabs, Ali presented a series of data points and guides. They covered anti-Muslim violence, mental health among Muslims, and civil rights resources.

But mostly, he peppered them with questions about their state of mind. The group talked for hours as it gradually dwindled in size, interrupted only by the recorded sounds of the call to prayer over the mosque speakers.

Ali asked what the Muslims in the room needed to do after the election.

You know, everyone keeps saying his win is from racism from white people and people that hate Islam. Not everyone who supports him is a bigot.

— Mokhtar Sadok, a Tunisian American engineer in Cedar Rapids

“If we want to see a change of the attitude of the non-Muslims about the Muslims in Iowa, it will not happen with us staying in our homes, within our cubicles at work or within this masjid. The only way that it will work is if we go out. Allah has chosen for us to live within America for a purpose. Until we fulfill that, that stigma that Muslims are scary people will not go away,” said Hala Azmeh, a 47-year-old Syrian American schoolteacher who runs the mosque’s education committee.

Her 15-year-old daughter agreed but was less optimistic.

“We need to personally go up to people. I don’t know how to do it, honestly. I feel like we’ve tried several ways, but nothing is really happening,” said Noor Azmeh. She had joined a Muslim youth group this year to clean up a homeless shelter with an interfaith organization, one of several regular outreach activities the mosque runs.

Ali asked what led to Trump’s victory.

“You know, everyone keeps saying his win is from racism from white people and people that hate Islam. Not everyone who supports him is a bigot. My neighbor supported Trump. He had a sign in his yard,” said Mokhtar Sadok, a 51-year-old Tunisian American engineer. “He knows we’re Muslim. We’re friendly.”

“No, I think it’s definitely the white people. I work with them,” whispered an Indian American woman.

Ali asked whether Muslims should debate with Trump voters and people who disliked Islam. Fake news on Trump and Hillary Clinton, including false sources on Islam, had proliferated during the campaign, spreading on Facebook.

“When you put yourself into the situation where you debate Islam and another religion, it can do more harm than good. Do we really want to debate, or do we want to just say what Islam is and walk away?” said an African American woman. Earlier, she said she thought people had been trailing her car in recent weeks because they saw her hijab.

Ali asked whether uniting with other minorities was the key to a better public understanding of Islam under Trump.

“The best way to help ourselves is to help others,” said Brittanie Shah, a 31-year-old white convert to Islam who is a teacher in North Liberty, Iowa. “Part of me is like, ‘People should really rally behind us,’ but were we rallying around other minority groups before? I know some beliefs like LBGT rights are in conflict with our religion. But it seems disingenuous to ask for support until we support others.”

Her husband, Faraz Shah, suggested an easier way to make allies. “I’m from conservative southwestern Indiana. After 9/11, we began to do international food fairs to get people to meet Muslims. We could try that here,” he said.

Those gathered on Saturday wondered how much President Trump would be like candidate Trump when it comes to Muslims.

Trump has largely remained silent on Islam since his election and, in the last months of it, had began to soften some of his positions. His ban on Muslim immigration, announced last year, later morphed into an “extreme vetting” of would-be immigrants. After he said in March that Islam “hates” Americans, a spokeswoman said he meant to speak only about “radical Islam.” Although he has spoken since his election about Obamacare — which he now wants to keep parts of — and his plan to proceed with a promise to deport immigrants with criminal records, he’s been mum on mosque surveillance and Muslim registration.

Noor Azmeh, who wears a hijab, said she thought the group was too negative.

“I have the fear and anxiety of walking down the street,” she said. “But there are so many people are out there who are so nice to us. Me and my mom have been in the store and there are random people who just stare at us, and they’ll find a way to somehow just come to say hi to us. They’ll ask us how we are doing. It happens at Wal-Mart; it happens wherever you go.”

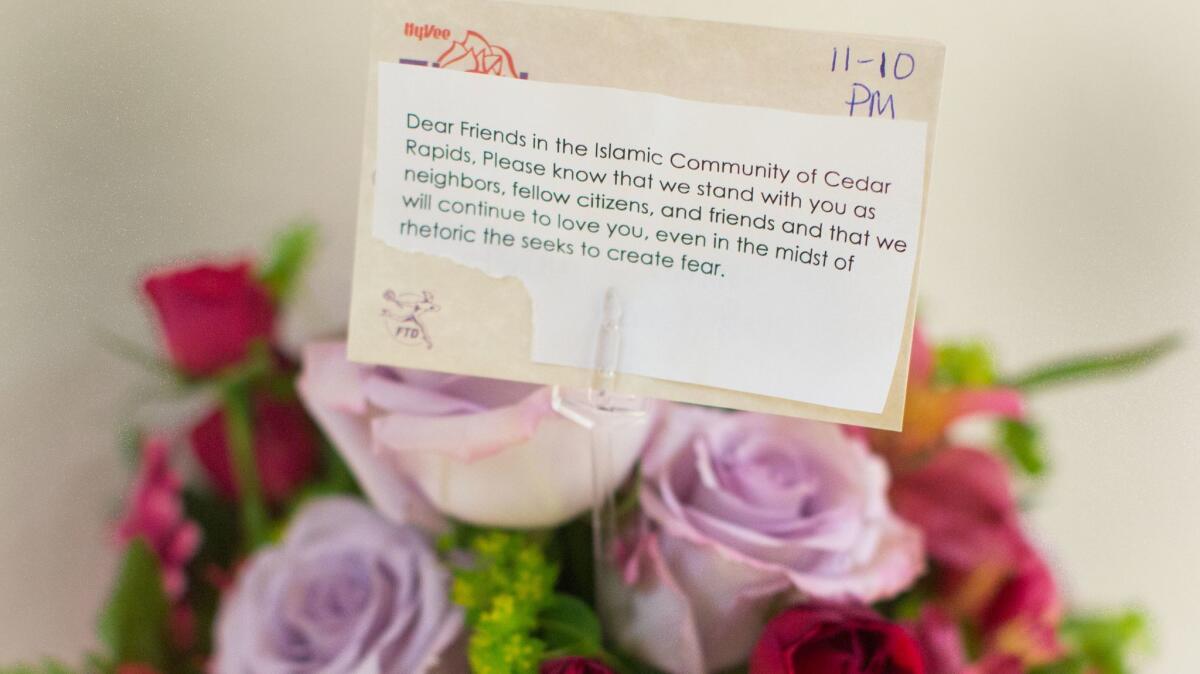

It’s happened in the days after the election, when three pots of flowers showed up at the mosque’s front door with messages of encouragement, and a civil rights attorney dropped by and left his business card. At the Mother Mosque, the historic building the community operates, someone had left a fruit basket with oranges, strawberries and chocolate bars after election night. Tucked into the stems of a bouquet of yellow carnations, a notecard had a message for the Muslims.

“You are loved. Our country is stronger & better with you in it,” it said. “Do not live in fear, there are loving people all around you!”

ALSO

When Trump says he wants to deport criminals, he means something starkly different than Obama

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.