Video captures Missouri protesters’ clash with media

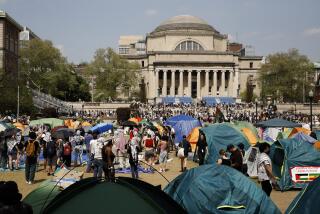

Reporting from Columbia, Mo. — The warning signs circle the protesters’ tent encampment like guard towers: No media allowed. The activists say the tent city is meant to be a safe space.

One problem: The tents are in the middle of a public, 1st Amendment-protected university quad.

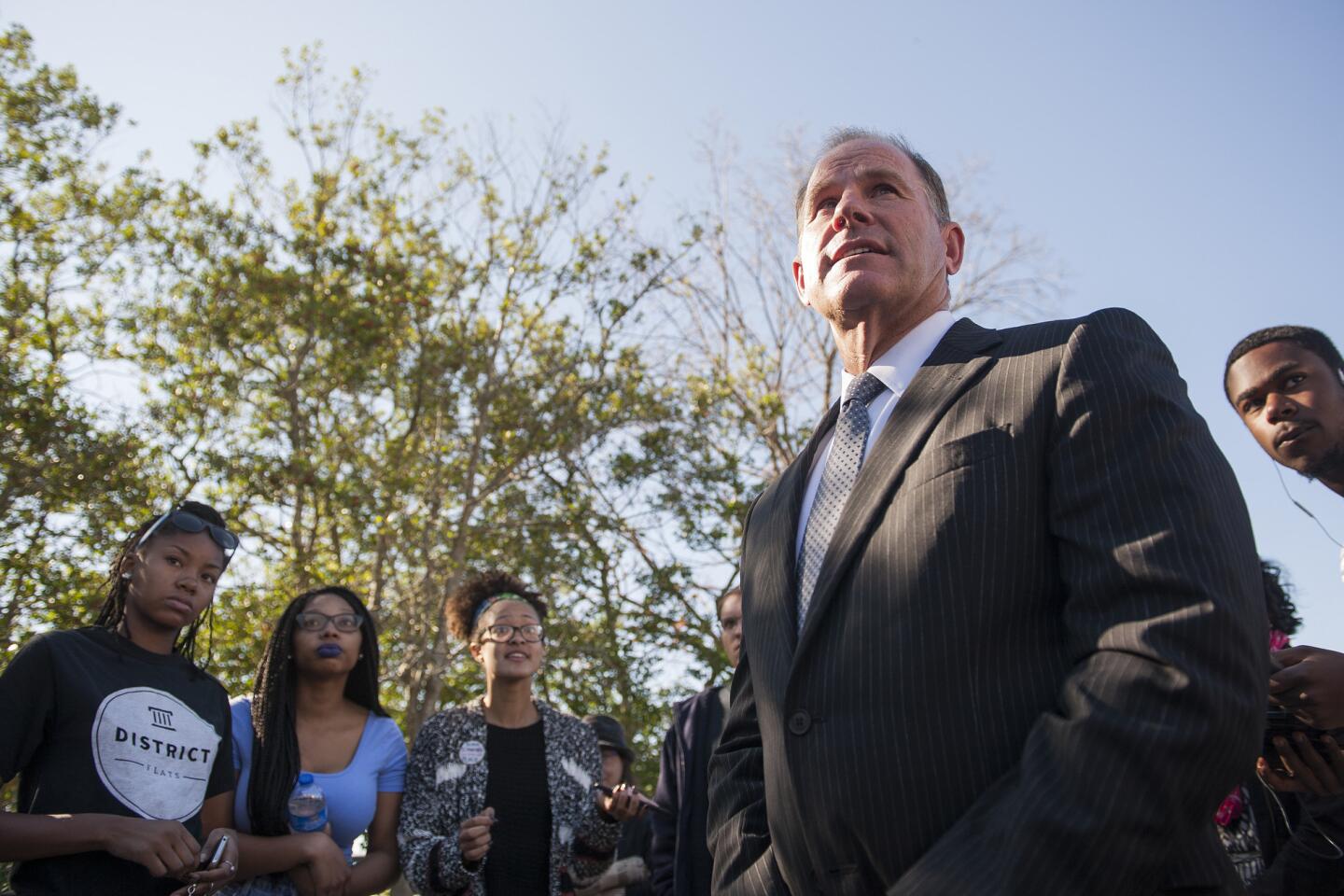

The story of a student uprising led by black activists at the University of Missouri took an unexpected turn Monday when protesters and student journalists got into a clash over access.

A video of protesters surrounding and shoving a student photographer out of the way has since prompted indignation from journalists who say activists have gone to such great lengths to protect their own privacy and space that they have infringed on the rights of others.

The University of Missouri has one of the nation’s largest and most prestigious journalism schools, and the story of the activists who forced the university system’s president and the university chancellor to announce their resignations Monday surely rates among the biggest stories in the university’s modern history.

Activists with Concerned Student 1950 — the main activist group involved with the recent protests — have strictly limited their contact with the media.

As Concerned Student 1950’s members filed off an amphitheater stage Monday afternoon — still calling for more change and more meetings with top university officials — other activists blocked journalists from asking questions.

“Why don’t you want to talk to the media?” one reporter asked.

“That’s their choice,” a man blocking reporters responded. “They don’t want to. They don’t have to justify that.”

Photojournalism student Tim Tai, 20, a senior from St. Louis, Mo., had taken an assignment with ESPN and hustled over to the tent encampment Monday after University of Missouri System President Tim Wolfe announced his resignation over complaints he had not done enough to address racism on the campus.

When Tai arrived, students were chanting, singing and celebrating. Wolfe’s resignation amounted to a major victory to them. Tai tried to capture the moment.

He told The Los Angeles Times that he was looking for pictures that “tell the story” and capture how the protests fit into other demonstrations by black activists around the nation. The glaring daylight wasn’t great, but he tried to get shots of the tents, which he said were evocative of similar protests in the university’s history.

But shortly after the celebration began, a ring of protesters assembled around the tent encampment and then marched outward to push away the media that had gathered at the scene.

In the video, taken by another journalist and uploaded to YouTube, Tai refuses to budge.

“You don’t have a right to take our photos,” a demonstrator told Tai, who responds that he has a 1st Amendment right to photograph on the quad.

“Shame! Shame!” the protesters chant at Tai. “Hey hey! Ho ho! Reporters have got to go!”

“I have a job to do!” Tai tells one demonstrator. “I’m documenting this for a national news organization. This is the 1st Amendment that protects your right to stand here and mine! ... The law protects both of us being here.”

Other demonstrators — including a middle-aged protester — got very close to Tai and pushed him backward away from the encampment.

One person in the video, University of Missouri professor Melissa Click, can be seen on the video grabbing a videographer’s camera and telling him, “You need to get out,” and then shouting to other protesters: “Who wants to help me get this reporter out of here? I need some muscle over here!”

The video drew a stern rebuke from the editor of the Columbia Missourian, a university newspaper staffed with professional editors and student reporters and photographers. Tai had been a photographer at the paper a year earlier.

“I’m pretty incensed about it,” executive editor Tom Warhover told The Times. “I find it ironic that particularly faculty members would resort to those kinds of things for no good reason. I understand students who are protesting and want privacy. But they are not allowed to push and assault our photographers -- our student photographers.”

“I got in a bit of a shouting match, and I regret that,” Tai said later, sitting inside an empty office at the Columbia Missourian, where he fielded media calls and looked at his social media accounts. A glance at his Facebook page showed that he had 34 new friend requests. A glance at his Twitter account revealed he had hundreds of new followers.

“I really hope I haven’t tweeted anything bad in the last year,” Tai murmured to himself.

Tai acknowledged that the demonstrators had a point, since he does recognize there are situations that are sensitive to photograph, but he said that he tries to figure out “how to cautiously or delicately approach these stories without overwhelming people.

“I don’t think everyone there is super anti-media, but I think there’s misunderstanding about what we do,” Tai said.

Tai told The Times that he recognized one of the people at the scene as one of his former professors.

Responding to criticism from journalists over the video, Concerned Student 1950 tweeted from its group account, “We truly appreciate having our story told, but this movement isn’t for you.”

Tai said he wasn’t scared by being surrounded and pushed, but he was frustrated.

He was in a similar situation when covering last year’s protests in Ferguson, Tai said — except “it was the police doing it then.”

MORE ON THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI

Missouri football players show the power of unity through boycott

Protesters celebrate after top University of Missouri leaders resign over racial turmoil

University of Missouri football team and coach join protest to oust university leader

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.