Why Michigan has been lurching from crisis to crisis

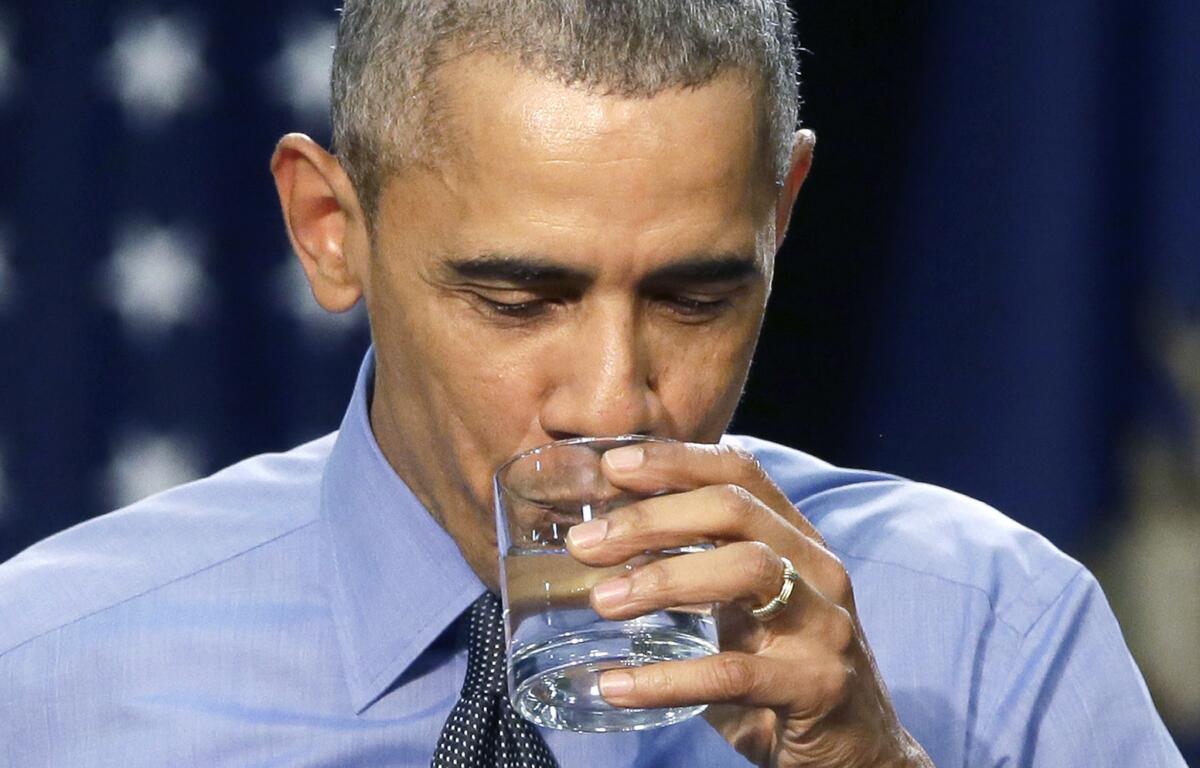

On Wednesday afternoon, President Obama put a glass of filtered Flint, Mich., drinking water to his lips and took a sip.

His message was clear. “I’ve got your back,” Obama told residents in a televised address, drawing cheers from the audience.

“I want all of you to know that I’m confident Flint will come back,” Obama said, jabbing the air with his finger as his voice rose. “I will not rest, and I’m going to make sure that the leaders at every level of government don’t rest, until every drop of water that flows to your homes is safe to drink, and safe to cook with, and safe to bathe in, because that’s part of the basic responsibilities of a government in the United States of America.”

Obama’s visit to Michigan this week was a gesture of support for Flint residents, after government regulators allowed the city’s drinking water to be poisoned with toxic lead after improper treatment.

But his arrival also underscored a painful truth: Michigan is still lurching from crisis to crisis years after the decline of manufacturing jobs in the state first began sending local governments into a tailspin.

This week, Detroit public schools shut down for two days, when teachers protesting a funding crisis that has left the state’s largest school district almost $500 million in debt took their sick days en masse. They were concerned the district might not have enough money to pay their salaries for the next two months.

“It’s astonishing that teachers and other school employees have been working diligently to educate our kids in under-resourced schools with deplorable conditions, yet they had to fight to get what they’re due,” Ivy Bailey, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said in a statement.

Michigan’s House of Representatives is considering a Republican-backed package that would send $500 million in state aid to the school district. But state Democrats are concerned the funding isn’t substantial enough, according to the Detroit News, and would impose too many restrictions on collective bargaining.

The school system’s funding crisis comes three years after the city of Detroit -- which operates separately from the school district -- filed for America’s largest-ever municipal bankruptcy. Once one of America’s mightiest cities, Detroit had accumulated $18 billion in debt.

“What happened in Detroit must never happen again,” Judge Steven Rhodes said when the city emerged from bankruptcy in 2014.

Though each crisis has been distinct in its particulars, there are recurring themes: fleeing residents and budget shortfalls following the decline of Michigan’s once-mighty manufacturing industry.

“The urban decay, the abandonment of Detroit and Flint is the common denominator,” said Eric Lupher, president of the Citizens Research Council of Michigan, a nonpartisan think tank.

Between the 2000 and 2010 censuses, Michigan was the only state to lose population. Detroit has fewer than half of the 1.8 million residents who lived there during its heyday. Flint had more than 200,000 residents in the 1960s; now it has fewer than 100,000.

The cities’ tax bases shrank as residents fled to the suburbs, leaving government officials holding the bag on retirement obligations and other pricey services, with fewer people to pay for them.

Republican Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder, a venture capitalist first elected in 2010, has called Michigan “the comeback state” in recent years, pointing to declines in unemployment, a return of some manufacturing jobs and a more stable state budget.

But the crisis in Flint in particular has threatened the final term of Snyder’s administration.

The water switch-over plan was approved by a state emergency manager appointed by Snyder to help stabilize the city’s precarious financial situation. The move was meant to save money and cut down on rate increases for Flint’s impoverished residents.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

An investigation led by Michigan Atty. Gen. Bill Schuette, a Republican, brought felony conspiracy charges against two state environmental employees accused of falsifying lead tests as Flint River water corroded old pipes and released toxins.

Investigators did not identify a motive for the alleged coverup. But a Flint city employee who was also charged, Michael Glasgow, said previously that they were under pressure from state officials to quickly complete the switch to Flint River water.

Glasgow pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor charge of neglect of duty Wednesday, as part of a plea agreement with the state attorney’s office in which he agreed to cooperate in the ongoing investigation that will probably focus on the state’s role.

In a state budget proposed in February, Snyder identified Flint and the Detroit school crisis as two of the biggest challenges facing the state.

Detroit’s public schools have been near bankruptcy after nearly half its students fled the district since 2002 -- either to follow their parents out of town, or to go to charter schools.

That posed a particularly painful budget problem for the district, since the state ties funding to student enrollment.

“It sounds good in theory,” Lupher of the model. But when the funding plan was implemented more than two decades ago, “I don’t think they had in mind the sort of economic decline that the state would go through the first decade of the century, and the effect of charter schools on the whole thing.”

ALSO

Michigan charges three officials with felonies in Flint water crisis

Op-Ed: Flint’s toxic water crisis was 50 years in the making

A ‘man-made disaster’ unfolded in Flint, within plain sight of water regulators

Follow @mattdpearce

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.