As historically black colleges struggle, Bennett College for women fights to stay afloat

GREENSBORO, N.C. — Pilar Hughes watched students crisscross the wide quad at the center of campus, remembering her first year at Bennett College.

The tiny classes. The soul food lunches served on Wednesdays. The sisterhood and the overwhelming sense of self-worth the all-women’s black college offered.

“There is so much love and community here,” the freshman said on a warm spring morning. “I’m sure the experiences here will help me in life.”

And yet, she plans to transfer.

Bennett, one of two all-women’s historically black colleges in the country, could be on the verge of closure. Years of financial woes have led recently to a federal court battle over its accreditation, without which the future of any college is dim.

Meanwhile, students like Hughes flee. Ten years ago, nearly 800 students roamed Bennett’s campus; now there are fewer than 500.

Bennett’s story reflects that of many of the nation’s 102 historically black colleges and universities, or HBCUs, most of which formed after the Civil War.

In recent years, the institutions overall have seen enrollments plummet, endowments decrease and student bodies — once entirely black — become more mixed as HBCUs attempt to compete with schools that no longer shut out African Americans.

Desegregation, along with a more recent push for diverse recruits among non-HBCUs and growing incomes among black families, has made historically black colleges and universities a less common option for African Americans.

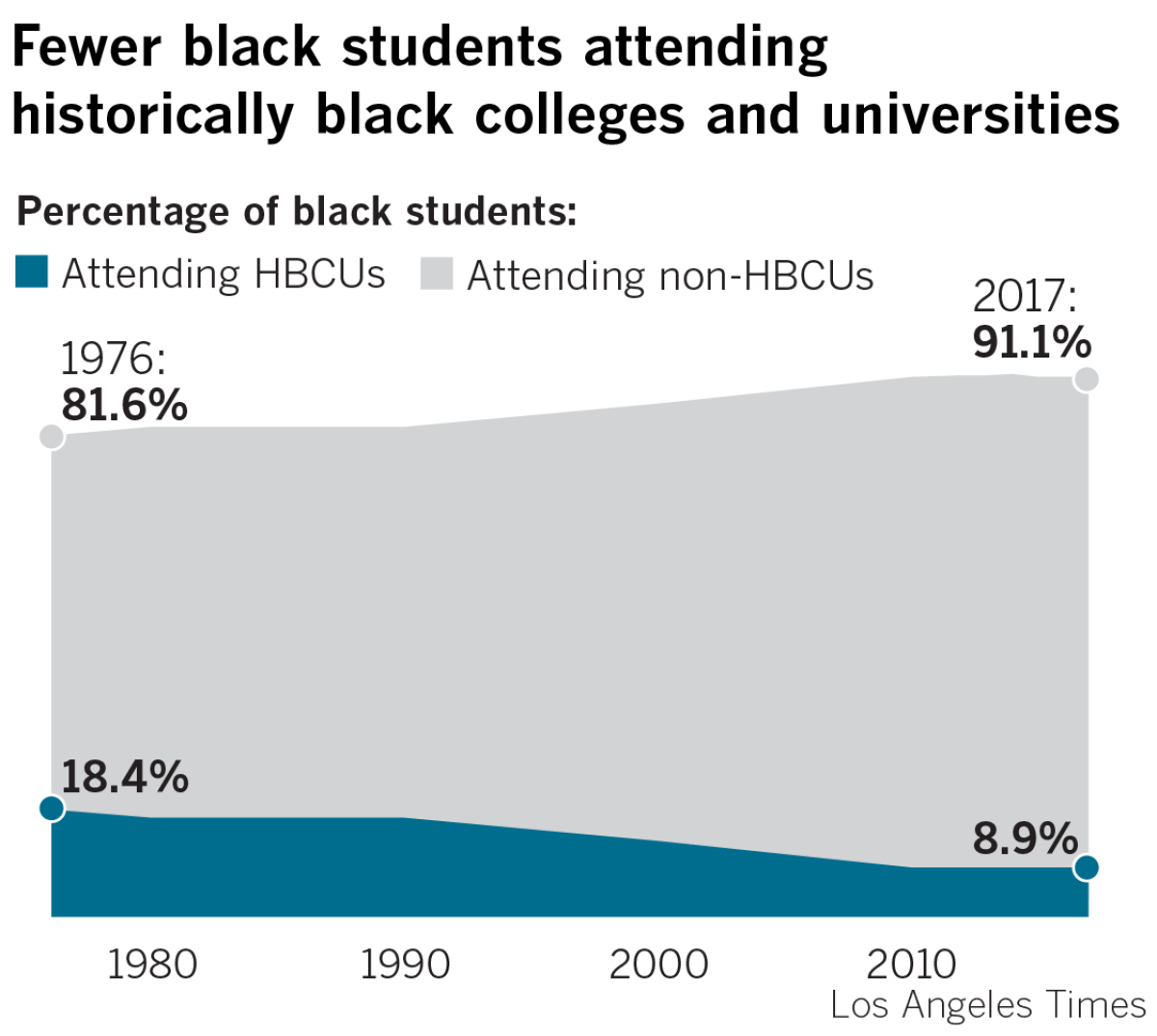

Fifty years ago, 90% of black postsecondary students attended historically black schools. In 1990, it was close to 17%. Today, around 9% do.

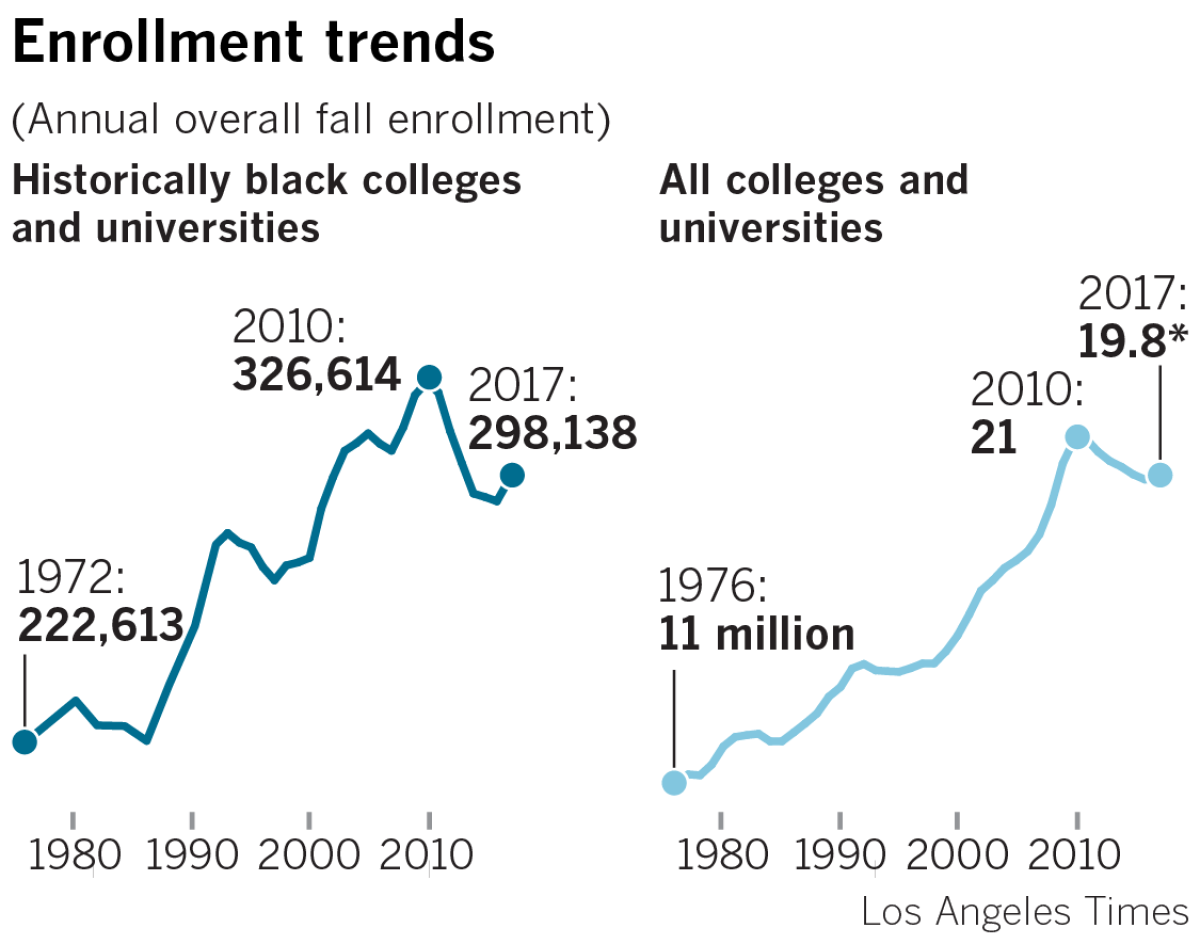

National enrollment reached a peak in 2010 at about 326,000. Today, it’s about 298,000.

The nation’s oldest historically black college, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania — founded in 1837 — has fought to keep its accreditation. It’s trying to raise at least $4 million to stay afloat. Three HBCUs have closed since 2000.

Other schools, including Alabama State University, Paine College in Georgia and Elizabeth City State University in North Carolina, have battled steep enrollment declines and major financial struggles. The same issues have led more than a quarter of the nation’s historically black schools to be put under warning or on probation by accrediting groups in the last decade.

“The situation of HBCUs is precarious,” said Crystal deGregory, a professor who studies their history at Kentucky State University, a historically black college in the state capital, Frankfort. “We don’t know if we’re going to make it.”

We asked for your experiences at historically black colleges. These are your stories »

Not all HBCUs have suffered. The most prestigious have thrived in recent years, with enrollment and endowments growing along with donations from well-known alumni.

“Everybody has heard of Howard, Spelman, Hampton, Morehouse,” said Dianne Suber, former president of tiny St. Augustine’s University in Raleigh, N.C. “But so many others are out there just existing day-to-day, check-to-check or sometimes worse.”

After their establishment, historically black colleges grew in size and influence for more than a century. Many of the oldest are private schools created by churches. Public campuses blossomed in the late 19th century. That’s when a federal law that granted land for universities also required states that barred blacks from institutions of higher education to create separate campuses to serve African Americans.

The schools have educated legions of black artists, business leaders and politicians. Spike Lee attended Morehouse. Oprah Winfrey went to Tennessee State. Jesse Jackson graduated from North Carolina A&T. Thurgood Marshall had degrees from Lincoln and Howard.

Bennett College was founded in 1873 as a co-ed institution in central North Carolina. In the 1920s, it became an all-women’s college, albeit one run by men. That changed in 1955, when Willa Beatrice Player became its president — the first black woman in the nation to lead a four-year accredited liberal arts college.

The campus is a five-minute drive from downtown Greensboro, where in 1960, four students from nearby North Carolina A&T University staged a sit-in at the whites-only Woolworth’s lunch counter. Dozens of women from Bennett joined the sit-ins, which stretched on for months and became among the best-known protests of the civil rights movement.

‘There is a correlation between atmosphere, retention and success at HBCUs.’

— Janelle Williams, visiting scholar at the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions

Black students tend to do better overall at historically black colleges, studies have shown.

“There is a correlation between atmosphere, retention and success at HBCUs” compared with how black students fare at other schools, said Janelle Williams, a visiting scholar at the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions at the University of Pennsylvania.

A study released last year by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Massachusetts at Boston also found that black students at HBCUs were more likely to graduate within six years than black students at predominantly white institutions. Black students at HBCUs are more likely to go on to graduate school than those who attend other schools, Williams said.

One advantage that historically black college students have is that their schools tend to be small; more than half have 2,500 or fewer students. But the size has also made financial and enrollment dips harder to manage.

In the last decade, HBCUs have increasingly recruited students who are not black, offering scholarships and touting their small class sizes and role in the fight for racial equality. At a quarter of the schools, non-black students make up at least 20% of enrollment today.

At Bennett, which graduated its first white student in 1960 — a civil rights activist who was part of the lunch-counter sit-in — white students make up a tiny minority.

‘I wanted the experience — at least for my education — to be one that is exclusively black.’

— Pilar Hughes, Bennett College student

Hughes, 19, grew up in New Jersey and had never lived outside the Northeast. After attending a mostly white high school, she wanted an all-black education.

“When else in life will you be able to be in an all-black setting working toward a common goal — getting a degree? That was a question I thought about a lot before deciding on Bennett,” she said, noting that a predominantly white institution — which is commonly referred to on campus by the acronym PWI — was never an option.

“The country is run by white people,” Hughes said. “I wanted the experience — at least for my education — to be one that is exclusively black.”

Hughes arrived in August. Four months later, as the struggles of the college became clear, she made a painful decision: She needed to transfer.

“Having a degree from an unaccredited — or potentially unaccredited — university makes no sense,” Hughes said.

On a recent morning, the biology major dropped by the enrollment management center to get her transcripts. She plans to apply to North Carolina A&T.

“I love this campus and these people. But the issues this school faces could hurt my future.… I have to move on.”

‘It would be upsetting to see my potential alma mater no longer in existence.’

— Abigail Mosley, Bennett College student

Abigail Mosley grew up in the suburbs of Cleveland and knew from an early age that she wanted to enroll at a historically black college or university. She’d felt stunted at her predominantly white high school, especially when learning about black history.

“Everything is narrated through a white lens,” the 21-year-old said.

She earned an associate’s degree near home, and last spring started looking at four-year colleges. Mosley was admitted to Spelman — the only other women's HBCU — but the Atlanta college didn’t offer her enough scholarship money.

While visiting colleges in North Carolina, she spent an afternoon at Bennett with her parents. They walked between the two- and three-story red brick buildings with bright white trim, where every class and dorm is within a 10-minute stroll. Knotty magnolias created patches of shade, and the calm of the small campus put her at ease.

“Immediately, I knew I wanted to attend,” Mosley said. “I can text my professors … there is investment in students from faculty.”

But Mosley recently applied and was accepted to Cleveland State University, a non-HBCU that’s closer to home.

“I have to have a backup plan,” she said. Once she gets her degree in political science, she wants to start a nonprofit in Cleveland that focuses on community organizing.

“It’s all up in the air right now,” Mosley said. “It would be upsetting to see my potential alma mater no longer in existence.”

In recent months, after going public with its accreditation struggle, Bennett netted more than $9.5 million in donations. Its accreditor, the Southern Assn. of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, nonetheless said Bennett was in financial trouble and took away its status. Accreditation allows colleges to offer Pell Grants, federally guaranteed loans and work-study programs, and make a degree more valuable.

The school had borrowed tens of millions from the federal government since 2001 for new construction, upkeep and refinancing, and it was in the red by more than $1 million in 2017. Last year, it was one of eight historically black colleges that were given six-year interest-free deferments on federal loans.

But school administrators, pointing to a budget surplus of $461,000 last year and the fundraising success, say the campus is on the mend. Bennett sued over its accreditation status, and in February, it won a temporary reprieve while the case proceeds.

There are bits of good news in Greensboro and for historically black schools, though. Nationwide enrollment, after hitting a 15-year low in 2016, increased by 2% in 2017. The jump came as overall enrollment in the U.S. fell. At Bennett College, enrollment grew more than 15% this year, to 471.

Some see the bump as reflecting young people applying to colleges in an era of increasing hate crimes and resurgent white supremacy. “Parents are rethinking what kind of environments students should be in for their education,” Suber said.

Bennett and other HBCUs were briefly in the spotlight after President Trump invited dozens of the schools’ presidents to the Oval Office the month after his inauguration. He vowed to make the institutions an “absolute priority” and later signed an executive order promising increased support.

Last year, the federal government forgave $322 million in loans to four historically black colleges in Louisiana and Mississippi that had borrowed money after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. In 2017, Congress approved the return of year-round Pell Grants, which can be used for summer classes; more than 70% of HBCU students receive the grants.

But some students and leaders now view the Oval Office visit as little more than a photo op.

As Bennett College’s future remains uncertain, some students have gone to the campus chapel to seek reassurance. They sit among white pews as light from narrow windows falls on a glass panel of a black Madonna.

“Students are concerned and are looking for answers,” the Rev. Natalie McLean said on a recent afternoon at the chapel.

McLean, 60, has spent 17 years as the school’s chaplain. She graduated from Bennett in 1980; her mother earned a degree from the school in 1954.

To McLean, the struggle of historically black colleges isn’t just about the future, but about remembering the past at schools that “provide unvarnished looks into history.” Beating the odds is what HBCUs are about, she said. McLean prays and is confident her school will survive the battle.

“We’re fragile,” she said, “yet fertile.”

Lee reported from Greensboro and Kaleem from Los Angeles.

Produced by Justin L. Abrotsky.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.