After Georgia veto of anti-gay bill, evangelical Christians feel betrayed

Reporting from ATLANTA — When Joshua McKoon learned that AT&T, Bank of America and hundreds of other companies had taken out a full-page newspaper advertisement to protest Georgia’s “religious liberty” bill, the Republican state senator took to Twitter.

“How grotesque,” he wrote.

The ad, which appeared Easter Sunday in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “sends a very clear message to the Christian community on where these corporations stand in respect to people of faith,” said the 37-year-old Catholic.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

To much of corporate America, the bill amounted to legalized discrimination against gay people by allowing them to be denied certain services and protections.

But to McKoon, he and other religious conservatives are the ones under assault as the country moves to the left on social issues. Even with Republicans controlling both chambers of the Georgia Legislature, as well as the governor’s office, they increasingly feel that their voices are being ignored.

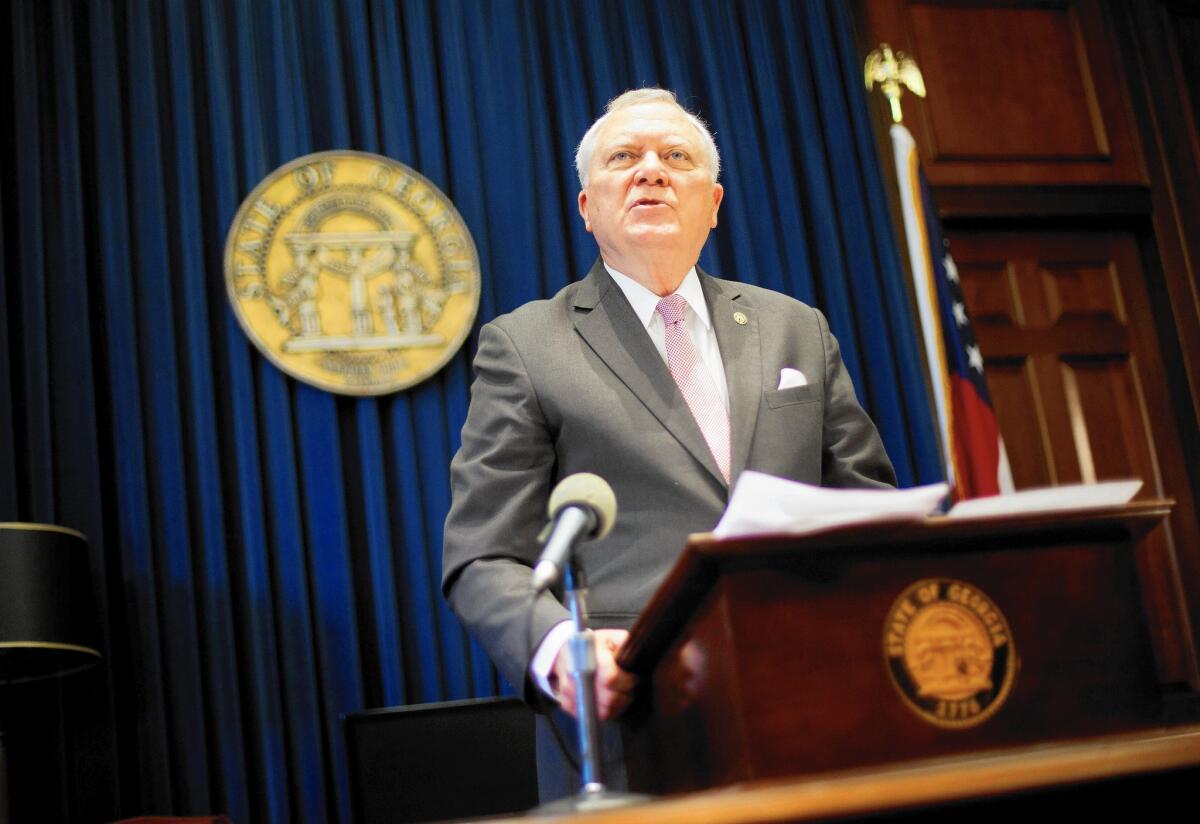

Their fears seemed to be confirmed Monday when Gov. Nathan Deal announced he was vetoing the bill, known as the Free Exercise Protection Act.

Religious conservatives still play a major role in American politics, with evangelical Christians holding steady over the last decade or so at just over a quarter of the U.S. adult population. In Georgia, that figure is 38%, according to the Pew Research Center.

Their power was on display when the Georgia Legislature approved the bill this month. Only 10 of 157 Republican lawmakers voted against it.

But as major corporations began their protest and entertainment industry powerhouses threatened to stop film production in Georgia if the bill was signed into law, moderate conservatives began to fear that the legislation could cost the state billions of dollars.

Only California and New York have more television and movie production than Georgia, which has lured Hollywood with tax breaks and cheap labor costs.

The governor said he could see no compelling need for the bill. His veto sent a clear message to many religious conservatives: Economic considerations carry more weight than the will of rank-and-file voters.

“This is a prime example of why Republicans across the nation are concerned and upset,” said Don Hattaway, 51, senior pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Church in Cartersville in north Georgia. “We vote for politicians according to what they say, and then when they get in office they do the contrary. It’s come to the point in Georgia that we don’t know who to trust.”

The bill would have ensured that a pastor could not be forced to perform a same-sex wedding and that nonprofit faith-based organizations could legally refuse to rent or lease property for events they found objectionable. It also would have given such groups the right to fire or not hire people whose practices they opposed on religious grounds.

Though critics pounced on the bill as discriminatory, its proponents said they merely wanted to provide people of religious faith with modest protection from mounting pressure to accept gay marriage.

“We simply want to act out our faith,” Hattaway said. “We don’t want to harm anyone. We minister to people and we feed the hungry, and we don’t ask what lifestyle people are living. But we also don’t want people telling us to embrace a lifestyle that is clearly immoral and denounced in Scripture.”

“A lot of people feel betrayed” by the veto, he said. “If a Republican governor, put in office by people who are conservative, Bible-believing Christians, can’t stand boldly and protect our basic liberties, I think we are all threatened.”

He and other Christian conservatives said their religious liberties were increasingly being put at risk by a series of legal decisions over the last decade, culminating with the Supreme Court’s ruling last year legalizing same-sex marriage.

They have reached the conclusion that their political power has been waning despite their sheer numbers.

“There’s a growing sense that we’re a majority whose rights and freedoms are being trampled upon,” said Mike Stone, 45, senior pastor of Emmanuel Baptist Church in the south Georgia town of Blackshear.

“I’m tired of politicians treating the church as a mistress,” he said. “They come round every two years when they need an itch scratched, but they’re not willing to make a long-term commitment.”

The biggest threat to the religious agenda is that American society as a whole is changing.

Even in conservative Georgia, attitudes toward gay marriage have become significantly more liberal. In 2004, 76% of Georgia voters approved a referendum to prohibit gay marriage.

Today, Georgians are essentially equally divided on the issue, according to a poll by the Public Religion Research Institute. It also found that about two-thirds of Georgians want laws to protect gays and lesbians from discrimination in employment, housing and public services.

Tom Taylor, a pro-business Republican state representative in the affluent Atlanta suburb of Dunwoody, said the shift was driven in part by people moving to Atlanta from other states.

“I think you’re going to see a lot more growth of the more moderate folks within the Republican Party,” said Taylor, who voted against the religious freedom bill. “There’s always going to be the squeaky wheel that’s in front of the camera, but they might not represent the views of the entire state.”

Jenny Jarvie is a special correspondent.

ALSO

North Carolina’s attorney general says he won’t defend transgender law in court

Some call it religious freedom, others call it anti-gay. Here’s a look at the battle in some states

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.