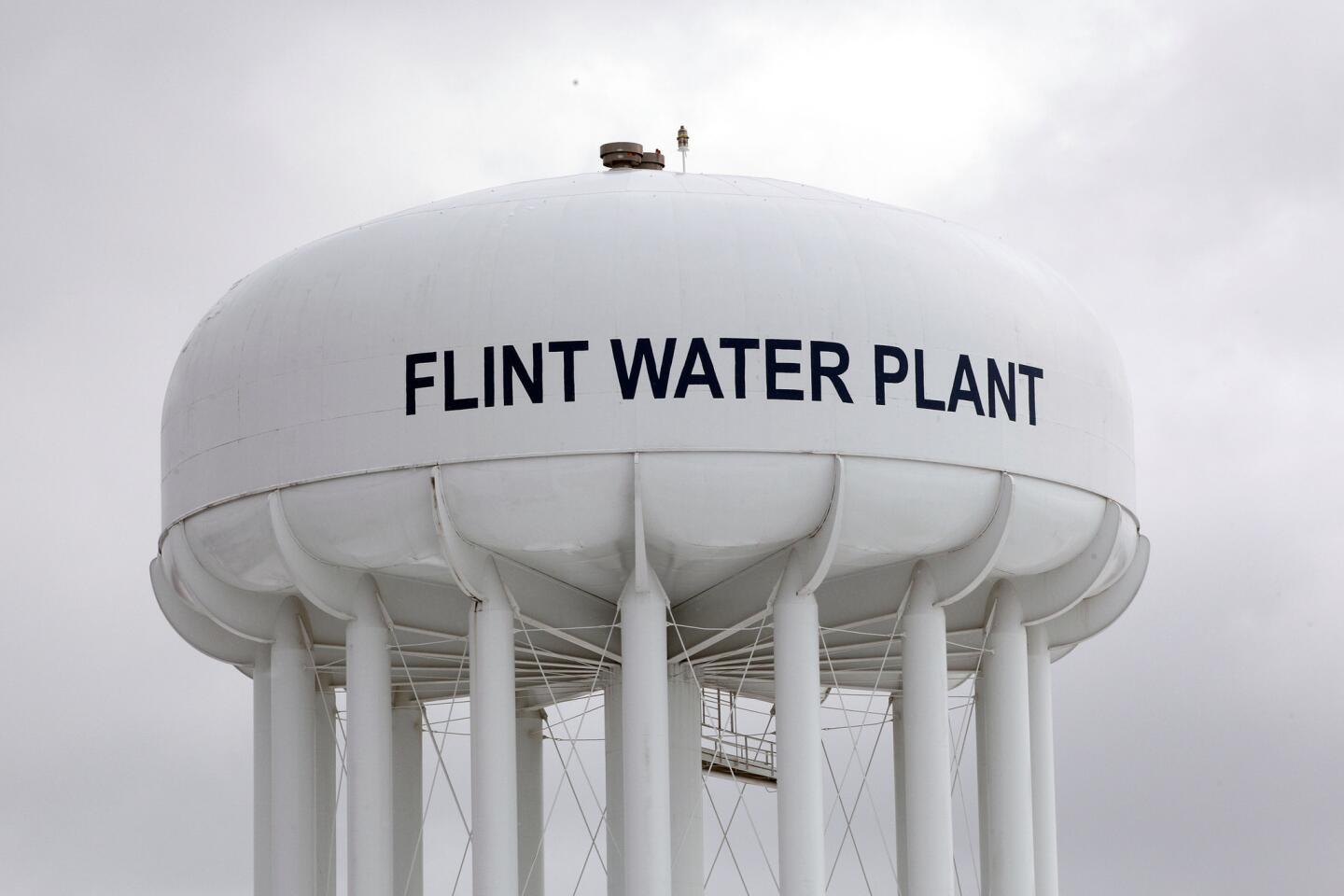

Michigan governor seeks federal disaster declaration in Flint water crisis

Reporting from FLINT, Mich. — Under steel gray skies, emergency volunteers dodged ice and snowdrifts as they made their way along the streets of the neighborhood of Mott Park, handing out free bottled water and filters from a U-Haul truck with a sheriff’s escort.

At each doorstep, the message was the same — please don’t drink unfiltered tap water.

Sam Berry, a 29-year-old pipe fitter wearing a Carhartt work coat and camouflage hunting boots, was halfway to his pickup in the driveway when a volunteer intercepted him, thrusting a case of water into his arms.

Berry was grateful. For weeks, he and others in this aging industrial city have lived with the worry that their drinking water has been contaminated with lead. Health officials are warning that routine things like bathing their children and brewing a cup of coffee constitute a risk.

“I don’t know what Flint’s going to do,” Berry said. “They’re trying so hard to turn this town around, but who wants water like this?”

Gov. Rick Snyder late Thursday asked President Obama to declare a major disaster in Genesee County and expedite federal aid to citizens affected by the polluted water supply.

“We are utilizing all state resources to ensure Flint residents have access to clean and safe drinking water, and today I am asking President Obama to provide additional resources as our recovery efforts continue,” Snyder said in a statement.

The governor also mobilized the Michigan National Guard, which on Friday was to begin distributing water and water filters and testing kits.

On the ground in Flint, Mich.

The water crisis is only the latest, and worst, to befall this city.

Battered by a tough economy — its fortunes rising and falling along with the auto industry — Flint over the last four decades has withered to a city of 100,000, its streetscape dotted with abandoned houses, its decline documented by filmmaker Michael Moore, a native son. About 40% of its residents live below the poverty line.

Berry was among those determined to tough it out and raise his 8-month-old son, Micah, in this tree-shaded working-class neighborhood of neat lawns and enclosed front porches.

But then the water went bad.

To save money, the state — which has been running Flint’s financial affairs — gave up on drawing the city’s drinking water supply from Lake Huron and instead began pumping it out of the Flint River, an industrialized waterway with a reputation for filth.

The switch was only supposed to last about two years, until a new state-run line connected to the lake.

Residents immediately noticed a difference in the water, which proved highly corrosive: 19 times more than Lake Huron water, according to researchers from Virginia Tech who tested the water last summer.

We are treating it as a population-wide exposure. Everyone who’s on Flint water now should be using filtered water or bottled water.

— Jennifer Eisner, a spokeswoman for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

Some residents filed a class-action lawsuit alleging the water was corroding city pipes and leaching lead because the state wasn’t treating it with an anti-corrosive agent, a violation of federal law.

City and state officials tried to reassure residents that the water was safe. Former Mayor Dayne Walling even drank it on local TV. (He has since reversed his position.)

“They told us it was safe,” said Harold Harrington, business manager of the local plumbers and pipe fitters union who led a team of eight volunteers installing filters for the elderly and disabled Thursday.

Harrington said the river water had a distinctive fishy odor and officials should have known it was dangerous.

“When General Motors switched back to lake water because it was corroding the parts, that should have showed people” back in October 2014 that the river water was suspect, he said.

Berry was among those horrified. He’d bathed his son in the tap water. He’d used it to mix his son’s formula.

Last October, the city reverted to using the lake water, but researchers continued to detect low levels of lead because of the damaged pipes.

Volunteers from the United Auto Workers distribute bottled water and filters to residents of the Mott Park neighborhood of Flint, Mich.

The long-running effects weren’t clear. Blood tests now won’t necessarily show elevated lead levels for those exposed during the last 18 months, said Jennifer Eisner, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Health and Human Services.

“We are treating it as a population-wide exposure. Everyone who’s on Flint water now should be using filtered water or bottled water,” she said.

The number of cases of Legionnaires’ disease has soared in surrounding Genesee County in the last two years: 87 cases, including 10 deaths, compared with six to 10 cases on average annually in the county. So far, the recent increase cannot necessarily be attributed to changes in the water supply, in part because some of those who fell ill were not exposed to Flint water, according to Dr. Eden Wells, the chief medical executive for the Department of Health and Human Services.

The state Department of Environmental Quality is evaluating the Flint water system now to see “what part of the plumbing would need to be addressed,” according to department spokeswoman Melanie Brown.

On Thursday, more than 30 Michigan National Guard troops were prepared to help distribute drinking water and filters and offer other assistance; the American Red Cross has volunteers at five fire stations, two of which had been mothballed because of the city’s dwindling population.

Among the pipe fitters installing water filters Thursday was Marcus Eubanks, 34, a father of six. The schools are using bottled water, his children have had their blood tested with no sign of elevated lead levels, but he and his wife worry.

He’s still paying his water bill — $130 a month — although he said it hardly seemed fair. Some are calling for free water for the next six months, or free bottled water. Two of Eubanks’ cousins have moved, but he’s got three years of apprenticeship left.

“We’re trying to do the best we can until they get a permanent solution,” he said.

In Mott Park, volunteers delivered filters to Zakia Shaheed, 63, who said her 10-year-old grandson had elevated lead levels in his blood and had been prescribed medication.

A few streets over, they gave water to Kadija Bah, 29. Originally from Senegal, Bah said she has been fielding calls from friends and family across the country worried about her and her 6-month-old daughter, Miriam. Back in Senegal she had to avoid tap water. But, she said, “I would never have thought it would happen here.”

Down the block, Molly Panek, 43, a pharmacy technician who grew up in Flint, told volunteers she didn’t need water: her father had installed a pricey reverse osmosis filter system at her white frame house. Not everyone, she said, can afford to be so proactive.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“I love this city and I plan on staying here,” she said. “But I don’t like the idea that my neighbors are ill.”

Sheriff Robert Pickell said some officials have told him the pipes will fix themselves in a few months, but he doesn’t believe it. He urged state and federal officials to send more aid and resources to repair the pipes and assist the emergency response.

“People have lost faith in the capacity of the government to deal with the problem,” he said, as he watched volunteers shuffling by with cases of water. “It’s going to take a lot to gain that back.”

ALSO:

Oscars 2016: Here’s why the nominees are so white -- again

Chino Hills 7-Eleven still waiting for its Powerball winner to come forward

Tension between ranchers and federal officials is dangerously high in Nevada

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.