In Ferguson, a night of political theater, protest and peace

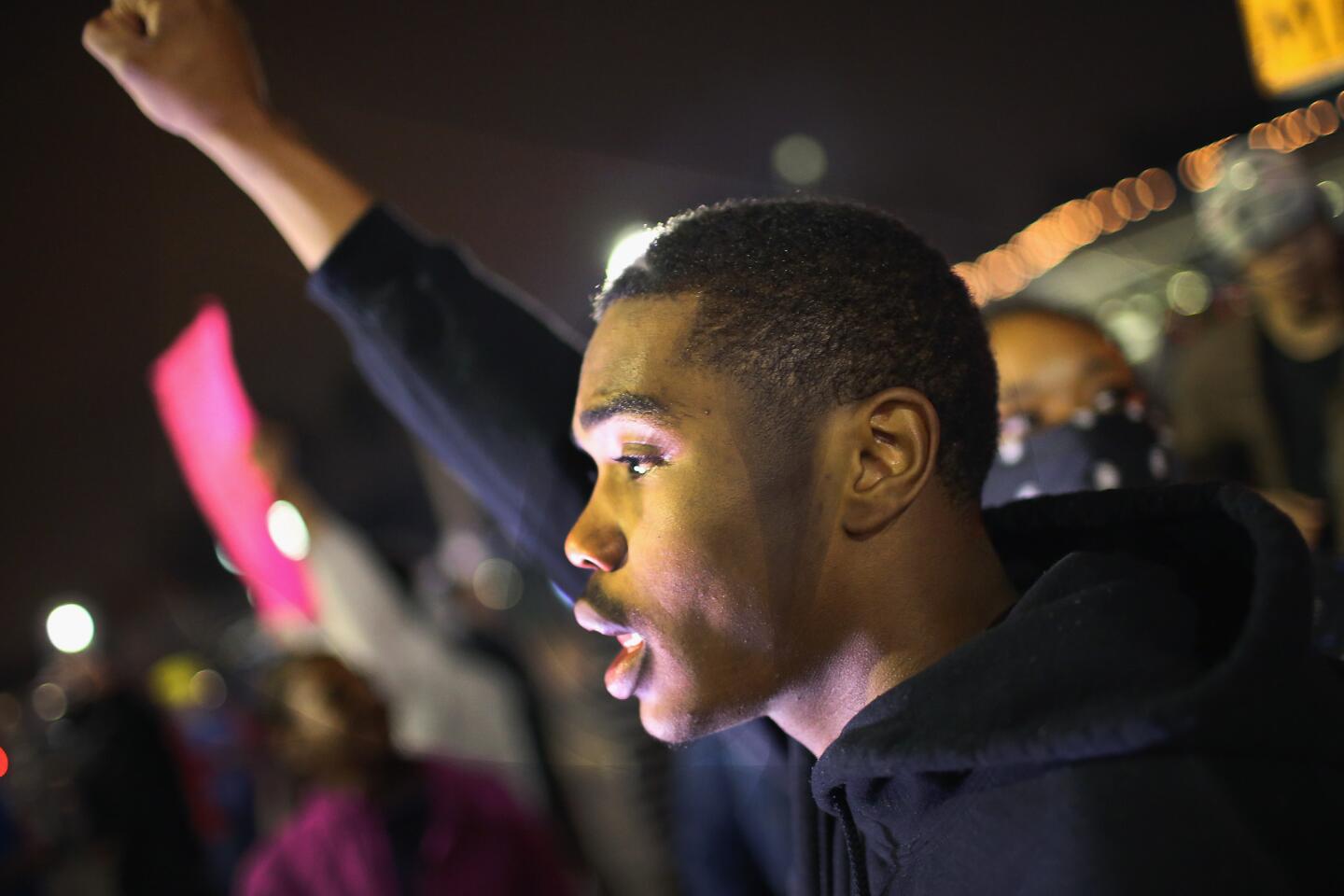

Reporting from Ferguson, Mo. — Facing off across the very spot where two St. Louis-area police officers were wounded by gunfire less than 24 hours earlier, police and protesters engaged in a long evening of stare-downs and posturing late Thursday.

A line of police officers stood next to or behind a row of white police vehicles for protection against possible gunshots. But they did not wear riot gear, and many stood openly just a few feet from where their comrades were shot in front of the low, brick Ferguson Police Department headquarters. Both are expected to recover.

A few dozen protesters wandered back and forth near the spot where the officers went down. At least as many journalists as demonstrators had gathered.

Early in the evening, a group of ministers held a prayer vigil in which they pleaded for non-violence and lit candles in honor of the two wounded officers, as well as for blacks killed by police. That included Michael Brown, the unarmed man whose killing last summer triggered unrest and longlasting protests.

Police officers, too, hoped for peace Thursday night.

St. Louis County Police Lt. Jerry Lohr, a buzz-cut officer with tobacco in his cheek, was in charge of the police response, along with an officer from the Missouri State Highway Patrol.

Ferguson residents call Lohr “Officer Friendly.” When they saw him, some protesters hugged him and shook his hand. They expressed concern for the two wounded men and said they didn’t want to see officers hurt.

He accepted their handshakes and reassurances, wearing, as he always does, a uniform without riot gear, and standing, as he always does, at ease instead of in lockstep.

That was a dramatic departure from the Ferguson police response of recent weeks and months. It was a return to the approach Lohr took when he was last sent to help with security here in October.

Lohr acknowledged at the start of the night that it was a tough time to try community policing.

“There is an added sense of unease due to the events of last night -- on both sides,” he said as he stood with fellow officers behind him, facing the chanting crowd.

“The spouses of the officers who came tonight are really worried,” Lohr said -- and that included his own wife.

Getting shot is always a possibility. Still, he said, officers were determined “to treat people as humans, with dignity.”

Some demonstrators said they feared being shot -- either by gunmen or police -- but walked openly on the street and sidewalk.

Protesters blocked all or parts of the street in front of the Ferguson Police Department. They greeted police requests to clear the street with chants, some of them profane. They pounded on drums and chanted as officers stood, arms folded.

Officers watched in silence at “standoff distance” -- farther from protesters, and in a less militaristic posture, than during previous confrontations. They stood next to where anti-police slogans had been scrawled in blue and pink chalk the night before. One read, “Racist police.”

This was a night of political theater. Sometimes police and protesters talked with one another, albeit briefly, as TV crews bore down on them.

Lohr, 41, waded into the crowd more than once, chatting with protesters and pleading with them to clear the streets. He was accompanied by a handful of officers wearing sidearms but no riot gear.

When a masked protester sat in the street and blocked a car, Lohr walked over and gently lifted him out of the way.

“Hey, partner, you can’t sit in front of a car,” Lohr told him.

The protester did not resist, and the small gathering of people blocking the edge of the street did not intervene.

Lohr, flanked by a handful of officers, walked back to the police parking lot, where other officers stood watching.

About 10 p.m., an officer announced through a bullhorn, “If you remain in the roadway, you will be subject to arrest.”

Some demonstrators hooted; most held their ground.

Lohr persuaded some protesters to move to the edge of the road so cars could pass. But when others stayed in the middle of the street, he shook his head and walked back to the parking lot.

“Well, A for effort, huh?” he said.

Kevin Nevels, 48, approached Lohr at the edge of the parking lot. He wore a small camouflage vest under his sweatshirt, and Lohr asked him why.

“I feel intimidated with your guys all standing there in formation,” Nevels told him.

Nevels, who is African-American, said he was afraid to walk or drive the streets of Ferguson lest he be shot by a police officer.

“These people don’t want to hurt you,” Nevels told Lohr. “We feel bad about what happened to those officers. But the people who shot them were up the hill, not part of who we are.”

Lohr nodded and said he was doing his best to keep the peace and maintain an open dialogue with the community. Nevels thanked him and retreated into the crowd.

“He was OK,” Nevels said of Lohr moments later. “But I felt like I was getting a lot of niceties, you know, the regular police talking points.”

About 10:30, some officers put on dark vests and helmets. The crowd chanted, “Why you got on riot gear? We don’t see no riot here!”

Later, officers began going indoors, until only a few remained. A light rain fell, and the protesters began to thin out.

By 11:30 p.m., the crowd was gone, the street was clear, and the police officers were back inside their headquarters. There had been no arrests.

Lohr stood in the light rain, leaning against a barrier and reflecting on the night’s events. Police made a conscious decision to be non-confrontational and to keep a “standoff’’ distance between officers and protesters, he said.

“The strategy was to protect peoples’ 1st Amendment rights to peacefully protest while also protecting these officers so that they can perform their jobs,’’ he said.

The shootings left officers shaken and anxious, Lohr said, but he added: “These are professional law enforcement officers. We’re all out here to conduct ourselves in a professional manner.’’

Because he had worked street protests in Ferguson in the past and knows some demonstrators by name, he said, he had “a level of comfort.’’ The shootings were on his mind -- and on every officer’s mind -- but he believed the best strategy was to stroll into the crowd and talk to protesters.

“I didn’t feel that the tone of this group was militant or antagonistic. It didn’t have that tone of violence,’’ he said.

The lieutenant paused and looked out at empty, rain-slicked streets that had been clogged with chanting protesters just an hour earlier.

“I think it went pretty well,’’ he said.

Twitter: @davidzucchino, @mollyhf

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.