In Ferguson, ‘Officer Friendly’ tries to ease tension on both sides

Reporting from Ferguson, Mo. — When Jerry Lohr left for work Thursday morning, his wife had a request — no, a demand. She insisted he pose for a photograph with his 14-year-old son.

Lohr didn’t have to ask why. Only hours earlier, the on-and-off street protests that have rocked the city of Ferguson since last summer had been shattered by gunfire. Two officers had been hit. Though neither sustained long-term injuries, it seemed certain that the St. Louis suburb was in for another day of demonstrations. No gunman had been identified. It felt like a night when anything could happen.

Lohr, a 14-year St. Louis County Police Department veteran who would be co-commanding police units on the street that day, headed out the door.

“There is an added sense of unease due to the events of last night — on both sides,” Lohr said as a small but growing crowd of demonstrators started chanting in the biting drizzle outside police headquarters.

It was the beginning of a long night of confrontation and conciliation for Lohr as he struggled to bridge the suspicions between the police officers under his command, mostly white, and the predominantly black crowd of protesters. His patience and resolve were tested as protesters shouted insults and TV cameras from around the world followed his every utterance.

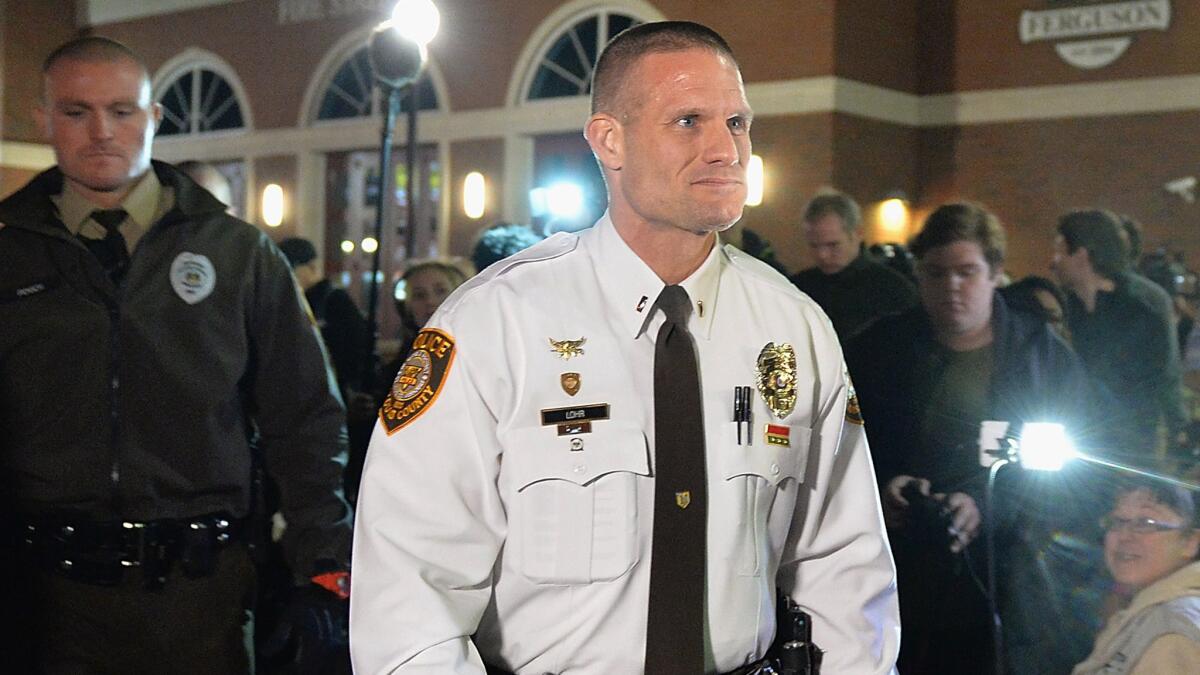

With his blond buzz cut, laconic speech and a wad of Copenhagen tobacco wedged in his cheek, the 41-year-old Tennessee native is often called “Officer Friendly” by locals. He set a deliberately low-key tone for what was going to be a long, chilly and nervous night.

Lohr advised his officers to show up, as he did, without riot gear. Taking a position in front of a line of officers — clustered this night behind the dubious shield of a row of police cars — Lohr showed them how to stand. Not at attention, but at ease.

“Our strategy [is] to avoid confrontation,” he explained.

“I’ve heard them say protesters are shooting at police — I don’t think that’s a fair statement,” he said. “That’s not to say there aren’t people out here tonight who don’t want to hurt us.”

This small Midwestern city has been the scene of rioting, looting and sporadic gunfire since the shooting in August of 18-year-old Michael Brown, an unarmed African American, by a white police officer.

Some of the tension had seemed to ease with a U.S. Justice Department report released last week that appeared to substantiate the complaints of many black citizens about racial bias in the Ferguson Police Department. The police chief, the city manager, the court clerk and the town’s only municipal judge had all stepped down or were fired, along with two police officers found to have sent racist emails.

Then came the shootings shortly after midnight on Thursday, when one officer was hit in the shoulder and another in the face — and then, the next night, another round of protests. It was Lohr’s job to make sure things didn’t get worse.

Their goal, he announced, was “to treat people as humans, with dignity.”

As the night wore on, it was clear that both sides were making an effort to step back from the brink.

A group of ministers was working a few blocks down the road to unify police and protesters in shared loss. They prayed for Brown, and also for the wounded officers.

“We come to curse those who fire shots in the darkness,” the Rev. Starsky Wilson said as protesters banged drums and shouted slogans nearby in a nightlong pas de deux in front of police headquarters. “We ask you, Lord, to be with these police officers who have suffered injustice and put them back up on their feet.”

The Rev. Traci Blackmon led another prayer. “We’ll not be derailed in the pursuit of justice. We will not stop,” she declared.

But then she spoke to the crowd: “Hug somebody and go home.”

Lohr made his way through the throng as chants thundered out through the mist.

“The whole damn system is guilty as hell!” said one. “We don’t need no racist cops!”

Lohr told demonstrators they had the right to protest, but they couldn’t block the streets. Over and over, he’d gently ask people to let traffic pass. Some obeyed. Most didn’t.

When one protester sat down to block a passing car, Lohr gently lifted the young man off the pavement. “Hey, partner, you can’t sit in front of the car,” he said. The man complied, and no one challenged the lieutenant.

Several people emerged from the crowd to hug Lohr or shake his hand, remembering him from October, when he was previously sent to Ferguson to help with security.

“How ya doin’?” Lohr would say, shaking hands.

With the shootings weighing heavily on his mind, Lohr told his officers that their best bet was to stay back behind the line of police cars. “Standoff distance tends to alleviate some of that pressure,” Lohr said. “It’s kind of hard to shout at someone from 30 feet away.”

In the tense standoffs that have made this city a national symbol of racial tension, there are some who have managed to stand between black and white, police and community. They have found themselves navigating a difficult and ambiguous terrain.

Sometimes it’s the local ministers, who calmed tempers Thursday night with their candlelight service. Earlier last year, it was Capt. Ronald Johnson, an easygoing black Missouri highway patrol officer who calmed crowds. On Thursday, it was a white cop from Nashville who looked and sounded more like a country and western crooner than a tough riot cop.

Lohr’s officers were anxious, and it was his job to protect them. But the safety of the often rowdy crowd was also in his hands.

Every step, he admitted, was shadowed by the thought that perhaps the unknown shooter or shooters were hiding in the crowd, or in a sniper’s perch nearby. Lohr strolled past yellow police tape and mingled with the crowd in his starched khaki uniform. He wore a handgun in a secured holster.

“As a police officer, you never feel totally safe,” he said. “I put on a bulletproof vest every day not because it’s comfortable, but because it’s part of the job.”

It’s worse for those who wait at home for an officer’s safe return, he said. “The spouses of the officers who came tonight are really worried,” he said.

One protester, Kevin Nevels, 48, wore a small, camouflage armored vest under his sweatshirt. But he also engaged Lohr in a spirited conversation about fears, racial assumptions and policing.

Lohr asked him why he was wearing a vest, and listened patiently to Nevels’ loud discourse on his fear of being killed by police while walking or driving through Ferguson.

Just before midnight, as a steady drizzle fell and the protests fizzled out, Lohr seemed weary but relieved.

He called the police shootings “an ugly reminder that there are people out there who want to hurt the police.” He added: “You can’t assume everybody you see is out to get you, but you have to remain constantly vigilant.”

On this night, he and his officers were watchful but restrained. The protesters screamed slogans and blocked traffic, but ultimately decided to call it a night.

The officers were allowed to leave their posts, filing off into the police station. Lohr went home to his wife and son.

“Things worked out tonight,” he said. “We didn’t have to make arrests, and nobody got hurt.”

For news from Ferguson, Mo., and across the country, follow @davidzucchino and @mollyhf on Twitter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.