At a Ferguson shop damaged again, owner cleans up and perseveres

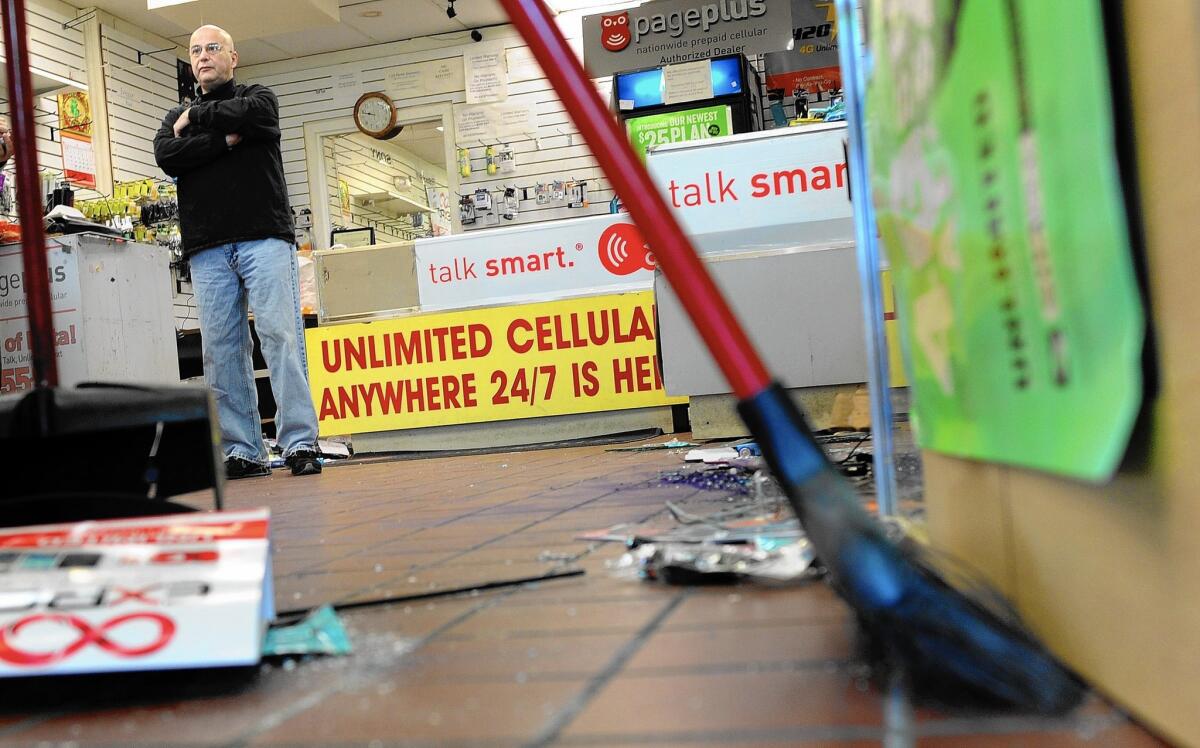

Reporting from Ferguson, Mo. — Here was the worst moment in Sonny Dayan’s riot nightmare: He stood inside his cellular phone store, surveying the damage to the business he opened because people encouraged him to take a chance on Ferguson.

The big storefront windows of STL Cordless had been shattered. Glass littered the floor along with the debris left behind when intruders stormed in Monday night, ransacking its shelves of phones and accessories. A cash register too.

Just across West Florissant Avenue, several structures were in flames. Oily black smoke wafted into Dayan’s store, so thick it blocked out the lights and made him cough.

It was just a small part of the spasm of violence that pulsed through this St. Louis suburb after a grand jury decided Monday not to indict Ferguson policeman Darren Wilson in the August shooting of Michael Brown.

And there stood Dayan in the middle of it all, a struggling businessman who had taken a real risk nearly two decades ago to open a shop in an area racked by homicide, robbery and violence — someone who doesn’t look back, who says he’d do it again if given the chance.

The 53-year-old immigrant from Israel held two cellphones to his head, one to each ear.

“People were calling — they were worried about me,” he said Tuesday, recalling the night before. “My wife, my friends, my customers.”

Nearby businesses had boarded up their windows last week in anticipation of the grand jury announcement. But Dayan stood strong. People he considered loyal clients needed phones. And he was going to be there.

This loyalty came even though Dayan’s store was looted months ago in another eruption of public anger following the Brown shooting Aug. 9. After that, Dayan cleaned up and reopened. And he stayed open, as the storm clouds of rage collected on the horizon.

As Monday night turned into Tuesday morning, buildings burned and sirens wailed and the sound of gunshots continued.

The bright moment in Dayan’s riot aftermath came just after noon Tuesday. The West Florissant Avenue commercial drag had been closed overnight as investigators canvassed the burned-out shells of buildings that were now considered crime scenes. Some that had not burned had been looted.

The police had decided to let business owners inside the barricade to check their stores. Dayan showed up in a black shirt and blue jeans, topped by a green wind breaker with a shamrock on the chest. His head was shaved.

He walked up to a group of African Americans watching police stop traffic. Here was a white man in a mostly black neighborhood amid the morning hangover of the previous night’s destruction. The reception could have been tense.

Instead, it was joyous.

“Yo, Sonny!” One man called out, stepping forward to wrap the diminutive Dayan in an emotional embrace. “You’re back!”

Several waited their turn to slap his back and offer regrets over his losses.

“Sonny is like family — he’s a real good friend,” said Kapeli Wiggins, whom Dayan often gives odd jobs around the shop so he can earn some spending money. “The people who did this did not know Sonny. If they did, they would have let him be. Sonny’s a good man.”

The police allowed Dayan and two men to cross the deserted four-lane road that would usually be teeming with cars at this time of day. Dayan put the key in the lock to his shop like he always does, even though the windows were gone.

“OK, guys, this is what we need to do,” Dayan started. The coat was off. The shop owner’s game face was on. Just Sonny, taking charge. Like always.

As it did the night before, his cellphone rang again and again. People calling about his welfare. Meanwhile, the men went to work sweeping glass.

Wiggins stared into a pile of trash. “Like, what do you get out of this, attacking a hard-working man’s business like this?” he said. “What do you gain? You want to strike out at the establishment? Go knock out a bank window. Leave this good man alone.”

In the days leading up to the riots, Wiggins said, he and other friends of Dayan pleaded with him to throw some boards over his windows, just to be safe. After all, some thugs had looted him in August, causing $15,000 in damage. Why not figure they’d do it again?

“But Sonny said he didn’t want that,” Wiggins continued. “He’s the boss. And what the boss says goes.”

Wiggins worked while he talked. Within minutes, he’d cleaned a major portion of the floor. Finally off the phone, Dayan approached him and tried to take the broom from his hands, telling Wiggins he had done enough.

“Thank you, thank you,” Dayan said.

“Please,” Wiggins said, smiling. “You’re Sonny.”

Wiggins kept sweeping.

Dayan was born in Israel and emigrated to the U.S. in the 1980s. He lived in Los Angeles, New York and Las Vegas before moving to St. Louis to be with the woman who would become his wife.

He opened his first phone store in St. Louis in the early 1990s, when pagers suddenly became the rage. Many of his African American customers lived in nearby Ferguson, and they eventually began trying to coax him to open a store in their town.

Several men even scouted out a place, the site of an old pizza parlor. Dayan came by one day and liked what he saw. That was 18 years ago.

Over that time, violence surged, even before Michael Brown’s death. He’s been looted and robbed. Each time, he cleans up and moves on. He worries that some bigger companies with outlets here will be scared away by Monday’s riots.

He winced at the suggestion that an African American community nearly burned itself to the ground the night before. “I don’t think this represents who we are in Ferguson,” he said. “There are a lot of good folks here who want nice places, nice shops, just like any community.”

But Dayan has learned a lesson. On Monday night, moments before the grand jury’s decision was announced, he closed his shop and prepared to leave. He looked outside and saw several young teenagers — maybe 13 years old — loitering outside. One had a handgun he was spinning in his palm.

Dayan thought about calling the police, but didn’t. No need to draw attention to his shop and his neighborhood on a night like this. “Driving home I had this ‘here it comes again’ feeling in my stomach,” he said. “But I still had faith.”

He returned hours later to the glass-littered floor, the smoke blocking out the light.

But as always, Dayan is going to clean up and move on. As he supervised the cleanup Tuesday, his wife called.

“She doesn’t want me to be down here,” he said. “But here I am. I’ve got a business to run.”

He’s not even reporting the losses to his insurance company, for fear his policy will be canceled, that they’ll give up on him.

But Dayan isn’t giving up on Ferguson.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.