Ferguson protests lure many from across the U.S.

Reporting from FERGUSON, Mo. — Illai Kenney, a telecommunications student in Washington, found herself mesmerized by the constant stream of images flooding into her Twitter feed of protests underway in the small town of Ferguson, half a continent away.

Pictures of women whose eyes were swollen from tear gas. A mother’s anguished weeping. Hundreds of citizens marching through the streets, their hands held aloft in defiance of a police force that had killed an unarmed young black man. She knew one thing: She had to be there.

Kenney quickly packed a bag, got in a car with friends and drove 1,300 miles west along Interstate 70 to Ferguson.

“This is a movement. To see why these people — my people — were marching on the streets was just too much for me to just watch,” said Kenney, 25, who is black.

West Florissant Avenue — ground zero for the demonstrations in the aftermath of the shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown on Aug. 9 — has exerted a powerful pull across the country.

The protesters — old and young, black and white — have been drawn here in large numbers since Brown’s death. They are idealists and activists, opportunists and agitators.

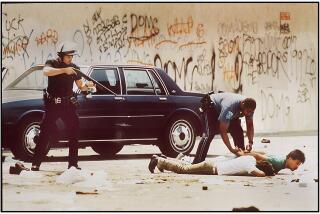

After 10 days of chaotic demonstrations, law enforcement officials have marked outsiders as the root of the continuing nightly unrest.

Capt. Ronald Johnson of the Missouri State Highway Patrol, who was put in charge of security during the demonstrations in Ferguson, said his officers had come under fire from armed agitators. Dozens of demonstrators, some having come from New York and California, have been arrested for refusing to disperse or looting.

“This was not an act of protesters,” Johnson said Monday. “This was an act of violent criminals.”

But out of the myriad reasons that people from outside the area have traveled here, they are joined by the awareness that this is a distinct moment in time.

The world is listening to the sound of chanting on the streets of Ferguson. The world is watching hands up in the air and tear gas arcing above.

“I need to be here, I want to be here, so I can be a part of some kind of justice,” Kenney said.

Far from the protests on West Florissant Avenue, the Knights Inn Ferguson is usually not too busy this time of year. It’s a neat motel by the side of Interstate 270 that caters more to local customers.

Raj Bhakta, an employee, said the motel had seen an uptick in business since the protests in Ferguson began.

“We usually don’t have out-of-town business, but we have seen more people,” Bhakta said.

How many people have come to the area is unknown, but law enforcement officials say it has been a significant number.

They have been drawn to an unlikely center of protest: a milelong stretch of West Florissant Avenue, dotted with auto supply stores, Chinese take-out places, gas stations and liquor stores.

It is a fast, four-lane thoroughfare that caters more to the stream of cars than to the people who live nearby. Few trees offer shade to anyone walking past.

Just a few hundred yards east, along Canfield Drive, is where Brown was shot in front of the apartment building where he was staying.

The next day, protests erupted along West Florissant, centered on the QuikTrip gas station and convenience store. It was quickly looted and burned.

On ensuing nights, the protests would move south along the avenue to the McDonald’s, where plumes of tear gas would rise into the sky as police tried to disperse the crowds.

Mickey Ilueberry and Jessica Luby, roommates in Minneapolis, were drawn by their outrage at the tear gas.

“We were absolutely horrified,” said Ilueberry, 24, a student at Metropolitan State University in Minneapolis.

She had never taken part in protests, but this was different. “It was me,” Ilueberry, who is also black, said, holding her hand over her heart. “It involved brown people, black people. This is our movement. It affects us. I had to be a part of it.”

Ilueberry, Luby and a third friend piled into their car and drove nine hours to Ferguson, arriving about midnight Monday as protesters were again facing down lines of tense police.

Unlike the few in the crowd hurling bottles and what police said were Molotov cocktails, the women say they did not come to stir up trouble. Rather, they are trying to raise money to provide equipment such as gas masks, food and water for demonstrators. Ilueberry said they had collected about $1,000 so far.

But they acknowledged that the more violent outsider element had been problematic and worried that that was deflecting attention from what they see as the issue: the death of Michael Brown and other black men and women at the hands of police.

“Those anarchists are just angry and don’t know what to do with their anger,” Ilueberry said. “But it reflects badly on black people and on white people.”

Luby, 25, said the agitators were young people “who really want to be involved in something,” but their presence in the nightly crowds were a problem.

“It does worry me,” because it detracts from protesters’ complaints and concerns, said Luby, who is also a student.

“People are doing that,” she said of the hurling of bottles and other objects. “But we have to be able to stand firm.”

The women said they planned to stay until Thursday. Ilueberry said she would like to stay longer, but her classes resume Monday.

“I have all this passion,” she said. “Since I came here, I’ve never felt so comfortable. I’ve never felt so at home.”

Many pastors and politicians have used social media to highlight people from out of town who are in Ferguson causing havoc.

St. Louis Alderman Antonio French, who has gained popularity with protesters, posted a photo Tuesday on Twitter of a white male from Chicago in the crowd who he said was “trying to incite a riot.”

Dante Barry, deputy director of Million Hoodies Movement for Justice, which was formed in the aftermath of the 2012 shooting death of unarmed black Florida teenager Trayvon Martin, crammed into a sedan with four of his colleagues and traveled from New York to Ferguson.

“We can’t have people out here acting ignorant because it hurts the bigger message of needed change in the relationships that police have with blacks,” Barry said. “I hope people come to Ferguson for the right reasons, because the world’s eyes are on this city.”

Like Kenney, Romaine Walls, 29, of Minneapolis knew as soon as he heard about Brown’s shooting that he had to come to Ferguson.

His parents were from the town, but he had never been to Missouri. Walls, a barber, said he wanted to help, so he cleared his schedule for a week and caught a flight Monday to St. Louis.

“I’m just trying to be part of the movement in a positive way,” Walls said as he stood on West Florissant watching protesters march by Monday chanting, “Hands up, don’t shoot!”

Walls had written the slogan on a piece of poster board affixed to the windshield of his car along with a sign that read, “Justice for Mr. and Mrs. Brown.”

“I hope to just get the word out,” he said.

Twitter: @kurtisalee

Twitter: @tinasusman

Lee reported from Los Angeles and Susman from Ferguson. Times staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske in Ferguson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.