Violence erupts after grand jury declines to indict Ferguson officer

Reporting from Ferguson, Mo. — A grand jury on Monday declined to indict a white police officer in the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown, an unarmed black man, unleashing angry protests by demonstrators who said the outcome proved the justice system’s failure to value the lives of African Americans.

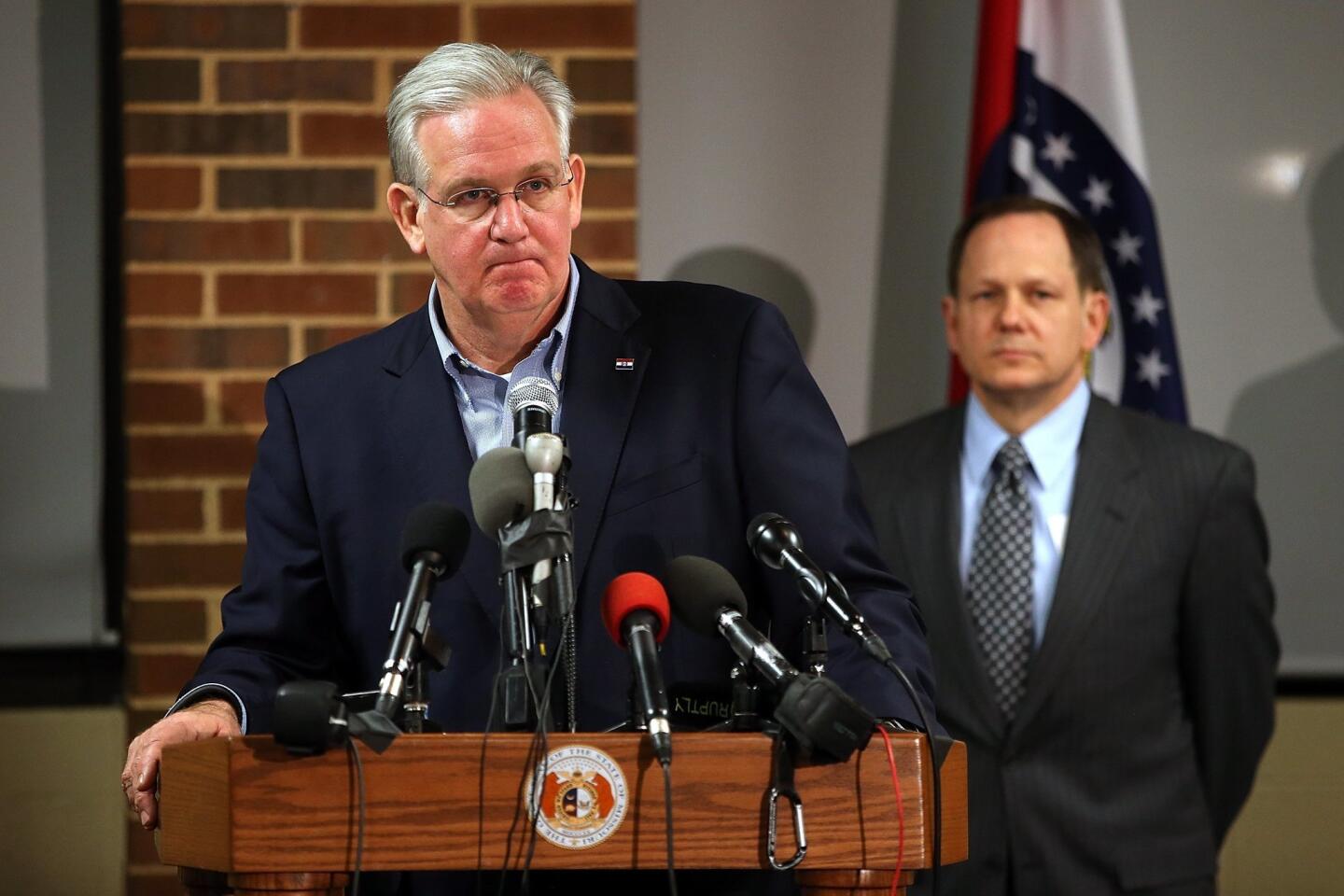

Brown’s death became a catalyst for anger, from the American heartland to the coasts. That anger boiled over quickly after St. Louis County Prosecuting Atty. Robert McCulloch said the jury of nine whites and three blacks had found no cause to file criminal charges.

The decision followed weeks of tense anticipation across the country and touched off demonstrations from New York to Los Angeles and Oakland, even as furious protesters in Ferguson set fire to buildings and police cars and stormed into shops.

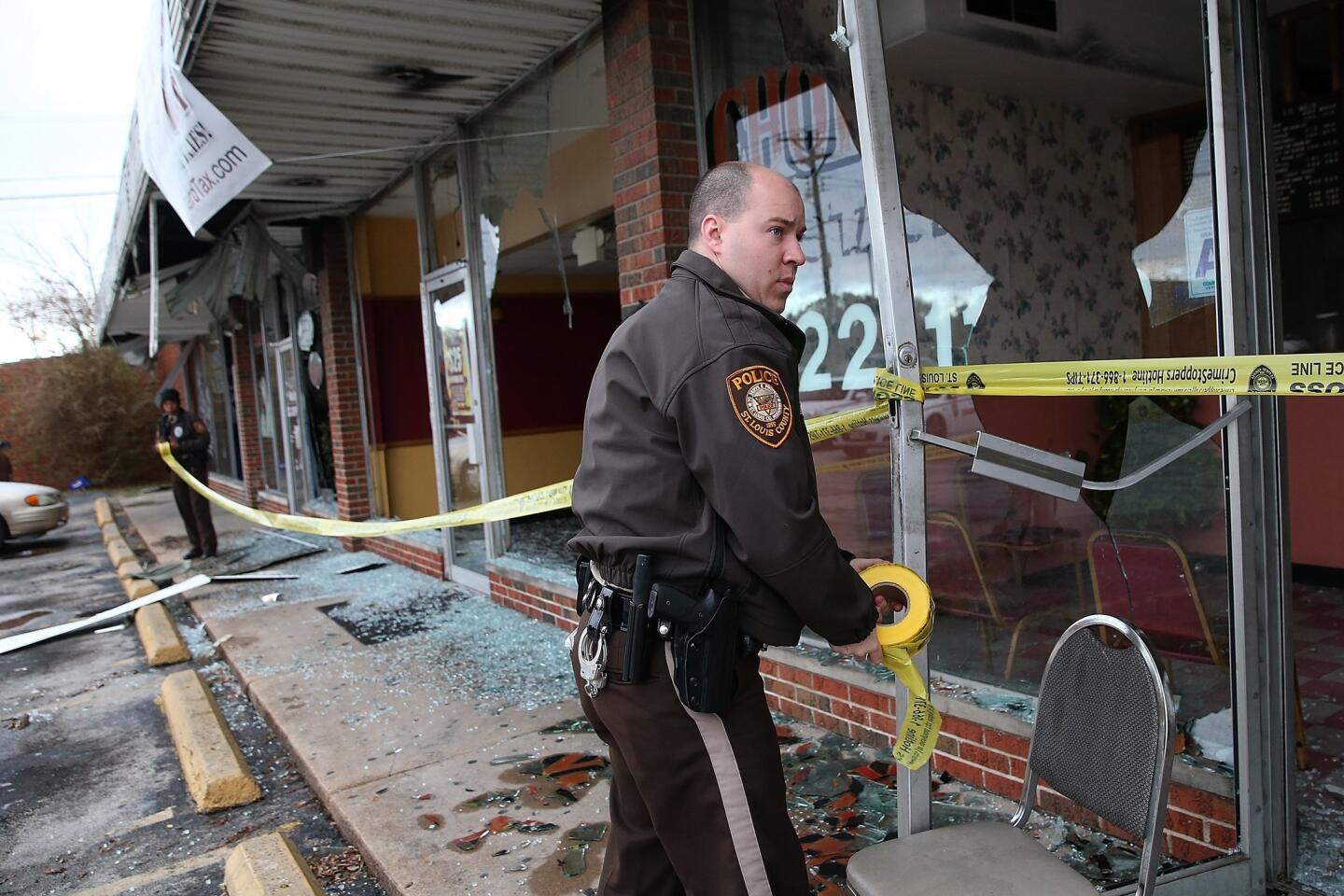

St. Louis County Police Chief Jon Belmar told reporters early Tuesday that the night’s unrest exceeded anything that happened in August, in the days after Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson shot Brown.

Police in riot gear faced off Monday night against protesters along West Florissant Avenue in Ferguson, the commercial strip that has become the gathering spot for demonstrators since Brown’s death. At least a dozen buildings were burned, Belmar said, and he personally heard 150 gunshots.

Crowds also gathered outside the Ferguson Police Department. Tear gas was fired. Gunshots were heard, but in the chaos it was impossible to know who fired them.

“Our lives don’t matter! Our lives don’t matter!” one protester shouted as he ran through a crowd outside the police headquarters, where hundreds had gathered in anticipation of the announcement.

Officers took cover behind police cars as protesters hurled bottles, rocks and at least one megaphone at them. Officers fell to their knees and held their shields over their heads for protection.

“Don’t throw it!” one officer shouted at the crowd.

Police fired back with tear gas and bean bag rounds, but that did not deter the crowd.

By 9:30 p.m., a police car had been set afire and was burning out of control, about a block from police headquarters. Soon, a second police car was ablaze.

Belmar said 29 people had been arrested so far, but no serious injuries to police or protesters had been reported. “The good news is that we have not fired a shot,” he said.

Highway Patrol Capt. Ron Johnson lauded authorities’ restraint. “The officers did a great job tonight,” he told reporters. “They showed great character.”

Belmar and Johnson said they were disappointed at the violence.

“I didn’t see a lot of peaceful protests out there tonight,” Belmar said.

In University City, another St. Louis suburb, a police officer was shot in the arm, but Belmar said that appeared to be “totally unrelated to events here in Ferguson.”

Before the mayhem began Monday, Brown’s family issued a statement asking for peace. “We are profoundly disappointed that the killer of our child will not face the consequence of his actions,” the family said.

“While we understand that many others share our pain, we ask that you channel your frustration in ways that will make positive change,” the family statement continued.

President Obama also appealed for calm and said protesters should honor the Brown family’s wishes.

“We have made enormous progress” on racial issues, the president said. “To deny that progress is, I think, to deny America’s capacity for change. But what is also true is that there are still problems, and communities of color aren’t just making these problems up.”

McCulloch said that after hearing more than 70 hours of testimony from 60 witnesses, and examining evidence that included three separate autopsy reports, jurors were faced with a web of contradictory statements that made it impossible for them to conclude that Wilson should face criminal charges.

“The duty of the grand jury is to separate fact from fiction,” McCulloch said, adding that the jurors, who are anonymous, deliberated for two days.

He did not say what their vote was. A grand jury needs nine of the 12 members to vote to indict.

McCulloch said the grand jury matched witness testimony against physical evidence, which showed that Brown sustained no gunshot wounds to the rear of his body, but rather to his thumb, right arm, chest, forehead and the top of his head.

The first two shots were fired inside Wilson’s sport utility vehicle, with one apparently grazing Brown’s thumb, the prosecutor said, an account consistent with police claims that the confrontation began when Brown — ordered out of the middle of the street when Wilson sought to ask him about a convenience store theft — reached through the window of the police car and started a scuffle.

The officer then gave chase on foot, McCulloch said, with the fatal shots fired as Brown turned back to confront the officer.

“Physical evidence does not look away as events unfold,” he said.

Even after the prosecutor’s calm recitation of the evidence, anger and heartbreak ruled the night in Ferguson.

Though most black residents had been skeptical that the grand jury would indict Wilson, many had hoped that he would face charges. The jurors could have indicted him on charges ranging from involuntary manslaughter to murder.

“I’m really hurt. There is no justice in America for the black male species,” said Christine Ewings, 46, a cousin of Michael Brown. Ewings was with Brown’s grandmother in Ferguson as the jury’s decision was announced.

But state Rep. Jeff Roorda, business manager for the St. Louis Police Officers’ Assn., said the decision matched his belief all along: that Wilson’s shooting of Brown was justified.

“The rush to judgment that started Aug. 9 should have stopped a long time ago,” he said.

Lawyers for Wilson, who has remained out of sight since the shooting but who testified before the grand jury, expressed relief.

“Law enforcement personnel must frequently make split-second and difficult decisions. Officer Wilson followed his training and followed the law,” their statement said.

The decision was months in the making, and the length of time the grand jury met served only to heighten the tensions that have roiled the St. Louis area since Brown’s death. The jurors began hearing testimony and reviewing evidence on Aug. 20.

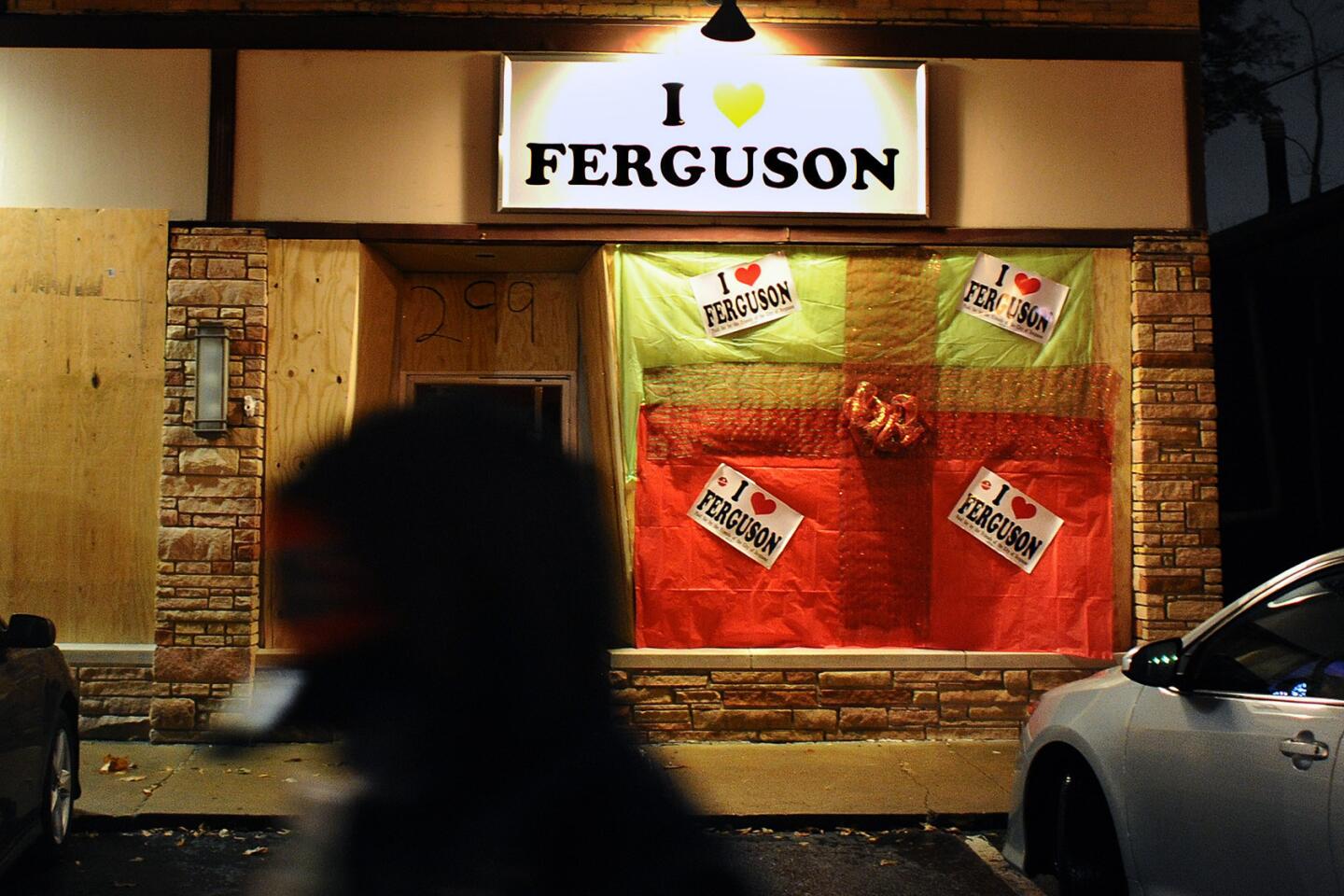

St. Louis County began preparing as if a major storm were bearing down. Windows of storefronts vanished behind wooden planks. Schools closed early. Barricades went up around the County Justice Center in Clayton, where the jurors met and where a protest swelled Monday evening in anticipation of the announcement.

Mailboxes were locked and statues and monuments were wrapped to prevent vandalism, but that failed to prevent arsons and looting.

The most compelling calls for peace came from Brown’s parents, who since their son’s death have been thrust onto the world stage as the tragic symbols of what is wrong with policing in America.

“I thank you for lifting your voices to end racial profiling and police intimidation. But hurting others or destroying property is not the answer,” Michael Brown Sr. said in a video uploaded last week by St. Louis Forward, a civic group.

Brown said that no matter what the jury decided, he did not want his son’s death to be in vain.

“I want it to lead to incredible change, positive change, change that makes the St. Louis region better for everyone,” Brown said.

Brown’s family asked for 4 1/2 minutes of silence in honor of their son after the grand jury announcement, to mark the 4 1/2 hours that the younger Brown’s body lay in the street.

Not everyone folded in fear of violence.

Business was booming at the Ferguson Burger Bar & More, a popular eatery off West Florissant, where the wide-screen TV was on Monday evening while customers chowed down on cheesesteaks and fries.

“I have faith in my community,” said the owner, Charles Davis, who refused to close his doors early or board up his windows.

Others, black and white, gathered in churches and community centers to prepare for the worst, and to pray and hope for the best. But as they awaited the outcome, their often disparate views of the situation laid bare the gaps that need to be closed.

Linda Lipka, 50, a longtime Ferguson resident who is white, hoped to provide a voice that could bridge racial tensions. She said she empathized with protesters but added, “They’re saying these horrible things to the police officers who are protecting their right to do it.”

She fretted over the number of people she knows who have bought guns, and over the impact on local businesses, which need holiday season shoppers to survive. And she worried about the way people in town have lost faith in one another.

“I don’t like that concern everybody has in their mind now — do you still like me? Am I still your friend?” Lipka said. “There’s some of us that refuse to let that change us. I look everyone in the eye and say hi. And I always did.”

Outside the Canfield Green apartment complex where Brown lived, Romana Williams, 63, who is black, had a very different set of concerns.

“These young people are tired of seeing people just getting killed, not just by our own people but by police,” said Williams, who never expected Wilson to be charged. “It will never change.”

“And it is a black and white issue,” Williams added. “And it’s never going to change. People say yes it will, yes it will — when is it going to change?”

molly.hennessy-fiske @latimes.com

Glionna and Pearce reported from Ferguson, Hennessy-Fiske from Houston and Susman from New York. Staff writers James Queally in Ferguson and Cathleen Decker and Lauren Raab in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.