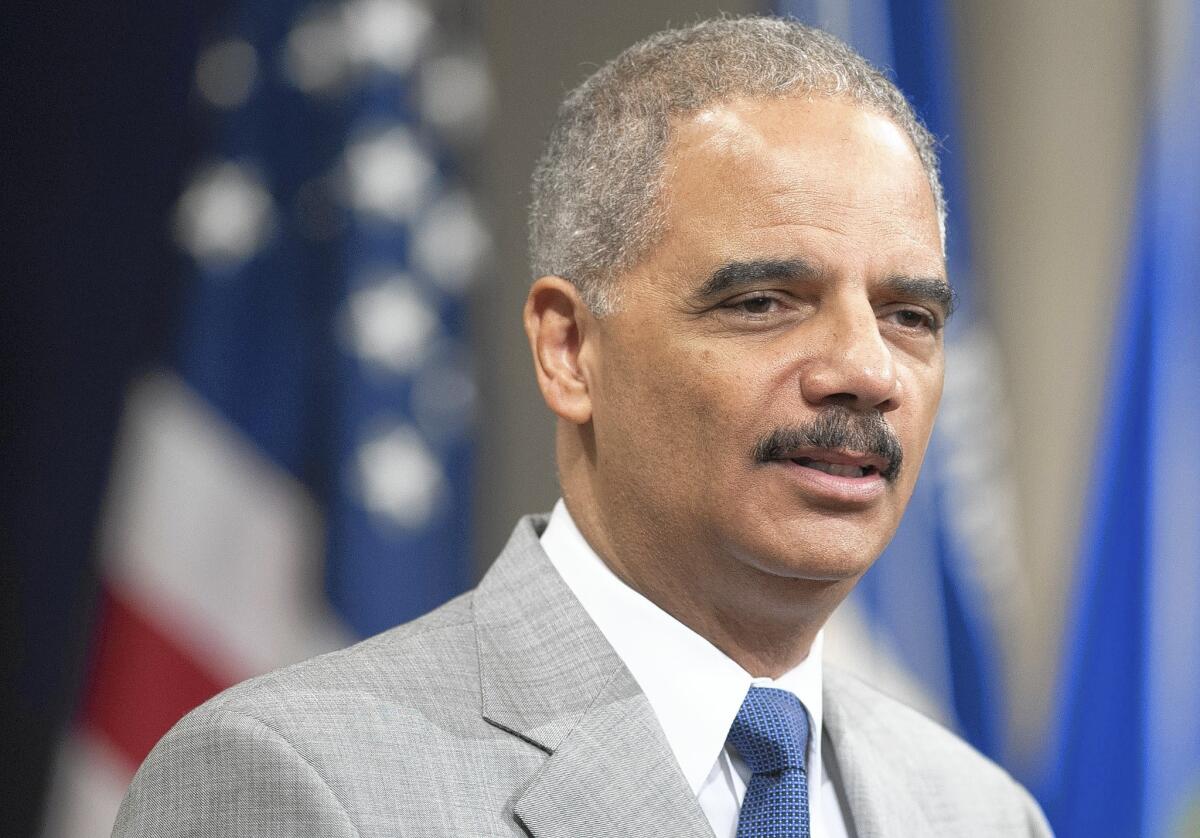

Eric Holder’s trip to Ferguson, Mo., rooted in his civil rights pledge

Reporting from WASHINGTON — Eric H. Holder Jr.’s planned trip Wednesday to the center of riot-torn Ferguson, Mo., in many ways began 5 1/2 years ago, when he became the nation’s first African American attorney general and pledged to make federal civil rights enforcement a hallmark of his administration.

The police slaying of Michael Brown has presented Holder with what could be the biggest challenge yet to his legacy as the nation’s top civil rights advocate, prompting what many are calling an unprecedented federal investigation into the shooting death of the unarmed black 18-year-old.

In stark contrast to the Justice Department’s usual handling of such cases — in which local government agencies take the lead — Holder appears locked in an odd and unsteady competition with Missouri officials over which of them, if either, will prosecute Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson first.

Justice Department officials say the unusually aggressive federal intervention is justified by the continuing violence and apparent mishandling of the case by local officials, who have been criticized for displaying excessive force against protesters and moving too slowly to investigate the Aug. 9 shooting.

But law enforcement officials and other experts could not recall another instance in which Washington pushed ahead with a federal civil rights case as it has in Ferguson, almost elbowing state officials out of the way.

In the days since Brown was shot on a Ferguson street, the attorney general has repeatedly briefed President Obama, dispatched dozens of FBI agents to interview witnesses and ordered a now-completed federal autopsy, despite two earlier autopsies done at the request of the state and Brown’s family.

Holder has sharply and publicly signaled his mounting frustration with state and local officials, whom he blamed for stoking public unrest by at first refusing to identify the officer and then releasing — against his advice — a video of Brown purportedly robbing a market before the shooting.

In the wake of nationally televised images of armored vehicles and military-style weapons being deployed on the streets, Holder publicly warned local law enforcement agencies against “unnecessarily extreme displays of force.”

Holder’s visit Wednesday is the latest example that he is taking a strong personal interest in the Ferguson investigation, in contrast to Obama, who has kept a lower profile in the racially charged case.

In an op-ed piece published Tuesday by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Holder characterized the unrest in the community as a “demand for answers about the circumstances of this young man’s death and a broader concern about the state of our criminal justice system.”

Many praise the federal stance, saying a credible criminal investigation will ultimately ease rage in Ferguson, a predominantly black community where many protesters fear the local prosecutors are determined to exonerate the officer, who is white.

In a sign that Holder’s campaign is gaining traction in the area, a group of African American lawyers held a news conference Tuesday in front of the St. Louis County courthouse, calling on local prosecutor Robert McCulloch to recuse himself. They said the federal investigation should proceed first because McCulloch appears to be “emotionally invested in protecting law enforcement.”

Yet with all of Holder’s determination, the reality is that state prosecutions almost always go first and that a federal civil rights case could be harder to build and win than a state case involving a charge of murder or manslaughter.

Matthew Miller, a former Justice Department chief spokesman, said Holder’s approach underscored his resolve to make civil rights a benchmark of his tenure as the nation’s attorney general.

“You have to understand where this case comes from and what it means to civil rights under Holder,” Miller said. “Go back to the beginning of his tenure, to his confirmation hearings. He made one of his key promises that he would restore the credibility of the department’s civil rights division. And he is doing that.”

Department officials acknowledge that there is a tremendous amount riding on Holder’s handling of the investigation, and that the more he gets out front publicly, the more he will be expected to deliver criminal charges.

Holder is betting that federal action will quiet the nightly violence, according to one Justice Department official, who spoke anonymously because of the delicacy of the situation in Ferguson and at the department.

“He believes maybe showing the flag will help quell the tension,” the official said. “The attorney general has always been about race, and it happens here that the victim is black and the police officer is white. Yet one wonders how much that is playing a part in his extraordinary decision to go ahead with this.”

Another official, also speaking anonymously, said the situation could reach a tipping point where federal criminal charges would be the only way to vindicate Holder’s public comments and show that the federal government is serious.

“He sees a duty to prosecute or look into potential civil rights violations,” the official said. “There’s nothing wrong with that. But once you’re all in, you’re all in.”

Since taking office in 2009, Holder has focused on several changes to correct what he sees as racial imbalances in the American justice system, such as mandatory prison sentences that weigh more heavily on black drug offenders.

He also has ramped up federal oversight of local law enforcement, bringing 33 legal actions against police departments for policies or practices of abuse, including in Los Angeles and Baltimore. So far 16 cases have yielded court decisions or settlements that resulted in reforms.

But with Ferguson, some question whether Holder is going too far, inserting himself into a matter best handled by local authorities.

“While the federal government can assist with that investigation, the federal government should not assume the state and local governments’ responsibilities,” Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) said this week.

It’s not uncommon for both state and federal agencies to get involved in high-profile cases. In the 1991 beating of Rodney King, the state prosecuted four Los Angeles police officers. After they were acquitted, sparking the Los Angeles riots, the federal government prosecuted the officers on civil rights violations, resulting in the conviction of two.

Sometimes the reverse happens.

In the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, the federal government took the lead in the terrorism case. Timothy McVeigh was convicted and later executed. His accomplice, Terry Nichols, was given a life sentence without parole. That prompted Oklahoma officials to try him on state charges, hoping for a death sentence. Instead, he was again sentenced to life imprisonment.

A long-standing government policy calls for federal prosecutors not to charge individuals with the same crimes leveled by state authorities. But they can bring charges if the federal government determines it has separate “interests,” such as a violation of someone’s civil rights. In practice, federal agencies usually get involved only after local authorities have proved unwilling or unable to secure convictions in high-profile cases.

It remains unclear whether Holder is actually considering putting the federal prosecution first or just trying to keep pressure on local authorities to ensure they conduct a vigorous investigation.

If it’s the latter, the tactic may be working. On Tuesday, county officials said they expected to begin presenting evidence to a local grand jury Wednesday.

@RickSerranoLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.