Forget Carnegie Hall. Musicians rush to rural Colorado to play the Tank

Reporting from RANGELY, Colo. — People here speak of the old water tank on the edge of town in almost mystical terms, like it’s a living, breathing thing rather than a 65-foot-high tower of rusty steel.

They call it the Tank, with a capital T, and it stands on a hill overlooking a gravelly desert.

Every Saturday, visitors from as far away as Germany drive out to the graffiti-scarred cylinder for a turn inside with their guitars, flutes, harps, kazoos or just their own voices.

“No two times are the same,” said Samantha Wade, 26. “The key is listening. When you listen you can see what notes the Tank is taking hold of. It’s a totally new experience for most traditional musicians.”

She walked inside. The 40-foot-wide Tank was warm and dark. A shaft of sunlight streamed through a porthole, bathing her in gold.

Wade vocalized a range of sounds, her voice rising steadily. Each note echoed for up to 40 seconds, staying just ahead of the one behind and turning her singular voice into an ethereal choir.

“When I sing, the Tank and I work together,” she said. “I become one with the Tank.”

With a population of about 2,200, Rangely sits on the northwest edge of Colorado, some five hours from Denver. It’s a culturally and politically conservative town of oil and gas workers, an unlikely destination for hippies and musicians.

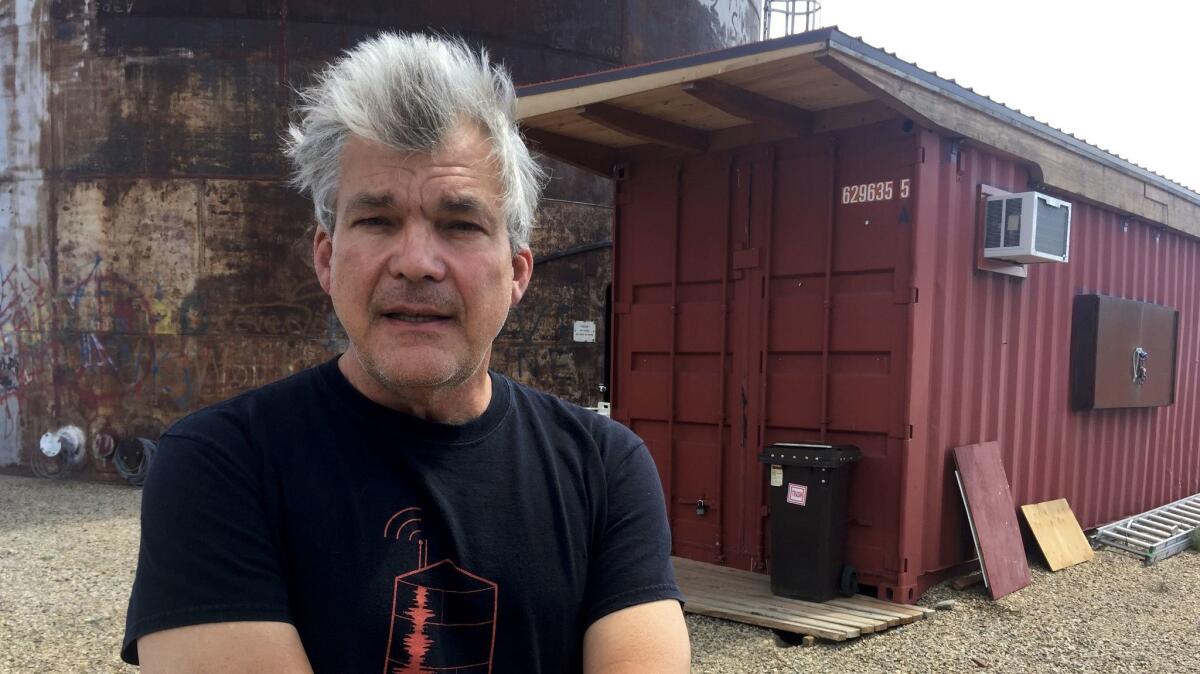

Bruce Odland, 65, is something of both. The New York composer and sonic explorer discovered the acoustic eccentricities of the Tank while traveling through town in 1976 as part of a state-sponsored arts festival.

He was wandering around Rangely looking to record local sounds when two men pulled alongside him in a pickup.

“These roughnecks told me to get in,” Odland recalled. “They drove me up to the Tank. They got me inside and began throwing rocks against the side. I had never heard sounds like that.”

A few hours later, Odland and his fellow musicians returned with Japanese instruments, the only ones they owned that were skinny enough to follow them through the 18-inch porthole.

As they played, the Tank awakened.

It bent and elongated each note with its concave roof, smooth walls and warped floor. And with no means of escape, the reverberations went on and on and on. It was, as Odland said, a “living sound-shaping entity.”

For the next two decades, he and other musicians returned to record albums with names like “The Soaring Bird” and “Leaving Eden” inside the Tank.

“It had a cathedral ‘wow’ factor times 10, minus the crucifixes,” he said.

The Tank’s origins are murky, but local writer Heather Zadra said it was once owned by the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad and probably serviced steam locomotives near the Colorado towns of Rifle and Parachute. In the early 1960s, a power company bought it and moved it to Rangley for use in fire suppression. But officials feared that filling it would collapse the hill. So it sat empty.

Yet it was quietly morphing into something extraordinary.

“The Tank was set on pea gravel. All the weight was on edges, which bent the bottom of the floor upward,” Odland said. “Instead of sound simply going up and down, it bounced around inside the Tank. There is nothing to absorb it but human bodies.”

For locals, it was a place to party. There were fevered rumors of seances, devil worship and other lurid goings-on inside.

Wade found something else when she went in about age 10. Her grandmother lived at the bottom of the hill and knew Odland and his friends well.

“There were candles and people playing guitars. It was the most magical place I ever saw,” Wade said. “My grandma kept the key for them. Sometimes they would run electrical cords from her house to the Tank. As she got older I kept the key. I started singing inside. I became a Tank singer.”

The Tank had many owners over the years including a friend of Odland’s who bought it for $10. But the liability insurance became too much and there was talk of selling it for scrap. That’s when Odland and a group called Friends of the Tank moved to save it.

First they needed the town’s help to guide them through the permitting process and other bureaucracy.

So in 2013, Lois LaFond, a singer-songwriter from liberal Boulder who performed with Odland, came before the town council to make the case.

“They knew I was from Boulder, so there was this immediate wall of ice,” she said.

Her husband, Richard, a civil rights attorney, raised some hackles by not reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, believing the part about “one nation under God” violated the separation of church and state.

Sensing disaster, LaFond invited the council members to experience the Tank themselves. The next morning those who could fit through the porthole crawled inside. Councilwoman Elaine Urie hummed and then sang “Amazing Grace.” LaFond sang with her.

“I fell in love with the Tank,” Urie recalled.

It was a turning point. The town embraced the Tank.

And perhaps that’s the real story: a collection of artists and avant-garde musicians from all over the world making common cause with a conservative town in rural Colorado.

“Normally we wouldn’t have the compatibility to even get a cup of coffee together, and now we’ve created this exceptional relationship,” LaFond said. “I think hearts and minds on both sides were opened.”

Urie and her husband, who own a trucking and gravel company, built a road to the Tank and made a parking lot. Someone else cut a human-size door into the side.

Kickstarter campaigns in 2013 and 2016 raised more than $100,000, enabling Friends of the Tank to buy the silo and the land around it, erect fencing, install lighting and put a recording studio into a donated railroad car.

The Tank Center for Sonic Arts was born and is now a growing performance venue. The Flobots, a hip-hop group from Denver, and the Grammy Award-winning Roomful of Teeth have played inside.

It now has three employees, including Wade, an assistant sound engineer who coordinates recording sessions.

There is hope that it can boost an economy hit hard by a slump in oil and gas prices.

“Any hotel stay or retail sale it generates is welcome,” said the town manager, Peter Brixius. “It’s becoming a niche venue for certain people. It’s a really good road-trip destination.”

Customers at Giovanni’s Italian Grill can order the Tank pizza. The Blue Mountain Inn & Suites bills itself as the “Exclusive Lodging Partner of The Tank.”

The town’s website calls the Tank a “sonic wonder of the world with a shifting, swirling reverberation longer and richer than the Taj Mahal and the Great Pyramid.”

On Saturdays, it is open from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. for visitors to make music or just listen. Recording sessions can also be arranged.

Newcomers quickly learn to take it slow, lest the notes run together. Sounds can echo nearly a minute. With practice, one person can sing a duet.

Lisa Hatch, a town council member and an Army veteran, said the Tank was part of her therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It all dissipated the first time I played my violin in the Tank,” she said. “I was in the moment. Sound surrounded me. The Tank really plays us.”

She went inside and played “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.”

Eva Restad, 31, of Oakland was next, running a violin bow across a bent saw that sounded like high-pitched singing whales.

A black lab stuck his head inside, barked once and listened to a pack of dogs bark back.

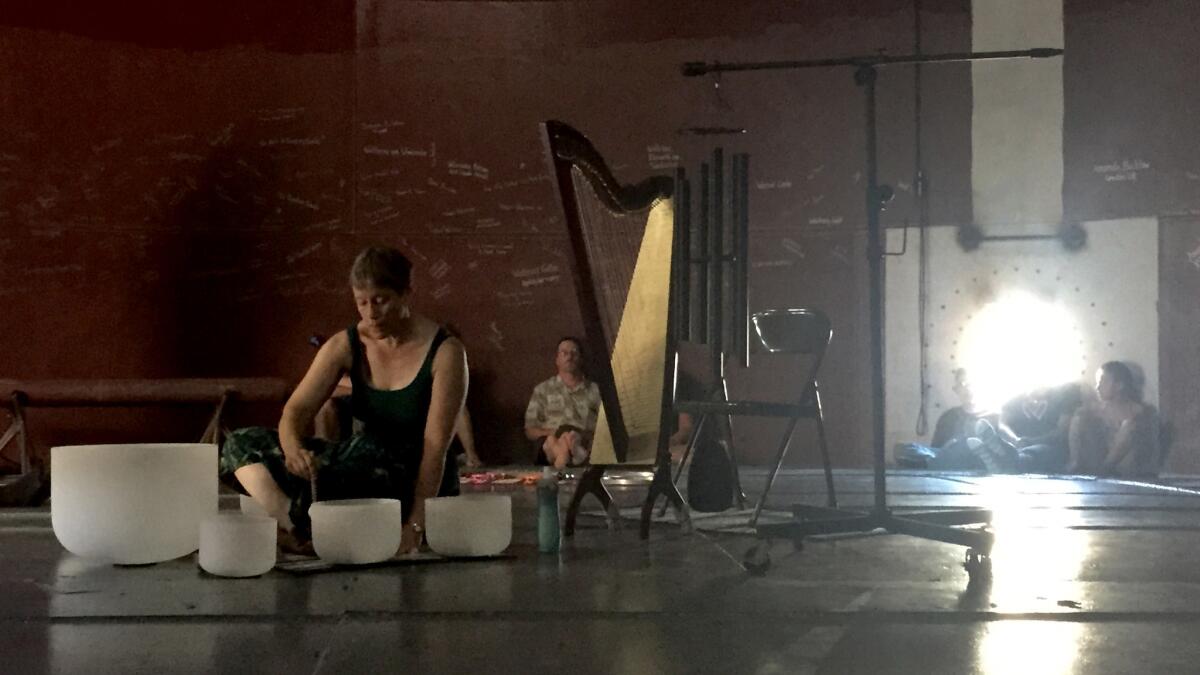

At noon, Christina Hildebrandt from Longmont, Colo., gave a performance before a capacity crowd of 49, coaxing haunting sounds from a selection of crystal “singing” bowls.

“Human beings are vibratory creatures,” she said. “We respond to the world in a vibratory way.”

Odland drifted in near closing time. He had just bought a house in Rangely to be near his beloved metallic cathedral.

He wants to build an amphitheater next door, piping in music from the Tank.

“The sound echoes up the hills into the sky, and it sounds fantastic,” he said.

Then he locked the gate and drove off.

For the first time that day, the Tank stood silent.

Kelly is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.