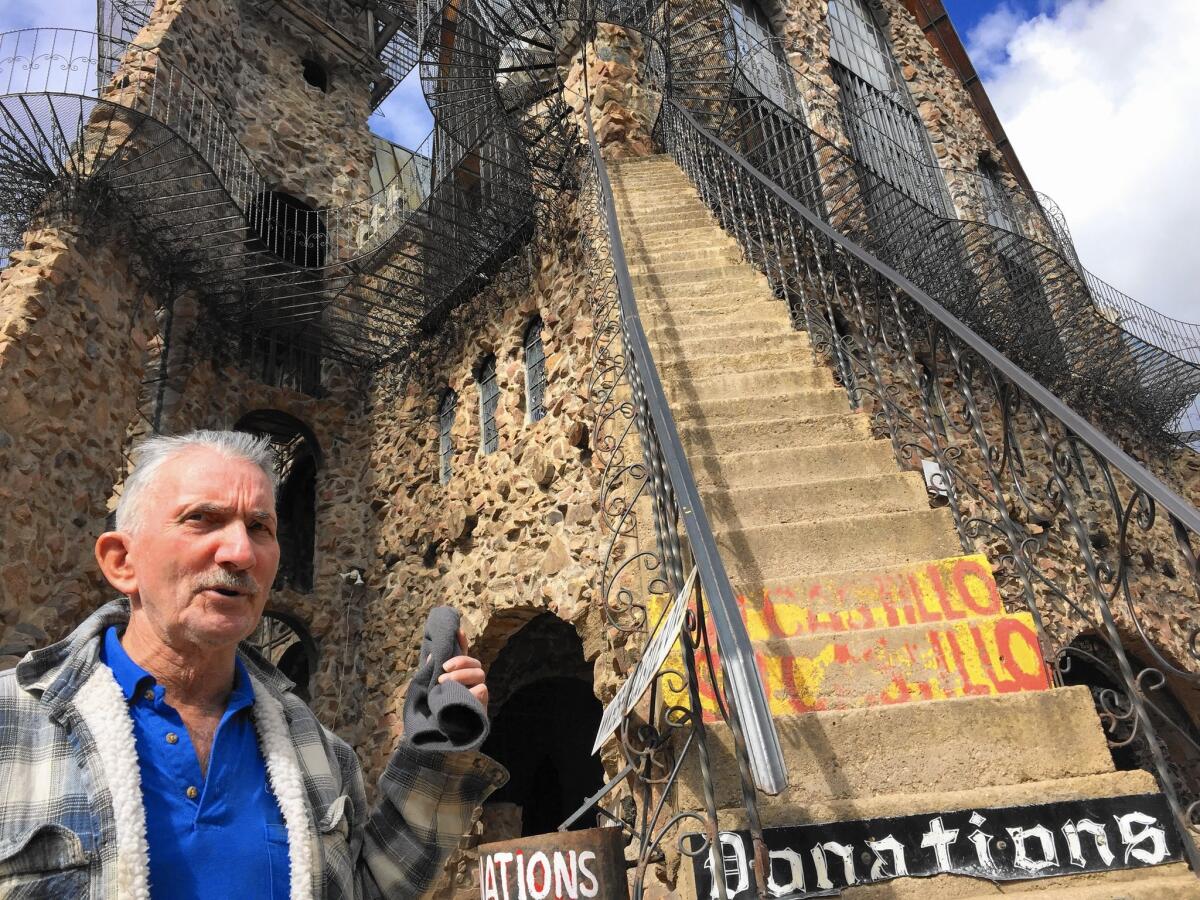

Colorado castle is one man’s hand-built monument to freedom

Reporting from RYE, Colo. — It’s best not to ask Jim Bishop when he might finish his fairy-tale castle. It only riles him up.

“When I don’t wake up one morning, then it will be done,” he declared, rising from a chair beside his mighty 160-foot-high fortress of rock and stained glass. “And I don’t need no help from nobody!”

His wife, Phoebe, gave him a look.

“Jimmy, sit down,” she said as he slowly retook his seat.

It’s been a tough year for Bishop. He suffered a nervous breakdown and was diagnosed with Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare cancer. On top of that, he says someone tried to swindle him out of his beloved citadel, which sits at 9,000 feet in the San Isabel National Forest.

“No one will ever control this castle but me,” he said.

For the last 47 years, stone by agonizing stone, Bishop has pursued a dream of building his own mountain redoubt with little more than old National Geographic magazines for architectural guidance. Working alone with makeshift pulleys and his own weather-beaten hands, he slowly transformed a small cottage into something truly monumental.

With its flying buttresses, great hall, hair-raising spiral staircases and a silver dragon’s head that spews fire, Bishop Castle, about 145 miles south of Denver, has attracted worldwide fame.

Yet even Bishop, 71, has a tough time explaining what it all means.

“It’s about freedom,” he said, after thinking a while. “People realize they can do anything.”

Bishop Castle sits near the town of Rye about 145 miles south of Denver. It was built by Jim Bishop.

It’s also an enormous Gothic soap box to spout his strident anti-government views to tens of thousands of visitors each year. Signs everywhere point to the perfidy of federal authority. “There ain’t a dime’s worth of difference between a Democrat, Republican and Marxist,” says one.

The Internal Revenue Service, the United Nations and law enforcement are frequent targets for tirades. His battles with the Forest Service over road access and parking helped fuel some of this hostility. And if visitors flinch, he’s quick to tell them that admission is free and so is leaving.

Yet Bishop’s health problems along with legal bills incurred in his fight to regain the castle have taken a toll.

Last February, at a time when Bishop says he was “not sound of mind,” then-friend David Merrill asked him to sign an agreement making him a trustee of the castle. Merrill immediately claimed he owned the place and renamed it “Castle Church for the Redemption of the Office Bishop.”

SIGN UP for the free Great Reads newsletter >>

Merrill, who could not be reached for comment, has a long history of litigation. After his motor scooter was seized for expired plates, he sued the UN, the Colorado Springs police chief, the ancient Jewish high court known as the Sanhedrin and Jesus Christ.

According to a 2001 story in the Rocky Mountain News, the Denver District Court judge called the suit a “rambling, nonsensical, incoherent blotch on this court’s docket” and dismissed it.

The Bishops sued Merrill, claiming he tricked them into signing phony documents making him a trustee of the castle. Merrill didn’t file a response, so on Sept. 25 an El Paso County District Court judge ruled in favor of the Bishops, nullifying the agreement, deposing Merrill as trustee and effectively banning him from the property. She also awarded the couple the estimated $20,000 in legal costs.

But they still have to pay the costs upfront until they are reimbursed, which could take months. So fundraisers are being held and visitors are being asked to donate.

Fundraisers are being held and visitors are being asked to donate to help defray Jim and Phoebe Bishop’s medical and legal expenses.

On a recent autumn day, people from as far away as Australia gingerly navigated the winding staircases or walked between castle turrets.

“No one ever falls because they sense the danger and hold on tighter,” said Bishop, sitting with his wife at a small table with a donation can.

A grizzled man in a tattered jacket dropped in $20.

“I appreciate the rock work,” he muttered.

Autograph seekers all got the same signature: “Jim Bishop — the Castle Builder.”

The nervous breakdown has left Bishop a bit fragile around people. He is easily agitated and usually requires an afternoon nap beside his albino Chihuahua, Punkin.

“Right now his body is his castle,” his wife said. “That’s our priority.”

Bishop is trying to beat his cancer with an alkaline diet.

“Cancer cannot survive in a high-alkaline environment,” he says repeatedly.

He swigged a concoction of lemon juice, spring water and stevia. Then he drank the olive oil inside a can of sardines. He finished with Fig Newtons and peanut butter eaten from the jar with a spoon.

“The doctors are starting the use the words ‘benign’ and ‘miraculous’ when I see them now,” he said.

Anita Bunnell, 56, of Indianapolis approached the table.

“I literally have tears in my eyes,” she said. “I guess it’s the emotion I feel when I see what humans can do.”

Phoebe, 67, smiled.

“I told Jim, ‘If you can make a three-tiered cake stand, you can build a castle,’” she said.

Bishop, whose family owned an ornamental iron shop in Pueblo, began building here in 1969. His goal was a small stone cabin in the woods.

“But people kept asking if I was building a castle, so I thought, if people want a castle I’ll give them a castle,” he said.

With his life’s mission abruptly laid before him, he toiled on the castle whenever he had free time, even in the freezing winters when night fell early and he cursed the darkness for stalling his quest.

Ironically, the couple never moved in. They have a small apartment over the gift shop but their home is not their castle. Their home is in Pueblo and their castle pretty much belongs to everyone else. As long as visitors don’t drink or vandalize and leave by nightfall, the Bishops don’t seem to mind.

A man from Oklahoma wandered up to the couple and asked if they would sing “Happy Birthday” to his wife back home.

They happily obliged. Then Jim looked into the camera.

“Remember this,” he announced. “Cancer cannot survive in a high-alkaline environment.”

Kelly is a special correspondent.

ALSO

How the U.S. plans to stop the next Edward Snowden

Heartbroken man spends more than $700,000 on psychics, chasing after lover

U.S. government proposes 17-year delay in start of Hanford nuclear cleanup -- until 2039

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.