A Medal of Honor, long delayed

John ‘Mac’ MacFarland, who wrote the recommendation, knew fellow soldier Santiago Jesse Erevia’s bravery in Vietnam deserved the highest honor. But something stood in the way.

Using an ammo crate as a chair and an Army tent as his office, Pfc. John "Mac" MacFarland set up his typewriter and began to write.

It was the sweltering summer of 1969, about a month after the fierce battle of Tam Ky in South Vietnam. MacFarland had been ordered to write a recommendation nominating Spc. 4 Santiago Jesse Erevia for the Medal of Honor, and he tried to put into words how Erevia's "conspicuous gallantry" had saved so many fellow soldiers.

"Although Erevia could have taken cover with the rest of the group," MacFarland wrote, "he realized that action must be taken immediately if they were able to be relieved from the precarious situation they were now in."

MacFarland, a 23-year-old college student who had been drafted, spent weeks working on the nomination, sure that Erevia, a 23-year-old high school dropout who had enlisted, would be awarded the medal. MacFarland sent the recommendation up the chain of command.

"And then I never heard another thing," MacFarland recalled decades later.

Erevia knew that he had been nominated, and though admitting initial disappointment that he did not receive the Medal of Honor, he went home to Texas and never dwelt on it.

MacFarland did.

Over the decades, he searched lists of Medal of Honor recipients, looking for Erevia's name. Again and again, he dug out his mimeographed copy of the recommendation, fearing he had failed to capture Erevia's extraordinary heroism.

"I found myself … wondering how I could have done a better job," MacFarland said.

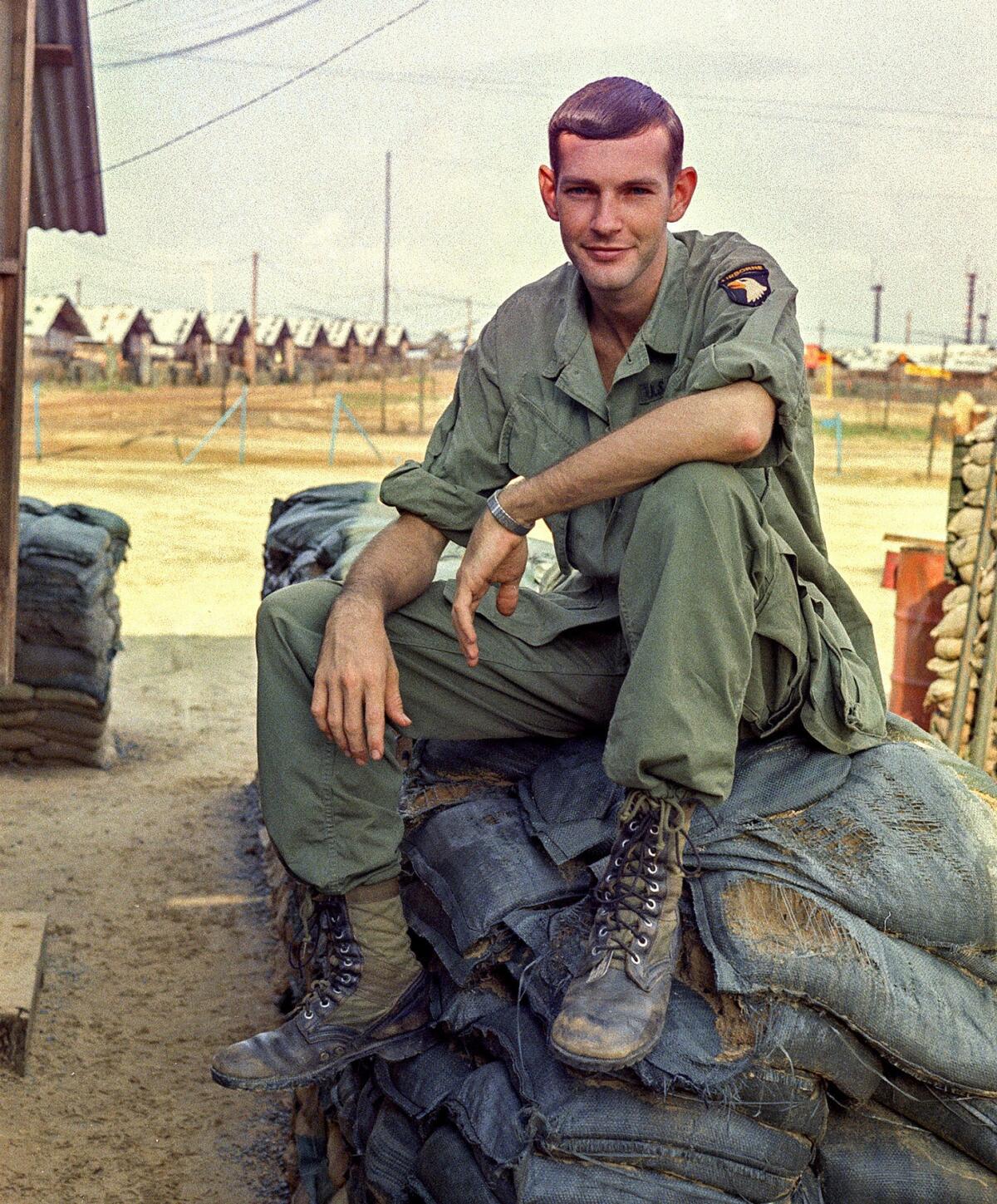

Army PFC Pfc. John "Mac" MacFarland in 1969. Shortly after the battle of Tam Ky in South Vietnam that year, MacFarland was assigned to write the Medal of Honor recommendation for Spc. 4 Santiago Jesse Erevia, whose "conspicuous gallantry" had saved many soldiers. (Don Kelsen / Los Angeles Times) More photos

He thought of writing Erevia to say he was sorry the recommendation fell short. But he never wrote.

"This became one of the ghosts that haunted me," MacFarland said.

It wasn't until this year, 45 years after the battle, that MacFarland would learn the disturbing truth — the real reason Erevia had been denied the nation's highest military honor.

They arrived at Company C with different backgrounds and under different circumstances.

Erevia was born in Nordheim, Texas, and had dropped out in 10th grade. He enlisted in the Army at 22 after working as a cook and soda deliveryman.

"I thought maybe I could better myself," he said.

MacFarland was a college engineering student in Pennsylvania. He was drafted and was prepared to serve. "As an Eagle Scout, my duty to my country was clear to me and had been since I became a Boy Scout at the age of 11," he said.

Erevia doesn't remember MacFarland. But they were together on May 21, 1969, in the fight for Tam Ky, south of Da Nang.

Company C had taken shelter behind a stone wall, under fire from North Vietnamese troops dug in on a hill at the other end of a dry rice paddy. The North Vietnamese were holed up in heavily camouflaged spider holes and bunkers.

This became one of the ghosts that haunted me.”— John “Mac” MacFarland

As MacFarland noted in the recommendation, about 4 p.m. their unit was ordered to "move out and engage the enemy." The aim, he recalled, was to take pressure off other companies so they could evacuate their dead and wounded.

MacFarland joined other soldiers in going over the wall, firing his rifle as he stepped into the rice paddy. When another soldier fell wounded, MacFarland rushed to his aid.

Erevia came over to MacFarland and the wounded soldier and asked whether they had any extra ammunition. The wounded man handed Erevia his M-16 rifle, magazines of ammunition and several hand grenades.

"It was the last that I saw Jesse until much later that evening," MacFarland said.

Erevia, who was serving as the radio-telephone operator, made it across the rice paddy, which was as long as a football field. As Erevia and other soldiers remained under heavy fire, he and a friend, Spc. Patrick Diehl, took cover behind a tree.

Erevia chokes up talking about that day. "I asked Diehl, 'Do you see anything?' He never answered."

Diehl had been fatally shot in the head.

At a military store in San Antonio, Erevia's wife, Letici, helps him pick out a uniform for his Medal of Honor ceremony at the White House on March 18. (Joe Raedle / Getty Images) More photos

Erevia decided he needed to act. "It was either do or die," he recalled in a recent interview. "I said, 'Well, if I'm going to die, I might as well die fighting.'"

Erevia ran toward one of the bunkers and threw in a grenade, killing the soldier inside. He moved to a second bunker, bullets still flying around him, and tossed another grenade to knock it out too.

As MacFarland would later write about Erevia: "After reloading his rifles, he advanced toward the third bunker behind the suppressive fire emitted from his weapons." Once again, he took out the bunker with grenades.

After exhausting his supply of grenades, Erevia headed for a fourth bunker while firing two rifles. He killed a North Vietnamese soldier at point-blank range.

"Our company commander, Capt. David Gibson, along with his radio-telephone operators and medic and several wounded had been pinned down and were receiving intense fire from several enemy positions," MacFarland recalled. Without Erevia, "it is doubtful that they would have survived the day."

Shortly after the battle, MacFarland was assigned to serve as battalion awards clerk. Using information provided by others, he wrote the Medal of Honor recommendation, got it signed by the battalion's commanding officer and forwarded it to 101st Airborne Division headquarters.

After it was sent back for more information, Erevia's company commander and platoon leader provided eyewitness accounts and a map of the battle. MacFarland ran off several copies on a mimeograph machine, keeping one for himself.

The next year, 1970, Erevia and MacFarland left Vietnam and went their separate ways.

I said, ‘Well, if I’m going to die, I might as well die fighting.’”— Santiago Jesse Erevia

Erevia became a mail carrier, retiring in 2002 after working 32 years for the Postal Service. He lives in San Antonio with his wife, Leticia. He has four adult children, including a son who served in the Iraq war.

MacFarland went on to become a high school environmental science and biology teacher. Also retired, he is a bachelor living in Aston, a Philadelphia suburb. The two men, now 68, have had no contact since leaving Vietnam.

Though denied the Medal of Honor, Erevia was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the decoration created during World War I and the nation's second-highest military honor for heroism. The citation quoted language written by MacFarland.

MacFarland kept his copy of Erevia's recommendation in a binder with photos and other Vietnam memorabilia. He shared his distress about Erevia and the Medal of Honor with Army buddies. They assured him that it wasn't his fault and that the military probably decided against the Medal of Honor because, unlike many medal recipients, Erevia wasn't wounded in the battle.

Still, MacFarland said, "I was not convinced that it was not as a result of my inadequacy as a writer."

The Medal of Honor has been awarded to more than 3,400 recipients since it was established during the Civil War. Of those, 74 are living, according to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society. The medal is bestowed "only to the bravest of the brave," according to the Army.

Unbeknown to MacFarland or Erevia, Congress in a 2002 defense bill ordered a Pentagon review to determine whether discrimination prevented Jewish and Latino veterans from receiving the medal. The Pentagon examined the records of more than 6,000 Distinguished Service Cross recipients to determine whether the award should be upgraded.

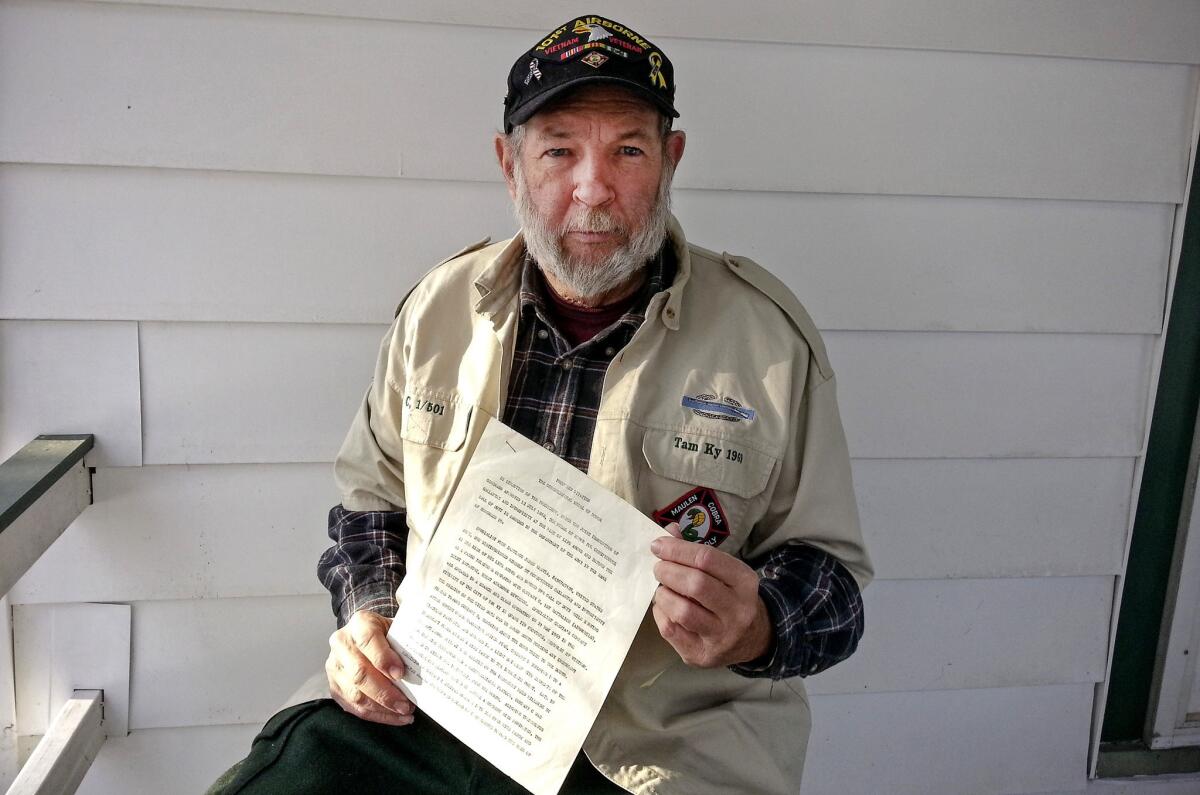

MacFarland, now 68, holds a copy of the recommendation he wrote in 1969. Erevia was denied the medal at the time, and MacFarland blamed himself, believing perhaps he did a poor job with the nomination. But a Pentagon review decades later determined the rejection was due to discrimination. (Les Gamble) More photos

Last summer, Erevia was surprised to receive a telephone call from a military officer who told him to expect a call from somebody at the White House. A few days later, he was called again and told to stay close to the phone.

When the call came, a woman announced that the president of the United States was on the line. "It was a short conversation," Erevia said. "He said that I deserved the Medal of Honor. He said that, for some reason, I was overlooked, but that he was making it right. I said, 'Thank you very much, sir.'"

The Pentagon has not released its Medal of Honor review, but in February the White House announced that to correct a historic injustice, the Medal of Honor would be awarded to 24 veterans from World War II, Korea and Vietnam. They include Erevia and 16 other Latinos, one African American and a Jew.

Erevia is one of three surviving veterans who will receive the medal next week. He is honored, Erevia said, even if the wait lasted decades.

"I'm just glad I'm getting it while I'm alive," he said.

Erevia, left, Sgt. 1st Class Jose Rodela and Staff Sgt. Melvin Morris, who all served in the Army during the Vietnam War, are the only living soldiers who will receive the Medal of Honor on March 18. Twenty-one recipients, from World War II, Korea and Vietnam, will be honored posthumously. (U.S. Army / Associated Press) More photos

MacFarland heard the news from an Army friend. "I can't describe how great that made me feel," he said.

He hadn't failed after all, and there is a good chance that when the citation is read Tuesday at the White House ceremony, it will include lines MacFarland composed in that tent long ago.

Since the announcement, Erevia has received a lot of attention, including letters from strangers praising his valor.

One letter stood out.

It was from MacFarland. He congratulated Erevia and shared with him the "heavy burden" that he carried around all these years.

"It made me cry," Erevia said.

The two may finally meet again at a Company C reunion this year.

Follow Richard Simon(@richardsimon11) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Bangladesh women find liberty in hard labor

I like it here, I make my own decisions. I can earn money and help my family.””

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.