Trump administration opens a new shelter for migrant youth — just as their numbers drop

Reporting from Carrizo Springs, Texas — By the time a new federal shelter opened for migrant youths in this central Texas oilfield town last month, hundreds of children had been stuck for weeks in squalid Border Patrol stations.

But now the number of child migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border has decreased, the backlog in Border Patrol stations has eased and it’s not clear why the government is relying on such expensive shelters as the one in Carrizo Springs. On Wednesday, it had 749 staff on duty, but only 212 of the 1,000 beds were occupied.

Daily cost: $775 per child.

“Maybe it’s too much too late. It should have been here in May,” said Kevin Dinnin, president of the San Antonio-based nonprofit BCFS, which the government pays to run the Carrizo Springs shelter.

The number of children arriving at the border unaccompanied by an adult spiked in May to 11,875, more than double the number of migrant children six months earlier. Last month, 35% fewer children arrived at the border, 7,684 total, part of an overall decrease in children and families migrating that immigration officials attribute to the summer heat and a migrant crackdown by officials in Mexico.

By law, migrant children who arrive at the border without an adult are supposed to be transferred from Border Patrol stations to the Department of Health and Human Services within 72 hours for placement in shelters and, eventually, with their parents or other sponsors. But last month, many were held by the Border Patrol longer than that in deteriorating conditions, according to a Homeland Security inspector general’s report and migrant advocates.

The Border Patrol is part of the Department of Homeland Security, which is a separate agency from Health and Human Services.

During a tour for reporters Wednesday, conditions at the Carrizo Springs shelter for youth ages 13 to 17 appeared to be in marked contrast to Border Patrol station detention centers in recent weeks. The well-staffed clinic, stocked with children’s vaccines, was empty — children had suffered only minor injuries and illnesses since arriving, staff said.

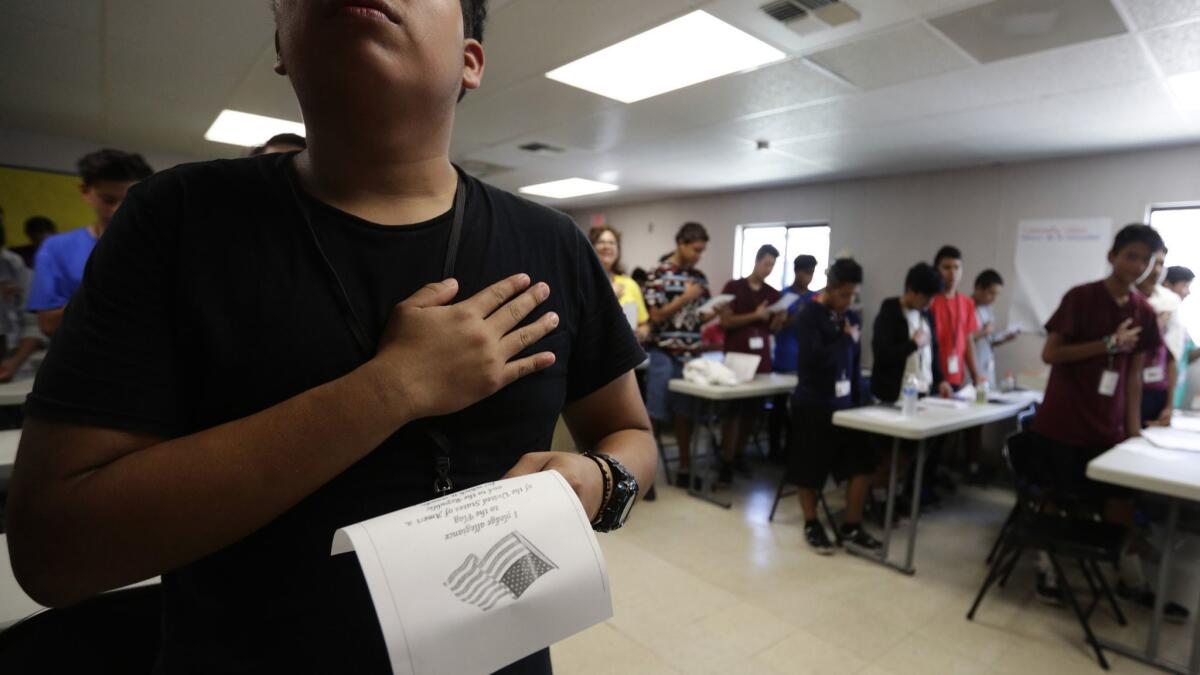

Unlike Border Patrol stations where children sleep in cells on pallets or concrete floors, at the shelter they slept on bunk beds in air-conditioned trailers. In other trailers, youths attend classes daily and can meet with lawyers. There’s an enormous dining hall and a soccer field.

But it’s difficult to know how youth at the shelters feel. Reporters at Carrizo Springs were not allowed to interview them.

More than half are from Guatemala; the rest are mostly from Honduras and El Salvador. They’re allowed to decorate their rooms — some with construction-paper flags of their home countries — and can call home twice a week for 10 minutes at a time, said Mark Weber, a Health and Human Services spokesman who led the tour.

When a Times reporter attempted to talk to a 16-year-old girl making a call, and copied down the number she was calling, staff intervened and insisted the number be erased.

Border Patrol officials have blamed Health and Human Services for not making space for children who languished at Border Patrol stations unequipped to care for them long-term. But Weber disputed that, saying Health and Human Services has always had enough space for children transferred from the Border Patrol.

Why are migrants getting sick or dying on the border? »

He said Health and Human Services had taken “every child that was referred” by the Border Patrol, adding that as of Tuesday, the Border Patrol wasn’t holding any children longer than 72 hours.

The average number of migrant children in Health and Human Services shelters reached 14,226 in December. Then the number of children arriving at the border dropped. This week, 12,400 youth were in such shelters nationwide, and more were leaving than arriving, Weber said. They spent an average of 45 days in shelters, compared with 89 days in December. At Carrizo Springs, Dinnin said the goal was to release children within a month.

Health and Human Services has stopped sending youths to its other large emergency shelter in Homestead, Fla., which housed 2,000 this week. It has been the scene of protests by, among others, Democratic presidential hopefuls Sen. Elizabeth Warren and former Rep. Beto O’Rourke.

In May, migrant advocates who visited the shelter filed a complaint with a federal judge in Los Angeles alleging some children had been held there for more than 140 days, grown depressed and were cutting themselves. The judge has ordered lawyers representing the children and the government to attend mediation and report back by Friday.

“We’re ready to close Homestead as soon as we can. We don’t need it,” Weber said.

It’s not clear whether Health and Human Services will still open a planned 1,400-bed shelter at an Army post in Ft. Sill, Okla., that BCFS was planning to run, Weber said. That shelter has also been the scene of recent protests by migrant advocates who oppose the mass detention of children.

Dinnin, who runs the Carrizo Springs shelter, said such facilities “should be a last resort.” His nonprofit has a $300-million grant to run the shelter through December, but it could close sooner if it’s not needed, Weber said.

He said Health and Human Services started using massive temporary shelters after a migrant influx in 2014, when the agency ran out of space, released some youth to traffickers and “failed children.”

But, he acknowledged, “This expansion/contraction model doesn’t seem to be working anymore.”

Instead, he said Health and Human Services has issued contracts for at least five shelters to house 2,500 youth in Atlanta, Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio or Phoenix. The sites would cost less than emergency shelters, about $250 a day. While the shelters may sit empty at first, Weber said, when the next surge of child migrants starts, “We’ll be prepared.”

ALSO:

Facing Trump’s asylum limits, refugees from as far as Africa languish in a Mexican camp

Migrants contemplate dangerous crossings despite border deaths and detention conditions

He voted for Trump. Now he and his wife raise their son from opposite sides of the border

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.