Across U.S., bridges crumble as repair funds fall short

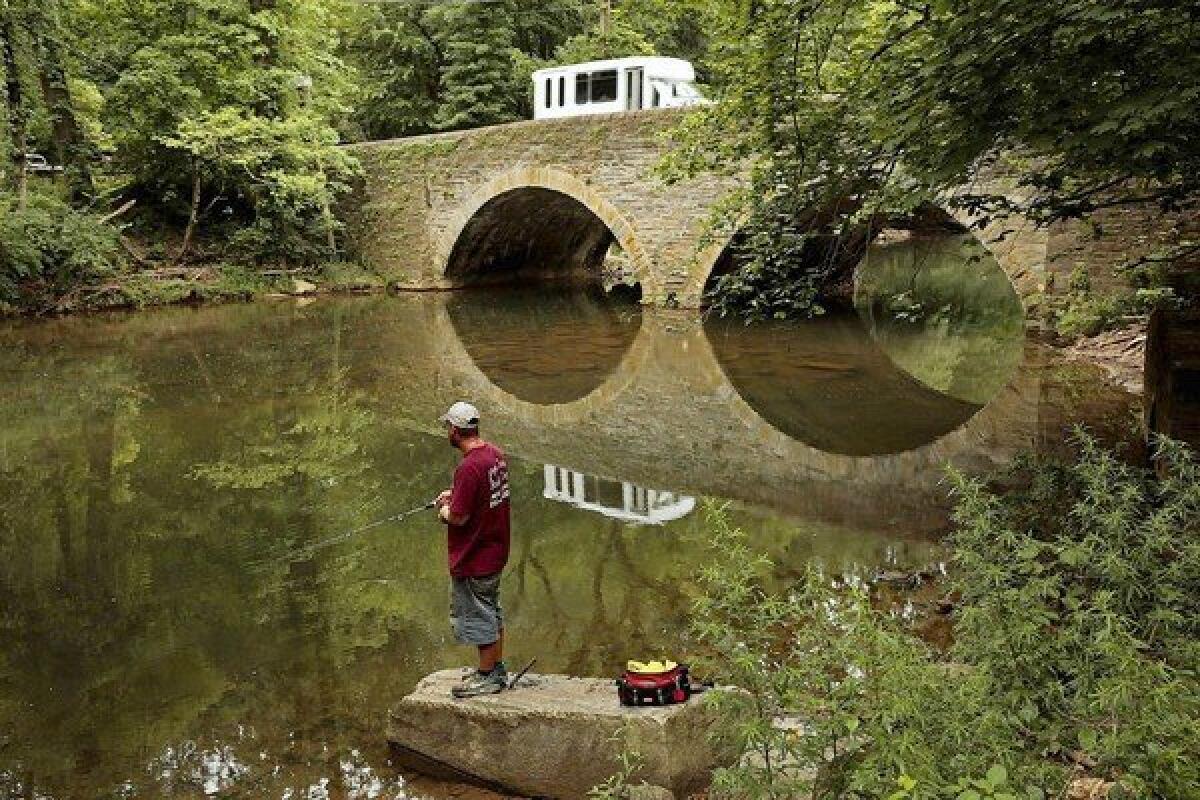

SCHWENKSVILLE, Pa. — Engineers think that three of the bridges closest to Dave Wisler’s home are about ready to collapse.

One, a picturesque one-lane structure built in 1893, became so perilous it was closed last summer, and the county doesn’t have the money to fix it. Another bridge, just down the road, is well-known for the concrete that chips off the bottom as children play in the creek below — it’s currently under repair.

Traffic was diverted to a third bridge nearby, but some drivers noticed a worrying humming noise as they drove over it, and their windows rattled. Authorities have since found that bridge is too dangerous to drive over too, and don’t know when they’ll be able to reopen it.

To get to a barn that he’s restoring across the river, about 300 yards away, Wisler now has to drive 15 minutes past homes and parks and blinking orange and white construction signs.

“I can’t get there from here,” said Wisler, peering over the small creek that winds through this rural town just outside Philadelphia.

America’s roads and bridges have been eroding for decades, but the deeper they fall into disrepair, the less money there is to fix them. First, the recession crippled local budgets, cutting the money available for transportation projects. As states began to recover, the federal government adopted its own mandatory budget cuts via sequestration. Then last month, the federal legislation that annually funds transportation projects across the country hit a roadblock of Republican opposition that throttled multibillion-dollar transportation bills in the House and Senate.

The new political deadlock in Washington, D.C., comes as the Federal Highway Administration estimates that bridge and road repair needs have escalated to $20.5 billion a year.

Every day, U.S. commuters are taking more than 200 million trips across deficient bridges, according to a variety of analyses, and at least 8,000 bridges across the country are both “structurally deficient” and “fracture critical” — engineering terms for bridges that could fail if even a single component breaks.

“These bridges will all eventually fall down,” said Barry LePatner, a construction attorney who has documented bridge deficiencies in all 50 states.

Officials from several states, including Pennsylvania, have warned that without substantial new federal funding of the kind recently roadblocked in Congress, they may be forced to close many of their deficient bridges, potentially preventing cars, emergency vehicles and school buses from getting to entire neighborhoods. Some states are looking for their own ways to raise money. Eight states raised their gas taxes last month, including Wyoming, which has a Republican-dominated legislature.

In California, the place that pioneered a car-friendly lifestyle, thousands of bridges built decades ago are in need of repair. Bridges last about 50 years, and in California, most average around 44 years, with more than 8,000 bridges more than half a century old. In Los Angeles County alone, 16 bridges are in the highest-risk category, aging and subject to collapse with the failure of a single component. They include a part of the 10 Freeway over the Los Angeles River, a section of Almansor Street over the same freeway and a segment of Ocean Boulevard in Long Beach.

Equally threatened is a portion of Tustin Avenue that takes about 221,000 vehicles a day over the 91 Freeway in Anaheim.

California and other states with growing populations also face the new infrastructure demands that come with the influx of more cars and trains. Analysts say the state needs to spend $750 billion on infrastructure projects in the next 10 years to remain competitive.

Some of the most important bridge links in the country are now threatened by age. The longest bridge in New York, the Tappan Zee Bridge over the Hudson River, 25 miles north of Manhattan and a crucial link for the interstate highway system in the New York metropolitan area, is potentially subject to catastrophic failure, engineers say. Yet replacing it will cost at least $5.2 billion — and as much as $16 billion with transit options.

The potential repercussions of ignoring the funding shortage are huge, as recent bridge collapses in Minnesota and Washington state have shown. In 2007, Minnesota’s fourth-busiest bridge, which spanned the Mississippi River, collapsed, killing 13. Engineers found that additional weight placed on the bridge from construction had exacerbated a design flaw. And earlier this year in Washington, days after the state’s governor pleaded for a transportation tax increase, a bridge on Interstate 5 plunged into the Skagit River after being hit by a truck.

“It is only a matter of time,” said LePatner, whose website, SaveOurBridges.com, maps these 8,000 deficient bridges, including two of those recently closed near Wisler’s home. “Because these bridges are fragile and the public is unsafe driving over them.”

The state with the biggest backlog of eroding bridges is Pennsylvania, where an estimated 1 in 4 bridges is deemed structurally deficient by engineering standards. It’s a fact that’s evident to Terrell Davis, 31, a North Philadelphia resident who walks every day across a bridge on Erie Avenue that appears to be on the brink of collapse. Davis can peek through holes in the rusting metal structure to see a swamp hundreds of feet below. Parts of the beams are so rusted that they’ve become detached from the bridge and hang in open air.

“All it needs is something too heavy to go across here and this whole thing will collapse,” Davis said as a city bus sped past, bumping over the cracks in the concrete and making the bridge shudder.

A 2010 inspection found that this bridge was in both “serious” and “poor” condition, scoring only 3 out of 9 for its substructure and 4 out of 9 for its deck. The inspection found the bridge was structurally deficient and recommended it be repaired. About 20,000 cars go over the bridge every day.

But like many cities throughout the country, Philadelphia doesn’t have the money to repair every bridge that needs to be fixed.

“The total funding stream, in reality, is not keeping up with demands,” said David Perri, Philadelphia’s acting streets commissioner. “Our backlog of bridge needs is approximately $300 million, and that’s a sum of money no local municipality can afford on its own.”

Part of the problem is timing. Many of the nation’s roads and bridges were built during the Eisenhower administration in the 1950s and are now all coming due for repair at the same time. Cold weather and freezes in the Northeast can exacerbate problems, said Michael Boyer of the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission.

But the bigger issue is funding. Money to fix roads and bridges comes from the federal government, which raises funds through a gas tax. The gas tax has not been raised since 1993, and in an era of anti-tax rhetoric in Washington, advocates say there’s little hope of seeing an increase anytime soon. The rise of fuel-efficient vehicles and hybrids is also making the gas tax less lucrative.

Big hits to state budgets during the recession also cut back funding streams, as competition from Brazil and China drove up the price of cement and asphalt. In many cases, structures deteriorated more quickly because they weren’t being maintained.

“What’s happening is that there’s a lot of demand for government resources,” said Martin Pietrucha, director of the Larson Pennsylvania Transportation Institute at Penn State. “I’m all for Grandma getting her lunch rather than fixing a pothole, but it just gets to be a bigger and bigger problem.”

Political bickering hasn’t helped matters. Congress usually passes a six-year transportation bill, but last year it passed just a two-year transportation bill. In that bill, Congress also cut a dedicated bridge maintenance program and scrapped a system of accountability for bridge repair. Last month, Senate Republicans blocked a $54-billion transportation measure because it exceeded previously set spending limits. The House did not even vote on a $44-billion version of the bill because there were clearly not enough votes to pass it.

“We’re at something of a fiscal cliff for transportation these days,” said David Goldberg, a spokesman for the nonprofit group Transportation for America. “The needs are growing, but the traditional funding source has remained static and is projected to decline.”

Richard Cobb knows the cost of ignoring much-needed infrastructure repairs. His truck fell into a pothole on 61st Street in West Philadelphia, cracking his tire rim. He recently took the truck to the shop, and is depending on his elderly father for rides while he waits for it to be fixed.

“This place has the raggediest roads in the country,” he said, holding up his cracked rim. “And they claim they don’t have money to fix them.”

The cost is more than just economic. Pat Bush, who lives next door to Dave Wisler, said she and her husband were trapped in their house without electricity during Superstorm Sandy because trees had blocked the road one way, and the closed bridge blocked it in another. With three bridges now closed for repairs, neighbors worry that firetrucks and school buses won’t be able to reach them.

“We’re kind of trapped here,” said Royce Yoder, another neighbor. “If a fire happens, by the time the trucks can get here, we’re just a pile of rubble.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.