Enrique’s Journey | Chapter One: The Boy Left Behind

The boy does not understand.

His mother is not talking to him. She will not even look at him. Enrique has no hint of what she is going to do.

Lourdes knows. She understands, as only a mother can, the terror she is about to inflict, the ache Enrique will feel and finally the emptiness.

What will become of him? Already he will not let anyone else feed or bathe him. He loves her deeply, as only a son can. With Lourdes, he is a chatterbox. “Mira, Mami. Look, Mom,” he says softly, asking her questions about everything he sees. Without her, he is so shy it is crushing.

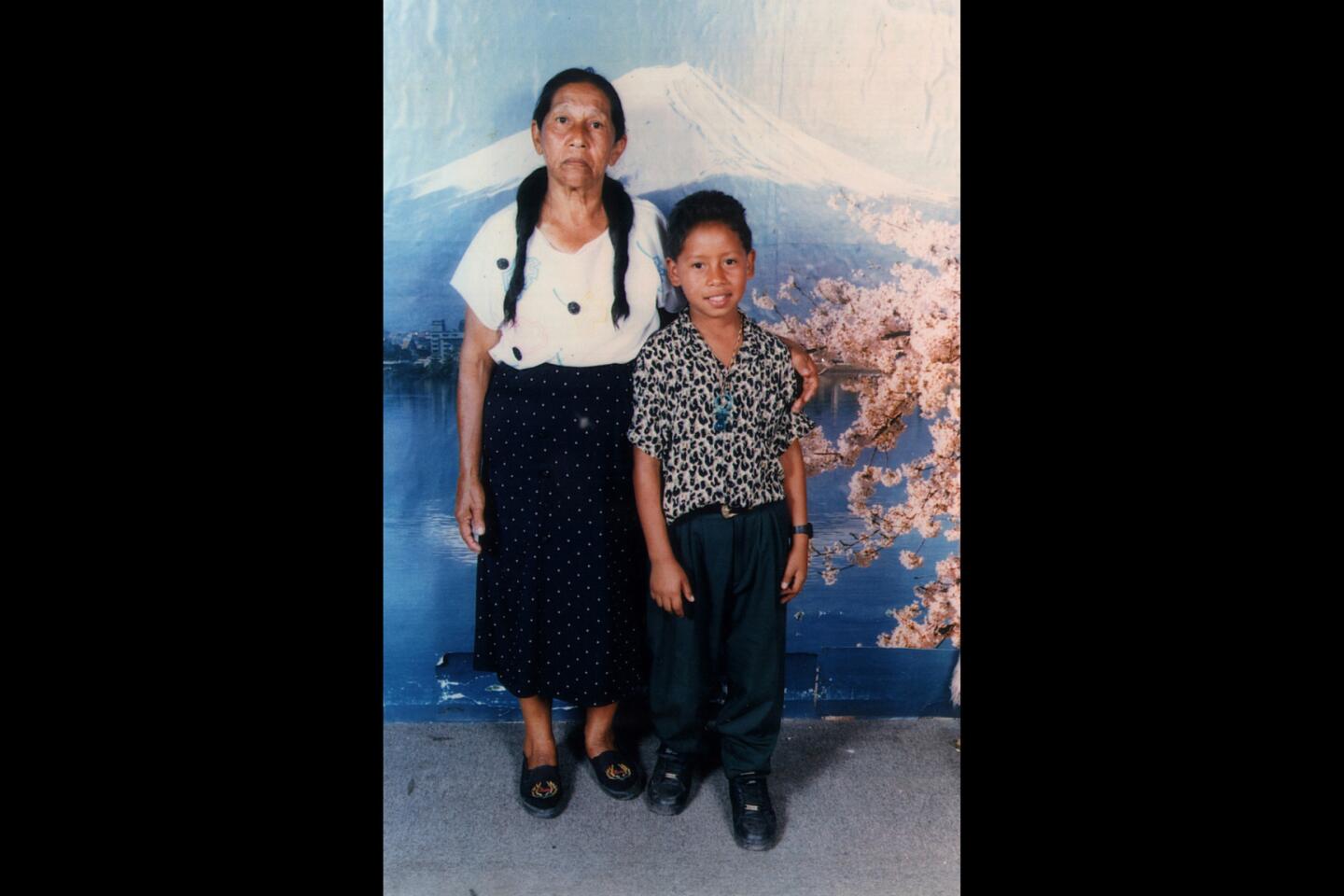

Slowly, she walks out onto the porch. Enrique clings to her pant leg. Beside her, he is tiny. Lourdes loves him so much she cannot bring herself to say a word. She cannot carry his picture. It would melt her resolve. She cannot hug him. He is 5 years old.

They live on the outskirts of Tegucigalpa, in Honduras. She can barely afford food for him and his sister, Belky, who is 7. Lourdes, 24, scrubs other people’s laundry in a muddy river. She fills a wooden box with gum and crackers and cigarettes, and she finds a spot where she can squat on a dusty sidewalk next to the downtown Pizza Hut and sell the items to passersby. The sidewalk is Enrique’s playground.

They have a bleak future. He and Belky are not likely to finish grade school. Lourdes cannot afford uniforms or pencils. Her husband is gone. A good job is out of the question. So she has decided: She will leave. She will go to the United States and make money and send it home. She will be gone for one year, less with luck, or she will bring her children to be with her. It is for them she is leaving, she tells herself, but still, she feels guilty.

She kneels and kisses Belky and hugs her tightly.

Then Lourdes turns to her own sister. If she watches over Belky, she will get a set of gold fingernails from El Norte.

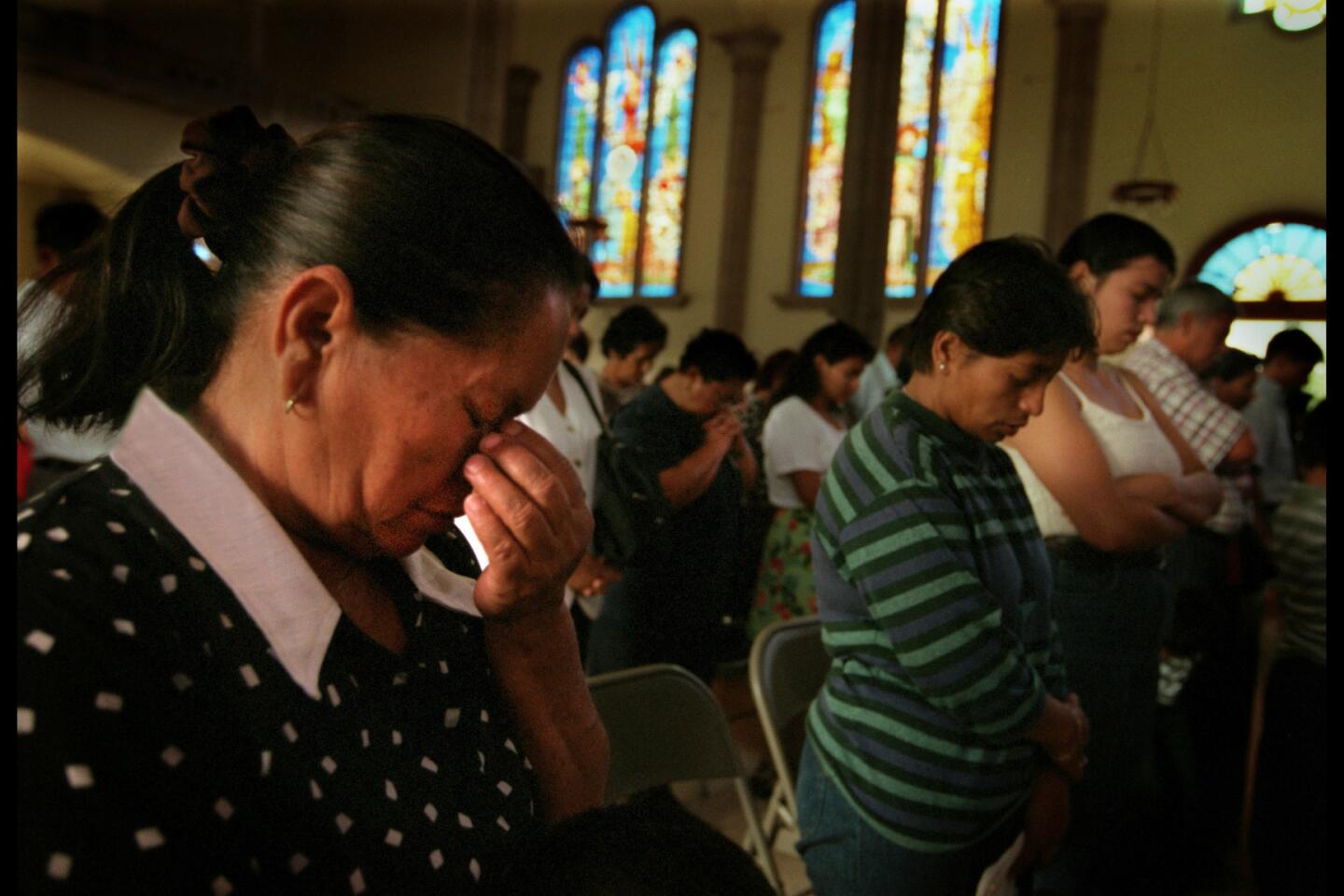

But Lourdes cannot face Enrique. He will remember only one thing that she says to him: “Don’t forget to go to church this afternoon.”

It is Jan. 29, 1989. His mother steps off the porch.

She walks away.

“Donde esta mi mami?” Enrique cries, over and over. “Where is my mom?”

::

His mother never returns, and that decides Enrique’s fate. As a teenager--indeed, still a child--he will set out for the U.S. on his own to search for her. Virtually unnoticed, he will become one of an estimated 48,000 children who enter the United States from Central America and Mexico each year, illegally and without either of their parents. Roughly two-thirds of them will make it past the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Many go north seeking work. Others flee abusive families. Most of the Central Americans go to reunite with a parent, say counselors at a detention center in Texas where the INS houses the largest number of the unaccompanied children it catches. Of those, the counselors say, 75% are looking for their mothers. Some children say they need to find out whether their mothers still love them. A priest at a Texas shelter says they often bring pictures of themselves in their mothers’ arms.

The journey is hard for the Mexicans but harder still for Enrique and the others from Central America. They must make an illegal and dangerous trek up the length of Mexico. Counselors and immigration lawyers say only half of them get help from smugglers. The rest travel alone. They are cold, hungry and helpless. They are hunted like animals by corrupt police, bandits and gang members deported from the United States. A University of Houston study found that most are robbed, beaten or raped, usually several times. Some are killed.

They set out with little or no money. Thousands, shelter workers say, make their way through Mexico clinging to the sides and tops of freight trains. Since the 1990s, Mexico and the United States have tried to thwart them. To evade Mexican police and immigration authorities, the children jump on and off the moving train cars. Sometimes they fall, and the wheels tear them apart.

They navigate by word of mouth or by the arc of the sun. Often, they don’t know where or when they’ll get their next meal. Some go days without eating. If a train stops even briefly, they crouch by the tracks, cup their hands and steal sips of water from shiny puddles tainted with diesel fuel. At night, they huddle together on the train cars or next to the tracks. They sleep in trees, in tall grass or in beds made of leaves.

Some are very young. Mexican rail workers have encountered 7-year-olds on their way to find their mothers. A policeman discovered a 9-year-old boy four years ago near the downtown Los Angeles tracks. “I’m looking for my mother,” he said. The youngster had left Puerto Cortes in Honduras three months before, guided only by his cunning and the single thing he knew about her: where she lived. He asked everyone: “How do I get to San Francisco?”

Typically the children are teenagers. Some were babies when their mothers left; they know them only by pictures sent home. Others, a bit older, struggle to hold on to memories: One has slept in her mother’s bed; another has smelled her perfume, put on her deodorant, her clothes. One is old enough to remember his mother’s face, another her laugh, her favorite shade of lipstick, how her dress felt as she stood at the stove patting tortillas.

Many, including Enrique, begin to idealize their mothers. In their absence, these mothers become larger than life. Although the women struggle to pay rent and eat in the United States, in the imaginations of their children back home they become deliverance itself, the answer to every problem. Finding them becomes the quest for the Holy Grail.

::

Confusion

Enrique is bewildered. Who will take care of him now that his mother is gone? For two years, he is entrusted to his father, Luis, from whom his mother had been separated for three years.

Enrique clings to his daddy, who dotes on him. A bricklayer, his father takes Enrique to work and lets him help mix mortar. They live with Enrique’s grandmother. His father shares a bed with him and brings him apples and clothes. Every month, Enrique misses his mother less, but he does not forget her.

“When is she coming for me?” he says.

Lourdes crosses into the United States in one of the largest immigrant waves in the country’s history. She enters through a rat-infested Tijuana sewage tunnel and makes her way to Los Angeles. She moves in with a Beverly Hills couple to take care of their 3-year-old daughter. Every morning as the couple leave for work, the little girl cries for her mother. Lourdes feeds her breakfast and thinks of Enrique and Belky. “I’m giving this girl food,” she says to herself, “instead of feeding my own children.” After seven months, she cannot take it. She quits and moves to a friend’s place in Long Beach.

Boxes arrive in Tegucigalpa bearing clothes, shoes, toy cars, a Robocop doll, a television. Lourdes writes: Do they like the things she is sending? She tells Enrique to behave, to study hard. She has hopes for him: graduation from high school, a white-collar job, maybe as an engineer. She says she loves him.

She will be home soon, his grandmother says.

But his mother does not come. Her disappearance is incomprehensible. Enrique’s bewilderment turns to confusion and then to adolescent anger.

When Enrique is 7, his father brings home a woman. To her, Enrique is an economic burden. One morning, she spills hot cocoa and burns him. His father throws her out. But their separation is brief. Enrique’s father bathes, dresses, splashes on cologne and follows her. Enrique tags along and begs to stay with him. But his father tells him to go back to his grandmother.

His father begins a new family. Enrique sees him rarely, usually by chance. “He doesn’t love me,” he tells Belky. “I don’t have a dad.”

For Belky, their mother’s disappearance is just as distressing. She lives with Aunt Rosa Amalia, one of her mother’s sisters. On Mother’s Day, Belky struggles through a celebration at school. That night she cries quietly, alone in her room. Then she scolds herself. She should thank her mother for leaving; without the money she sends for books and uniforms, Belky could not even attend school. She commiserates with a friend whose mother has also left. They console each other. They know a girl whose mother died of a heart attack. At least, they say, ours are alive.

But Rosa Amalia thinks the separation has caused deep emotional problems. To her, it seems that Belky struggles with an unavoidable question: How can I be worth something if my mother left me?

Confused by all of this, Enrique turns to his grandmother. Alone now, he and his father’s elderly mother share a shack 30 feet square. Maria Marcos built it herself of wooden slats. Enrique can see daylight in the cracks. It has four rooms, three without electricity. There is no running water. Gutters carry rain off the patched tin roof into two barrels. A trickle of cloudy white sewage runs past the front gate. On a well-worn rock nearby, Enrique’s grandmother washes musty used clothing she sells door to door. Next to the rock is the latrine--a concrete hole. Beside it are buckets for bathing.

The shack is in Carrizal, one of Tegucigalpa’s poorest neighborhoods. Sometimes Enrique looks across the rolling hills to the neighborhood where he and his mother had lived and where Belky still lives with their mother’s family. They are six miles apart. They hardly ever visit.

Lourdes sends Enrique $50 a month, occasionally $100, sometimes nothing. It is enough for food, but not for school clothes, fees, notebooks or pencils, which are expensive in Honduras. There is never enough for a birthday present. But Grandmother Maria hugs him and wishes him a cheery “Feliz cumpleanos!”

“Your mom can’t send enough,” she says, “so we both have to work.”

After school, Enrique sells tamales and plastic bags of fruit juice from a bucket hung in the crook of his arm.

“Tamarindo! Pina!” he shouts.

After he turns 10, he rides buses alone to an outdoor food market. He stuffs tiny bags with nutmeg, curry and paprika, then seals them with hot wax. He pauses at big black gates in front of the market and calls out, “Va a querer especias? Who wants spices?” He has no vendor’s license, so he keeps moving, darting between wooden carts piled with papayas.

Grandmother Maria cooks plantains, spaghetti and fresh eggs. Now and then, she kills a chicken and prepares it for him. In return, when she is sick, Enrique rubs medicine on her back. He brings water to her in bed.

Every year on Mother’s Day, he makes a heart-shaped card at school and presses it into her hand.

“I love you very much, Grandma,” he writes.

But she is not his mother. Enrique longs to hear Lourdes’ voice. His only way of talking to her is at the home of a cousin, Maria Edelmira Sanchez Mejia, one of the few family members who have a telephone. His mother seldom calls. One year she does not call at all.

“I thought you had died, girl!” Maria Edelmira says.

Better to send money, Lourdes replies, than burn it up on the phone. But there is another reason she hasn’t called. A boyfriend from Honduras had joined her in Long Beach. She unintentionally became pregnant, and now he has been deported. She and her new daughter, Diana, 2, are living in a garage, sometimes on emergency welfare. There are good months, though, when she can earn $1,000 to $1,200 cleaning offices and homes. Scrubbing floors bloodies her knees, but she takes extra jobs, one at a candy factory for $2.25 an hour. Besides the cash for Enrique, every month she sends $50 each to her mother and Belky.

It is no substitute for her presence. Belky, now 9, is furious about the new baby. Their mother might lose interest in her and Enrique, and the baby will make it harder to wire money and save so she can bring them north.

For Enrique, each telephone call grows more strained. Because he lives across town, he is not often lucky enough to be at Maria Edelmira’s house when his mother phones. When he is, their talk is clipped and anxious.

Quietly, however, one of these conversations plants the seed of an idea. Unwittingly, Lourdes sows it herself.

“When are you coming home?” Enrique asks.

She avoids an answer. Instead, she promises to send for him very soon.

It had never occurred to him: If she will not come home, then maybe he can go to her. Neither he nor his mother realizes it, but this kernel of an idea will take root. From now on, whenever Enrique speaks to her, he ends by saying, “I want to be with you.”

On the telephone, Lourdes’ own mother begs her, “Come home.”

Pride forbids it. How can she justify leaving her children if she returns empty-handed? Four blocks from her mother’s place is a white house with purple trim. It takes up half a block behind black iron gates. The house belongs to a woman whose children went to Washington, D.C., and sent her the money to build it. Lourdes cannot afford such a house for her mother, much less herself.

But she develops a plan. She will become a resident and bring her children to the United States legally. Three times, she hires storefront immigration counselors who promise help. She pays them a total of $3,850. A woman in Long Beach, whose house she cleans, agrees to sponsor her residency. But the counselors never deliver.

“I’ll be back next Christmas,” she tells Enrique.

Christmas arrives, and he waits by the door. She does not come. Every year, she promises. Each year, he is disappointed. Confusion finally grows into anger. “I need her. I miss her,” he tells his sister. “I want to be with my mother. I see so many children with mothers. I want that.”

One day, he asks his grandmother, “How did my mom get to the United States?”

Years later, Enrique will remember his grandmother’s reply--and how another seed was planted: “Maybe,” Maria said, “she went on the trains.”

“What are the trains like?”

“They are very, very dangerous,” his grandmother said. “Many people die on the trains.”

When Enrique is 12, Lourdes tells him yet again that she will come home.

“Si,” he replies. “Va, pues. Sure. Sure.”

Enrique senses a truth: Very few mothers ever return. He tells her that he doesn’t think she is coming back. To himself, he says, “It’s all one big lie.”

Lourdes does consider hiring a smuggler to bring the children but fears the danger. The coyotes, as they are called, are often alcoholics or drug addicts. Sometimes they abandon their charges. “Do I want to have them with me so badly,” she asks herself, “that I’m willing to risk their losing their lives?” Besides, she does not want Enrique to come to California. There are too many gangs, drugs and crimes.

In any event, she has not saved enough. The cheapest coyote, immigrant advocates say, charges $3,000 per child. Female coyotes want up to $6,000. A top smuggler will bring a child by commercial flight for $10,000.

Enrique despairs. He will simply have to do it himself. He will go find her. He will ride the trains.

“I want to come,” he tells her.

Don’t even joke about it, she says. It is too dangerous. Be patient.

::

Rebellion

Now Enrique’s anger boils over. He refuses to make his Mother’s Day card at school. He begins hitting other kids. He lifts the teacher’s skirt.

He stands on top of the teacher’s desk and bellows, “Who is Enrique?”

“You!” the class replies.

Three times, he is suspended. Twice he repeats a grade. But Enrique never abandons his promise to study. Unlike half the children from his neighborhood, he completes elementary school. There is a small ceremony. A teacher hugs him and mutters, “Thank God, Enrique’s out of here.”

He stands proud in a blue gown and mortarboard. But nobody from his mother’s family comes to the graduation.

Now he is 14, a teenager. He spends more time on the streets of Carrizal, which is quickly becoming one of Tegucigalpa’s toughest neighborhoods. His grandmother tells him to come home early. But he plays soccer until midnight. He refuses to sell spices. It is embarrassing when girls see him peddle fruit cups or when they hear someone call him “the tamale man.”

He stops going to church.

“Don’t hang out with bad boys,” Grandmother Maria says.

“You can’t pick my friends!” Enrique replies. She is not his mother, he tells her, and she has no right to tell him what to do.

He stays out all night.

His grandmother waits up for him, crying. “Why are you doing this to me?” she asks. “Don’t you love me? I am going to send you away.”

“Send me! No one loves me.”

But she says she does love him. She only wants him to work and to be honorable, so that he can hold his head up high.

He replies that he will do what he wants.

Enrique has become her youngest child. “Please bury me,” she says. “Stay with me. If you do, all this is yours.” She prays that she can hold on to him until his mother sends for him. But her own children say Enrique has to go: She is 70, and he will bury her, all right, by sending her to the grave.

Sadly, she writes to Lourdes: You must find him another home.

To Enrique, it is another rejection. First his mother, then his father and now his grandmother.

Lourdes arranges for a brother, Marco Antonio Zablah, to take him in.

Her gifts arrive steadily. She is proud that her money pays Belky’s tuition at a private high school and eventually a college, to study accounting. Kids from poor neighborhoods almost never go to college.

Money from Lourdes helps Enrique too, and he realizes it. If she were here, he knows where he might well be: scavenging in the trash dump across town. Lourdes knows it too; as a girl, she herself worked the dump. Enrique knows children as young as 6 or 7 whose single mothers have stayed at home and who have had to root through the waste in order to eat.

Truck after truck rumbles onto the hilltop. Dozens of adults and children fight for position. Each truck dumps its load. Feverishly, the scavengers reach up into the sliding ooze to pluck out bits of plastic, wood and tin. The trash squishes beneath their feet, moistened by loads from hospitals, full of blood and placentas. Occasionally a child, with hands blackened by garbage, picks up a piece of stale bread and eats it. As the youngsters sort through the stinking stew, thousands of sleek, black buzzards soar in a dark, swirling cloud.

A year after Enrique goes to live with his uncle, Lourdes calls--this time from North Carolina. “California is too hard,” she says. “There are too many immigrants.” Employers pay poorly and treat them badly. Here people are less hostile. Work is plentiful. She works on an assembly line for $9.05 an hour--$13.50 when she works overtime--and waits tables. She has met someone, a house painter from Honduras, and they are moving in together.

Enrique misses her enormously. But Uncle Marco and his girlfriend treat him well. Marco is a money changer on the Honduran border, and his family, including a son, lives in a five-bedroom house in a middle-class neighborhood of Tegucigalpa. Uncle Marco gives Enrique a daily allowance, buys him clothes and sends him to a private military school.

Enrique runs errands for his uncle, washes his five cars, follows him everywhere. His uncle pays as much attention to him as he does his own son, if not more. “Negrito,” he calls him fondly, because of his dark skin. Although he is in his teens, Enrique is small, just shy of 5 feet, even when he straightens up from a slight stoop. He has a big smile and perfect teeth.

His uncle trusts him, even to make bank deposits. He tells Enrique, “I want you to work with me forever.”

One week, as his uncle’s security guard returns from trading Honduran lempiras, robbers drag the guard off a bus and kill him. The guard has a son 23 years old, and the slaying impels the young man to go to the United States. He comes back before crossing the Rio Grande and tells Enrique about riding on trains, leaping off rolling freight cars and dodging la migra, Mexican immigration agents.

Because of the security guard’s murder, Marco swears that he will never change money again. A few months later, though, he gets a call. For a large commission, would he exchange $50,000 in lempiras on the border with El Salvador? Uncle Marco promises that this will be the last time.

Enrique wants to go with him.

But his uncle says he is too young. He takes one of his own brothers instead.

Robbers riddle their car with bullets. Enrique’s uncles careen off the road. The thieves shoot Uncle Marco three times in the chest and once in the leg. They shoot his brother in the face. Both die.

Now Uncle Marco is gone.

In nine years, Lourdes has saved $700 toward bringing her children to the United States. Instead, she uses it to help pay for her brothers’ funerals.

Within days, Uncle Marco’s girlfriend sells Enrique’s television, stereo and Nintendo game--all gifts from Marco. Without telling him why, she says, “I don’t want you here anymore.” She puts his bed out on the street.

::

Addiction

Enrique, now 15, gathers his clothing and goes to his maternal grandmother.

“Can I stay here?” he asks.

This had been his first home, the small stucco house where he and Lourdes lived until Lourdes stepped off the front porch and left. His second home was the wooden shack where he and his father lived with his father’s mother, until his father found a new wife and left. His third home was the comfortable house where he lived with his Uncle Marco.

Now he is back where he began. Seven people live here already: his grandmother, Agueda Amalia Valladares; two divorced aunts; and four young cousins. They are poor. “We need money just for food,” says his grandmother, who suffers from cataracts. Nonetheless, she takes him in.

She and the others are consumed by the slayings of the two uncles; they pay little attention to Enrique. He grows quiet, introverted.

He does not return to school.

At first, he shares the front bedroom with an aunt, Mirian Liliana Aguilera, 26. One day she awakens at 2 a.m. Enrique is sobbing quietly in his bed, cradling a picture of Uncle Marco in his arms. Enrique cries off and on for six months. His uncle loved him; without his uncle, he is lost.

Grandmother Agueda sours quickly on Enrique. She grows angry when he comes home late, knocking on her door, rousing the household. About a month later, Aunt Mirian wakes up again in the middle of the night. This time she smells acetone and hears the rustle of plastic. Through the dimness, she sees Enrique in his bed, puffing on a bag. He is sniffing glue.

Enrique is banished to a tiny stone building seven feet behind the house but a world away. It was once a cook shack, where his grandmother prepared food on an open fire. Its walls and ceiling are charred black. It has no electricity. The wooden door pries only partway open, and the single window has no glass, just bars. A few feet beyond is his privy--a hole with a wooden shanty over it.

The stone hut becomes his home.

Now Enrique can do whatever he wants. If he is out all night, no one cares. But to him, it feels like another rejection.

Nearby is a neighborhood called El Infiernito, or Little Hell, controlled by a street gang, the Mara Salvatrucha. Some MS have been U.S. residents, living in Los Angeles until 1996, when a federal law began requiring judges to deport them if they committed serious crimes. Now they are active throughout much of Central America and Mexico. Here in El Infiernito, they carry chimbas, guns fashioned from plumbing pipes, and they drink charamila, diluted rubbing alcohol. They ride the buses, robbing passengers.

Enrique and a friend, Jose del Carmen Bustamante, 16, venture into El Infiernito to buy marijuana. It is dangerous. On one occasion, Jose is threatened by a man who wraps a chain around his neck. The boys never linger. They take their joints partway up a hill to a billiard hall, where they sit outside smoking and listening to the music that drifts through the open doors.

With them are two other friends. Both have tried to ride freight trains to El Norte. One is known as El Gato, the cat. He talks about migra agents shooting over his head and how easy it is to be robbed by bandits. In Enrique’s marijuana haze, train-riding sounds like an adventure.

He and Jose resolve to try it soon.

Some nights, at 10 or so, they climb a steep, winding path to the top of another hill. Hidden beside a wall scrawled with graffiti, they inhale glue late into the night. One day, Enrique’s girlfriend, Maria Isabel Caria Duron, 17, turns a street corner and bumps into him. She is overwhelmed. He smells like an open can of paint.

“What’s that?” she asks, reeling away from the fumes. “Are you on drugs?’’

“No!” Enrique says.

He tries to hide his habit. He dabs a bit of glue into a plastic bag and stuffs it into a pocket. Alone, he opens the end over his mouth and inhales, pressing the bottom of the bag toward his face, pushing the fumes into his lungs.

Belky notices cloudy yellow fingerprints on Maria Isabel’s jeans: glue, a remnant of Enrique’s embrace.

Maria Isabel sees him change. His mouth is sweaty and sticky. He is jumpy and nervous. His eyes grow red. Sometimes they are glassy, half-closed. Other times he looks drunk. If she asks a question, the response is delayed. His temper is quick. On a high, he grows quiet, sleepy and distant. When he comes down, he becomes hysterical and insulting.

Drogo. Drug addict, one of his aunts calls him.

Sometimes he hallucinates that someone is chasing him. He imagines gnomes and fixates on ants. He sees a cartoon-like Winnie the Pooh soaring in front of him. He walks, but he cannot feel the ground. Sometimes his legs will not respond. Houses move. Occasionally, the floor falls.

For two particularly bad weeks, he doesn’t recognize family members. His hands tremble. He coughs black phlegm.

::

An education

Enrique marks his 16th birthday. All he wants is his mother. One Sunday, he and his friend Jose put train-riding to the test. They leave for El Norte.

At first, no one notices. They take buses across Guatemala to the Mexican border.

“I have a mom in the U.S.,” Enrique tells a guard.

“Go home,” the man replies.

They slip past the guard and make their way 12 miles into Mexico to Tapachula. There they approach a freight train near the depot. But before they can reach the tracks, police stop them. The officers rob them, the boys say later, but then let them go--Jose first, Enrique afterward.

They find each other and another train. Now, for the first time, Enrique clambers aboard. The train crawls out of the Tapachula station. From here on, he thinks, nothing bad can happen.

They know nothing about riding the rails.

Jose is terrified. Enrique, who is braver, jumps from car to car on the slow-moving train. He slips and falls--away from the tracks, luckily--and lands on a backpack padded with a shirt and an extra pair of pants.

He scrambles aboard again.

But their odyssey comes to a humiliating halt.

Near Tierra Blanca, a small town in Veracruz state, authorities snatch them from the top of a freight car. The officers take them to a cell filled with MS gangsters, then deport them. Enrique is bruised and limping, and he misses Maria Isabel. They find coconuts to sell for bus fare and go home.

::

A decision

Enrique sinks deeper into drugs. By mid-December, he owes his marijuana supplier 6,000 lempiras, about $400. He has only 1,000 lempiras. He promises the rest by midweek, but cannot keep his word. The following weekend, he encounters the dealer on the street.

The supplier accuses Enrique of lying and threatens to kill him.

Enrique pleads with him.

If Enrique doesn’t pay up, the dealer vows, he will kill Enrique’s sister. The dealer mistakenly thinks that Enrique’s cousin, Tania Ninoska Turcios, 18, is his sister. Both girls are finishing high school, and most of the family is away at a Nicaraguan hotel celebrating their graduation.

Enrique pries open the back door to the house where his Uncle Carlos Orlando Turcios Ramos and Aunt Rosa Amalia live. He hesitates. How can he do this to his own family? Three times, he walks up to the door, opens it, closes it and leaves. Each time, he takes another deep hit of glue.

Finally, he enters the house, picks open the lock to a bedroom door, then jimmies the back of his aunt’s armoire with a knife. He stuffs 25 pieces of her jewelry into a plastic bag and hides it under a rock near the local lumberyard.

At 10 p.m., the family returns to find the bedroom ransacked.

Neighbors say the dog did not bark.

“It must have been Enrique,” Aunt Rosa Amalia says. She calls the police. Uncle Carlos and several officers go to find him.

“Why did you do this? Why?” Aunt Rosa Amalia yells.

“It wasn’t me.” As soon as he says it, he flushes with shame and guilt. The police handcuff him. In their patrol car, he trembles and begins to cry. “I was drugged. I didn’t want to do it.” He tells the officers that a dealer wanting money had threatened to kill Tania.

He leads police to the bag of jewelry.

“Do you want us to lock him up?” the police ask.

Uncle Carlos thinks of Lourdes. They cannot do this to her. Instead, he orders Tania to stay indoors indefinitely, for her own safety.

But the robbery finally convinces Uncle Carlos that Enrique needs help. He finds him a $15-a-week job at a tire store. He eats lunch with him every day--chicken and homemade soup. He tells the family they must show him their love.

During the next month, January 2000, Enrique tries to quit drugs. He cuts back, but then he gives in. Every night, he comes home later. He looks at himself in disgust. He is dressing like a slob--his life is unraveling. He is lucid enough to tell Belky that he knows what he has to do.

He simply has to go find his mother.

Aunt Ana Lucia Aguilera agrees. She and Enrique have clashed for months. Ana Lucia is the only breadwinner. Even with his job at the tire store, Enrique is an economic drain.

Worse, he is sullying the only thing her family owns: its good name.

They speak bitter words that both, along with Enrique’s Grandmother Agueda, will recall months later. “Where are you coming from, you old bum?” Ana Lucia asks as Enrique walks in the door. “Coming home for food, huh?”

“Be quiet!” he says. “I’m not asking anything of you.”

“You are a lazy bum! A drug addict! No one wants you here.” All the neighbors can hear. “This isn’t your house. Go to your mother!”

Over and over, in a low voice, Enrique says, half pleading, “You better be quiet.”

Finally, he snaps. He kicks Ana Lucia twice, squarely in the buttocks.

She shrieks.

His grandmother runs out of the house. She grabs a stick and threatens to club him if he touches Ana Lucia again. Now even his grandmother wishes he would go to the United States. He is hurting the family--and himself. She says, “He’ll be better off there.”

::

Goodbye

Maria Isabel, Enrique’s girlfriend, finds him sitting on a rock at a street corner, weeping, rejected again. She tries to comfort him. He is high on glue. He tells her he sees a wall of fire that is killing his mother. “Por que me dejo?” he cries out. “Why did she leave me?”

He feels shame for what he has done to his family and what he is doing to Maria Isabel, who might be pregnant. He fears he will end up on the streets or dead. Only his mother can help him. She is his salvation. “If you had known my mom, you would know she’s a good person,” he says to his friend Jose. “I love her.’’

Enrique has to find her. He sells the few things he owns: his bed, a gift from his mother; his leather jacket, a gift from his dead uncle; his rustic armoire, where he hangs his clothes.

He crosses town to say goodbye to Grandmother Maria. Trudging up the hill to her house, he encounters his father. “I’m leaving,” he says. “I’m going to make it to the U.S.” He asks him for money.

His father gives him enough for a soda and wishes him luck.

“Grandma, I’m leaving,” Enrique says. “I’m going to find my mom.”

Don’t go, she pleads. She promises to build him a one-room house in the corner of her cramped lot.

But he has made up his mind.

She gives him 100 lempiras, about $7--all the money she has.

“I’m leaving already, Sis,” he tells Belky the next morning.

She feels her stomach tighten. They have lived most of their lives apart, but he is the only one who understands her loneliness. Quietly she fixes a special meal: tortillas, a pork cutlet, rice, fried beans with a sprinkling of cheese.

“Don’t leave,” she says, tears welling in her eyes.

“I have to.”

It is hard for him too. Every time he has talked to his mother, she has warned him not to come--it’s too dangerous. But if somehow he gets to the U.S. border, he will call her. Being so close, she’ll have to welcome him. “If I call her from there,” he says to Jose, “how can she not accept me?”

He makes himself one promise: “I’m going to reach the United States, even if it takes one year.”

Only after a year passes will he give up, turn on his heel and go back.

Quietly, Enrique, the slight kid with a boyish grin, fond of kites, spaghetti, soccer and break dancing, who likes to play in the mud and watch Mickey Mouse cartoons with his 4-year-old cousin, packs up his belongings: corduroy pants, a T-shirt, a cap, gloves, a toothbrush and toothpaste.

For a long moment, he looks at a picture of his mother, but he does not take it. He might lose it.

He writes her telephone number on a scrap of paper. Just in case, he also scrawls it in ink on the inside waistband of his pants.

He has $57 in his pocket.

On March 2, 2000, he goes to his Grandmother Agueda’s house. He stands on the same porch that his mother disappeared from 11 years before.

He hugs Maria Isabel and Aunt Rosa Amalia. Then he steps off.

Next: Chapter Two: Badly Beaten, a Boy Seeks Mercy in a Rail-Side Town

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.