Enrique’s Journey | Chapter Four: Inspired by Faith, the Poor Rush Forth to Offer Food

From the top of his rolling freight car, Enrique sees a figure of Christ.

In the fields of Veracruz state, among farmers and their donkeys piled with sugar cane, rises a mountain. It towers over the train he is riding. At the summit stands a statue of Jesus. It is 60 feet tall, dressed in white, with a pink tunic.

The statue stretches out both arms. They reach toward Enrique and his fellow wayfarers on top of their rolling freight cars.

Some stare silently. Others whisper a prayer.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Thursday, Oct. 10, 2002: Enrique’s Journey -- Chapter 4 of the six-part series, published Friday in Section A, described Teotihuacan in Mexico as an Aztec metropolis. The Aztecs adopted the site as a ceremonial ground and gave it its modern name, but it originated and peaked as a metropolis during the pre-Aztec period.

------------

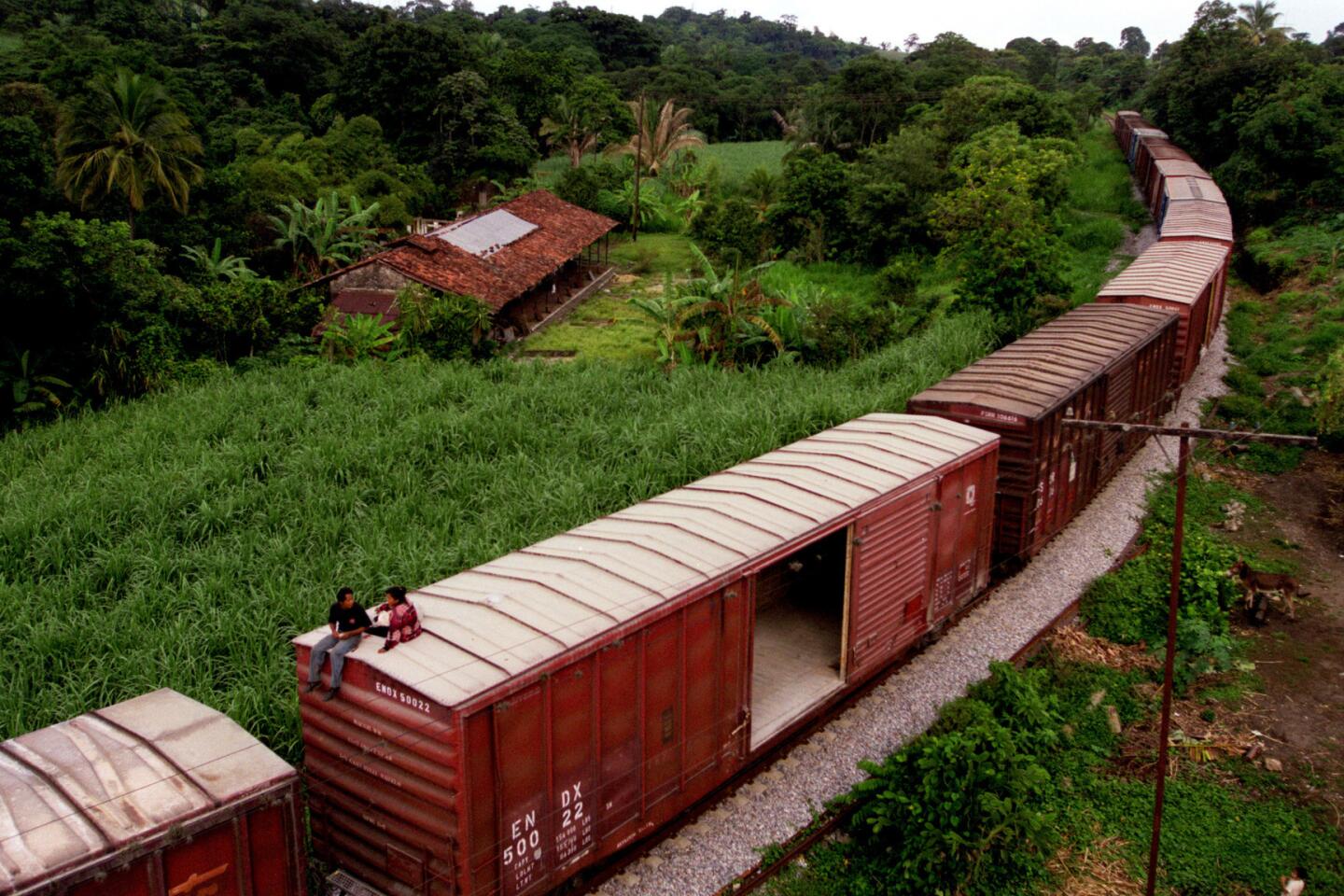

It is early April 2000, and they have made it nearly a third of the way up the length of Mexico, a handful of immigrants, riding on boxcars, tank cars and hoppers. Enrique is 17. He is one of an estimated 48,000 Central American and Mexican children who go to the United States alone every year. Many are searching for their mothers, who have left for El Norte to find work and never come back.

Many credit religious faith for their progress. They pray on top of the train cars. At stops, they kneel along the tracks, asking God for help and guidance. They ask him to keep them alive until they reach El Norte. They ask him to protect them against bandits, who rob and beat them; police, who shake them down; and la migra, the Mexican immigration authorities, who deport them.

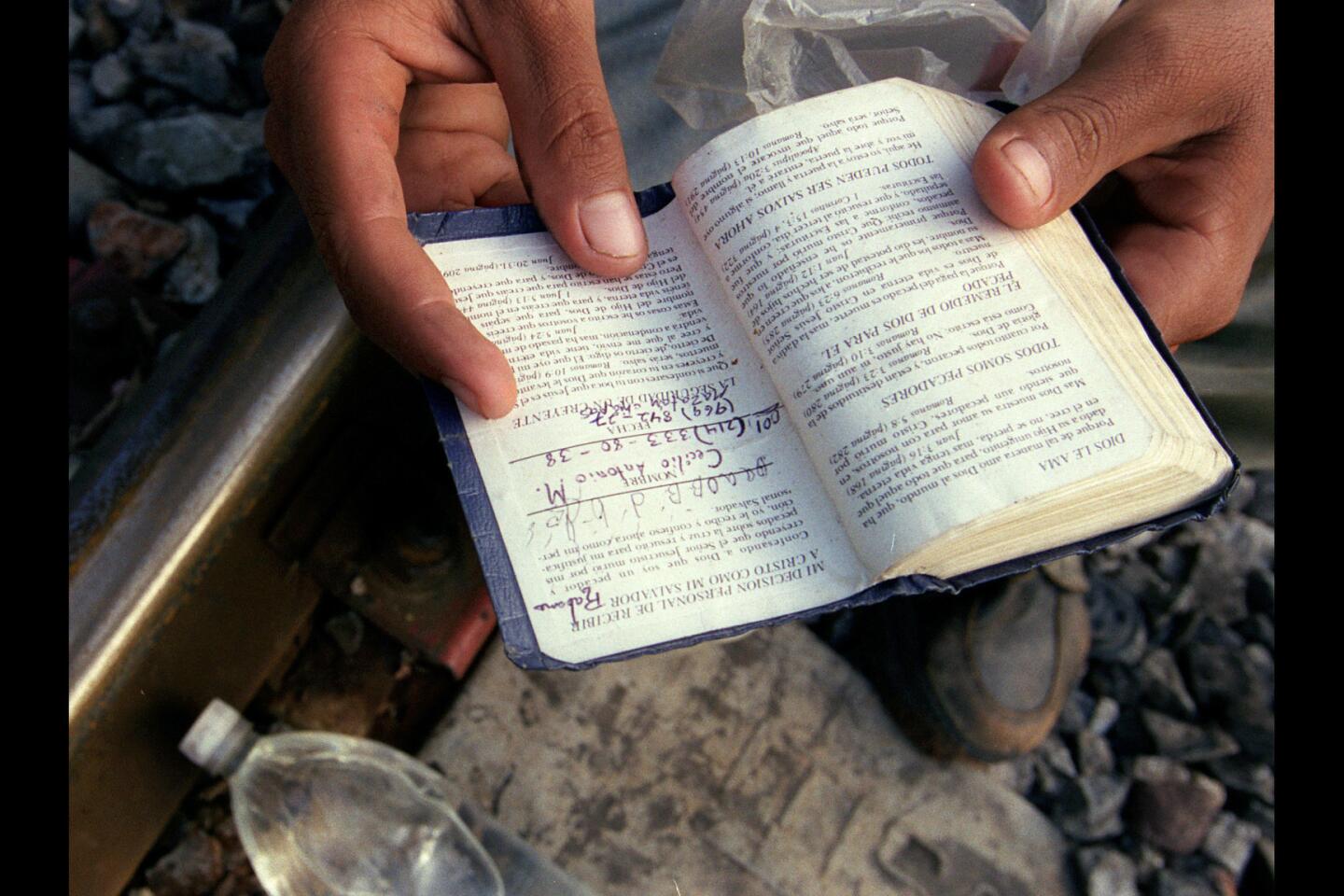

Many carry small Bibles, wrapped in plastic bags to keep them dry. On the pages, in the margins, they scrawl the names and addresses of the people who help them. The police often check the bindings for money to steal, the migrants say, but usually hand the Bibles back.

Some pages are particularly worn. The one that offers the 23rd Psalm, for instance: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.”

Or the 91st Psalm: “There shall no evil befall thee, neither shall any plague come nigh thy dwelling. For he shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways.”

Some migrants rely on a special prayer, “La Oracion a las Tres Divinas Personas”--a prayer to the Holy Trinity. It has seven sentences--short enough to recite in a moment of danger. If they rush the words, God will not mind.

That night, Enrique climbs to the top of a boxcar. In the starlight, he sees a man on his knees, bending over his Bible, praying.

Enrique climbs back down.

He does not turn to God for help. With all the sins he has committed, he thinks he has no right to ask God for anything.

::

Small bundles

What he receives are gifts.

Enrique expects the worst. Riding trains through the state of Chiapas, which immigrants call “the beast,” has taught him that any upraised hand might hurl a stone. But here in the states of Oaxaca and Veracruz, he discovers that people are friendly. “It’s just the way we are,” says Jorge Zarif Zetuna Curioca, a legislator from Ixtepec.

Perhaps not everyone is that way, but there is a widespread generosity of spirit. Many residents say it is rooted in the Zapotec and Mixtec indigenous cultures. Besides, some say, giving is a good way to protest Mexico’s policies against illegal immigration.

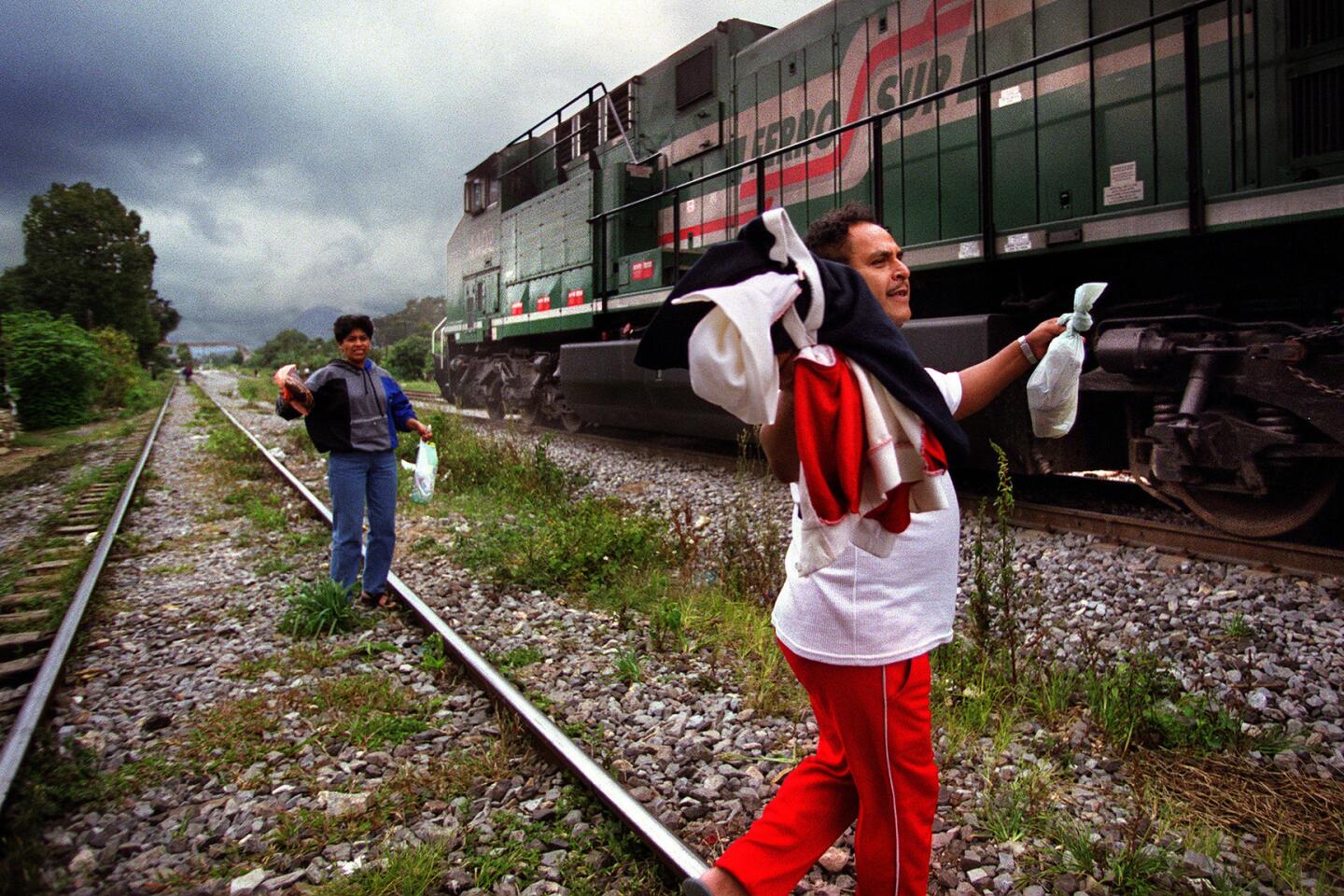

Not long after seeing the statue of Jesus, Enrique is alone on a hopper. Night has fallen, and as the train passes through a tiny town, it blows its soulful horn. He looks over the side. More than a dozen people, mostly women and children, are rushing out of their houses along the tracks, clutching small bundles.

Some of the migrants grow afraid. Will these people throw rocks? They lie low on top of the train. Enrique sees a woman and a boy run up alongside his hopper.

“Orale, chavo! Here, boy!” they shout.

They toss up a roll of crackers. It is the first gift.

Enrique reaches out. He grabs with one hand, but holds tightly to the hopper with the other. The roll of crackers flies several feet away, bounces off the car and thumps to the ground.

Now women and children on both sides of the tracks are throwing bundles to the immigrants on the tops of the cars. They run quickly and aim carefully, mostly in silence, trying hard not to miss.

“Alli va uno! There’s one!”

Enrique looks down. There are the same woman and boy. They are heaving a blue plastic bag. This time the bundle lands squarely in his arms.

“Gracias! Adios!” he says into the darkness. He isn’t sure the strangers, who pass by in a flash, even heard him.

He opens the bag. Inside are half a dozen rolls of bread.

Enrique is stunned by the generosity. In many places where the train slows in Veracruz, at a curve or to pass through a village, people give. Sometimes 20 or 30 people stream out of their homes along the rails and toward the train. They smile, then shout and throw food.

The towns of Encinar, Fortin de las Flores, Cuichapa and Presidio are particularly known for their kindness. These are unlikely places for people to be giving food to strangers. A World Bank study in 2000 found that 42.5% of Mexico’s 100 million people live on $2 or less a day. Here, in rural areas, 30% of children 5 and younger eat so little that their growth is stunted, and the people who live in humble houses along the rails are often the poorest.

Families throw sweaters, tortillas, bread and plastic bottles filled with lemonade. A baker, his hands coated with flour, throws his extra loaves. A seamstress throws bags filled with sandwiches. A teenager throws bananas. A store owner throws animal crackers, day-old pastries and half-liter bottles of water.

A young man, Leovardo Santiago Flores, throws oranges in November, when they are plentiful, and watermelons and pineapples in July. A stooped woman, Maria Luisa Mora Martin, more than 100 years old, who was reduced to eating the bark of her plantain tree during the Mexican Revolution, forces her knotted hands to fill bags with tortillas, beans and salsa so her daughter, Soledad Vasquez, 70, can run down a rocky slope and heave them onto a train.

“If I have one tortilla, I give half away,” one of the food throwers says. “I know God will bring me more.”

Another: “I don’t like to feel that I have eaten and they haven’t.”

Still others: “When you see these people, it moves you. It moves you. Can you imagine how far they’ve come?”

“God says, when I saw you naked, I clothed you. When I saw you hungry, I gave you food. That is what God teaches.”

“It feels good to give something that they need so badly.”

“I figure when I die, I can’t take anything with me. So why not give?”

“What if someday something bad happens to us? Maybe someone will extend a hand to us.”

::

New cargo

Enrique is hungry, but he fears that the half-dozen rolls from the food throwers might be all there is to his good fortune, so he stashes them for later.

In little more than an hour, the train nears a town: Cordoba.

The cargo is beginning to change. It is valuable and more easily damaged--Volkswagens, Fords and Chryslers. Security guards check the freight cars, catch every rider they can and hand them over to authorities. More important, says Cuauhtemoc Gonzalez Flores, an official of the Transportacion Ferroviaria Mexicana railroad, if a migrant falls and is injured or killed, it costs $8 a minute to stop the train, often for hours, until investigators arrive.

A sewage stream appears by the tracks. Cordoba is getting close. The immigrants finish their water, because it is hard to run fast holding bottles. They tie sweaters or extra shirts around their waists. Enrique grabs his bag of bread. About 10 p.m., he smells a familiar cue: a coffee-roasting factory next to the red brick station. As the train slows, he leaps and flees.

He sits on a sidewalk one block north of the station. Two police officers approach.

His odds are better if he does not bolt. He tucks his bread into a crevice. He swallows his fright and tries to look unconcerned.

The officers, in navy blue uniforms, walk straight up to him.

He does not move, even flinch. Cops can sense fear. They can tell if someone is illegal. You have to be calm, he says to himself. You can’t look afraid or hide. You have to look right at them.

Unlike food throwers, the police do not bear gifts. They pull out pistols.

“If you run, I’ll shoot you,” one says, aiming at Enrique’s chest.

They take him and two younger boys, sitting nearby, to a cavernous railroad shed, where seven other officers are holding 20 migrants.

It is a full-scale sweep.

They line up the immigrants against a wall. “Take everything out of your pockets.”

Only a bribe, Enrique knows, will keep him from being deported back to Central America. He has 30 pesos, about $3, that he earned lifting rocks and sweeping near the tracks in Tierra Blanca. He prays it will be enough.

One officer pats him down and says to empty his pockets.

Enrique drops his belt, a Raiders cap and the 30 pesos. He glances at his fellow migrants. Each is standing behind a little pile of belongings.

“Salganse! Vayanse, ya! Get out! Leave!”

He will not be deported. But he pauses. He screws up his courage. “Can I get my things back, my money?”

“What money?” the officer replies. “Forget about it, unless you want to have your trip stop here.”

Enrique turns his back and walks away.

Even in Veracruz, where strangers can be so kind, the authorities cannot be trusted. The chief of state police in nearby Fortin de las Flores will not comment on the incident.

Exhausted, Enrique retrieves his bag of bread, climbs onto a flatbed truck and sleeps. At dawn, he hears a train. He trots alongside a freight car and clambers aboard, holding his bread.

::

The mountains

The tracks, smoother now, begin to climb. It grows cooler. The train passes 60-foot stalks of bamboo. It rolls through putrid white smoke from a Kimberly-Clark factory that turns sugar cane pulp into Kleenex and toilet paper.

In Orizaba, the train changes crews. Enrique asks a man standing near the tracks, “Can you give me one peso to buy some food?” The man inquires about his scars. They are from a beating little more than a week ago on top of a train. He gives Enrique 15 pesos, about $1.50.

Enrique runs to buy soda and cheese to go with his bread. He looks north and sees snow-covered Pico de Orizaba, the highest summit in Mexico. Now it will turn icy cold, especially at night, much different from the steamy lowlands. Enrique begs two sweaters. Before the train pulls out, he runs from car to car, looking into the hollows at the ends of the hoppers, where riders occasionally discard clothing. In one, he finds a blanket.

As the train starts, Enrique shares his cheese, soda and rolls with two other boys, also headed for the United States. One is 13. The other is 17. Silently, Enrique thanks the food throwers again for the bread.

He relishes the camaraderie: how riders take care of one another, pass along what they know, divide what they have. Camaraderie often means survival. “I could get to the north faster alone,” he figures, “but I might not make it.”

The mountains close in. Enrique invites the two boys to share his blanket. Together they will be warmer. The three jam themselves between a grate and an opening on top of a hopper. Enrique stuffs rags under his head for a pillow. The car sways, and its wheels click-clack quietly. They sleep.

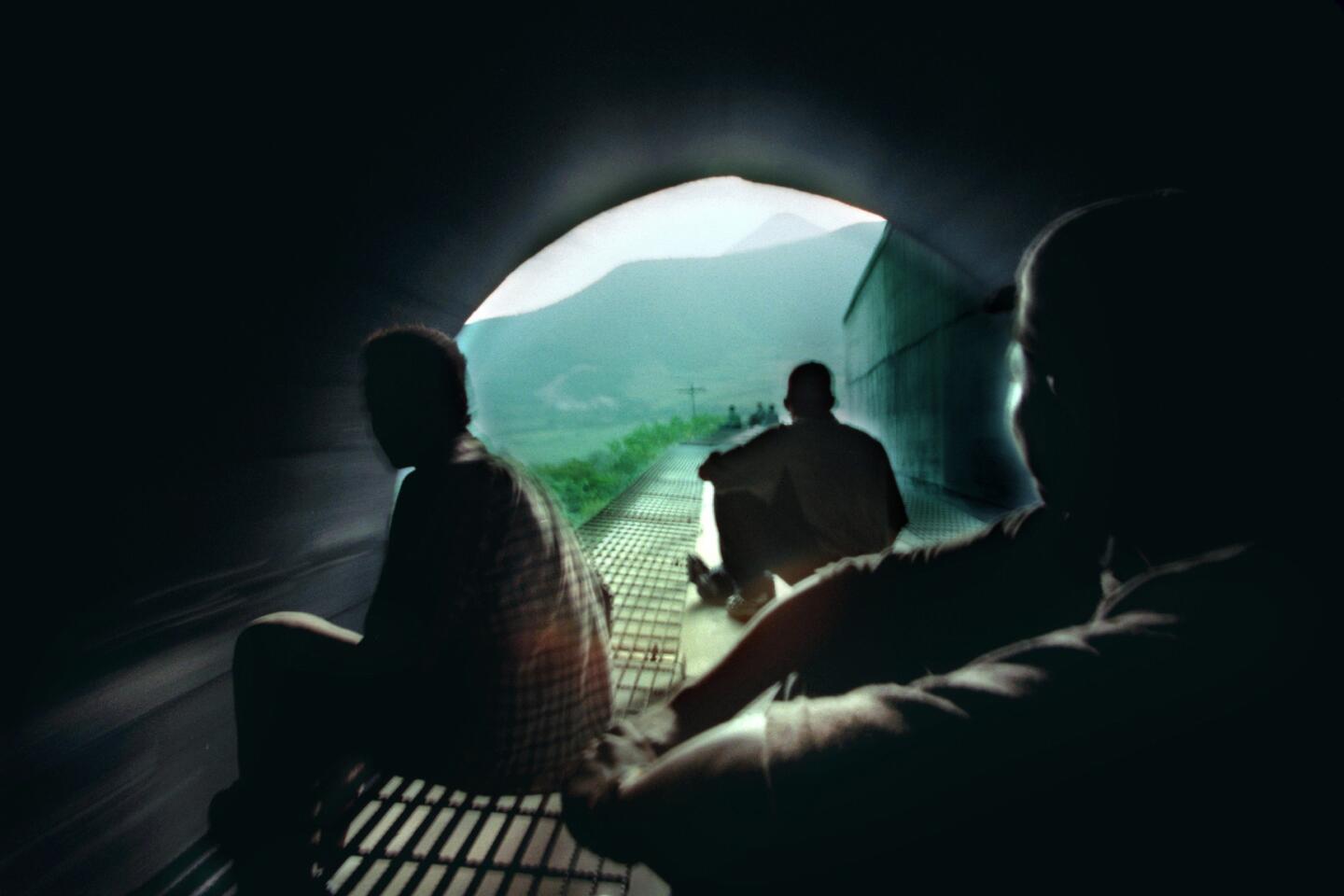

The train enters a tunnel, the first of 32 in the Cumbres de Acultzingo, or the Peaks of Acultzingo. Outside is bright sun. Inside is darkness so black that riders cannot see their hands. They shout, “Ay! Ay! Ay! Ay! Ay!” and listen for the echo. Enrique and his friends sleep on. Back in the daylight, the train hugs a hillside. Below, a valley is filled with fields of corn, radishes and lettuce, each a different hue of green.

El Mexicano is the longest tunnel. For eight minutes, the train vanishes inside. Black diesel smoke hugs the tops of the cars. It burns the lungs and stings the eyes. Enrique’s eyes are closed, but his face and arms turn gray. His nose runs black soot. Engineers fear El Mexicano. If a locomotive overheats, they must stop. Riders spring for the arched exits, gasping for clean air.

Back outside, ice forms on the cars. Riders ache and shiver. Their lips crack, and their eyes grow dull. They hug themselves. They pull their shirts over their mouths to warm themselves with their breath. When the train slows, they jog alongside to ward off the cold. As night falls, some of the older immigrants drink whiskey. Too much and they tumble off. Others gather old clothing and trash and build fires on the ledges over the wheels of the hoppers. Some stand in the warm plumes of diesel smoke.

At dawn, the tracks straighten and level out. At 1 1/2 miles above sea level, the train accelerates to 35 mph. Enrique awakens. He sees cultivated cactus on both sides. Directly in front rise two huge pyramids, the Aztec metropolis of Teotihuacan.

Then he sees switches and semaphores. Housing developments. A billboard for Paradise Spa. A sewage ditch. Taxis.

The train slows for the station at Lecheria. Enrique gets ready to run.

He is in Mexico City.

::

Suspicion

The Veracruz hospitality has vanished.

One woman wrinkles her nose when she talks about migrants. She is hesitant to slide the deadbolt on the metal door of her tall stucco fence. “I’m afraid of them. They talk funny. They are dirty.”

Enrique starts knocking on doors. He begs for food. In Mexico City, where crime is rampant, people are often hostile. “We don’t have anything,” they say at house after house, usually through locked doors.

Finally, at one house, another gift: A woman offers him tortillas, beans and lemonade.

Now he must hide from the state police, who guard the depot at Lecheria, a gritty industrial neighborhood on the northwestern outskirts of Mexico City. He crawls into a 3-foot-wide concrete culvert.

At 10:30 p.m., a northbound train arrives. From Mexico City onward, the rail system is more modern, and trains run so fast that few immigrants ride on top. Enrique and his two friends pick an open boxcar. If they are caught inside, it will be hard to escape, but they count on the scarcity of migra checkpoints in northern Mexico. The boys load cardboard to lie on and stay clean.

Enrique notices a blanket on a nearby hopper. He climbs a ladder to get it and hears a loud buzz from overhead. Live wires carry electricity above the trains for 143 miles north. Once used for locomotives that no longer operate, the wires still carry 25,000 volts to prevent vandalism. Signs warn: “Danger--High Voltage.” But many of the migrants cannot read.

They do not even need to touch the lines to be killed. The electricity arcs up to 20 inches. Only 36 inches separate the wires from the tallest freight cars, the auto carriers. In railroad offices in Mexico City, computers plot train routes with blue and green lines, and at least once every six months the screens flicker, then black out. An immigrant has crawled on top of a car, been hit by electricity and short-circuited the system. When the computers reboot, the screens flash red where it happened.

Enrique climbs the hopper car. Carefully, he snatches a corner of the blanket and yanks it down. Then he scrambles back to his boxcar and settles into a bed that he and his friends have fashioned out of straw they found inside.

The boys share a bottle of water and one of juice. They plow through a heavy fog, and Enrique sleeps soundly--too soundly.

He does not sense when police stop their train in the middle of the central Mexican desert. Officers dressed in black find the boys curled under their blanket in the straw. They take them to their jefe, who is cooking a pot of stew over a campfire. He pats them down to check for drugs. Then, instead of arresting them, he gives all three tortillas and water--and toothpaste to clean up.

Enrique is astonished. The jefe lets them re-board the boxcar and tells them to get off the train before San Luis Potosi, where 64 railroad security officers guard the station. At midmorning, Enrique sees two flashing red antennas. The boys jump off the train half a mile south of town.

Until now, Enrique has opted to keep moving. But here the countryside is too desolate to live off the land, and begging is too chancy. He needs to work if he is going to survive. Besides, he does not want to reach the border penniless. He has heard that U.S. ranchers shoot immigrants who come to beg.

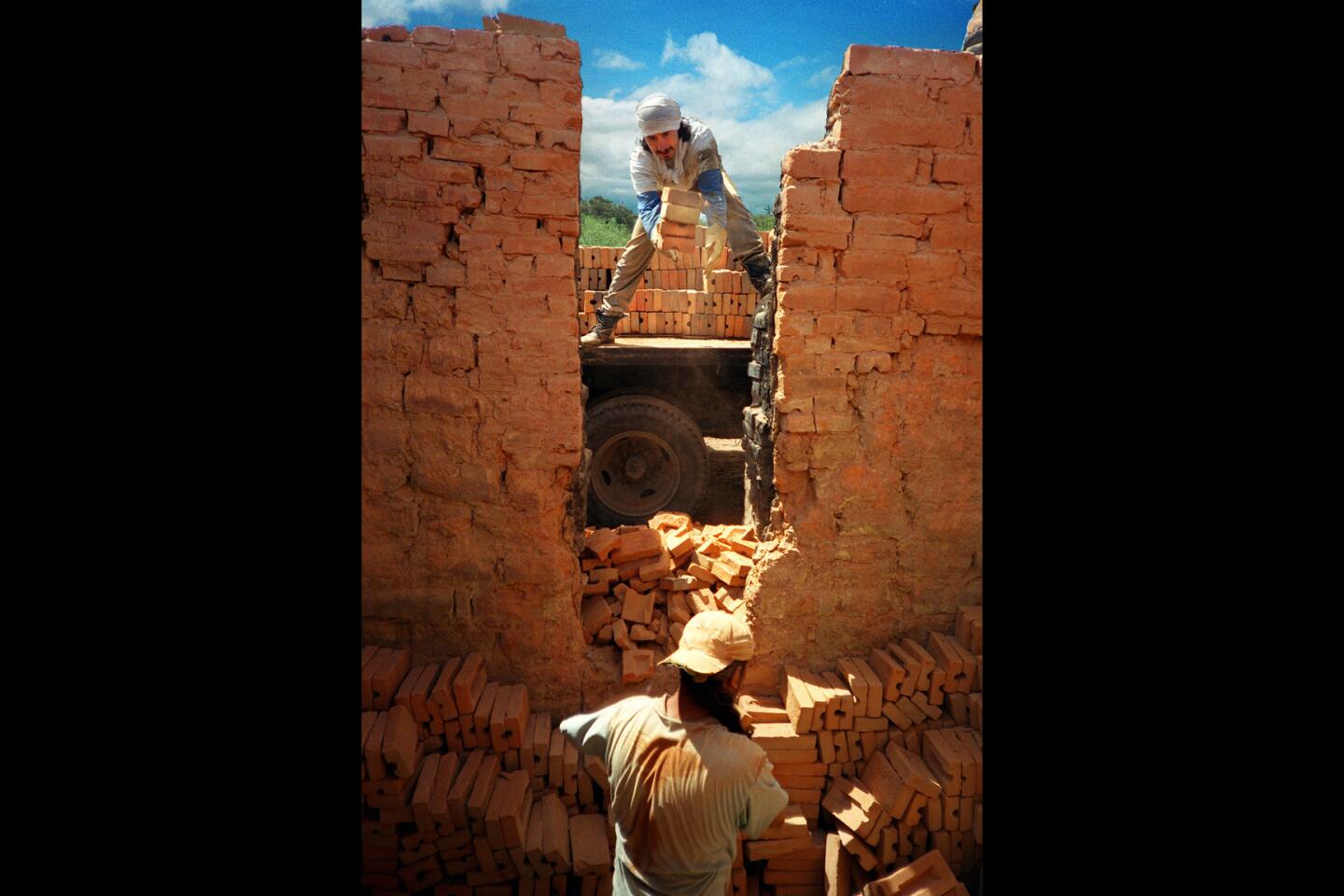

He trudges up a hill to the small home of a brick maker. Politely, Enrique asks for food. The brick maker offers yet another kindness: If Enrique will work, he will get both food and a place to sleep.

Happily, Enrique accepts.

Some migrants say Mexicans exploit illegals for a fraction of the going wage, which is 50 pesos, or about $5, a day. But the brick maker does better than that: 80 pesos. And he gives Enrique shoes and clothing.

For a day and a half, Enrique works at the brickyard, one of 300 that straddle the tracks on the northern edge of San Luis Potosi. Workers pour clay, water and dried cow manure into large pits. They roll up their pants and stomp on the sloppy concoction, as if pressing grapes to make wine. When the slop becomes a firm brown paste, they slap it into wooden molds. Then they empty the molds on flat ground and let the bricks dry.

The bricks are stacked into pyramids inside ovens as big as rooms. Under the ovens, the fires are stoked with sawdust. Each batch of bricks bakes for 15 hours, sending clouds of black smoke into the sky.

Enrique’s job is to shovel the clay. At night, he sleeps in a shed on a dirt floor he shares with one of his friends from the train.

“I have to get to the border,” Enrique tells him.

Should he take another train? Freight cars have brought him 990 miles from Tapachula near Guatemala. Is he pushing his luck?

His employer says he should ride a Volkswagen van called a combi through a checkpoint about 40 minutes north of town. The authorities won’t stop a combi, the brick maker says. Then he should take a bus to Matehuala, and he might be able to get a ride on a truck all the way to Nuevo Laredo on the Rio Grande.

::

The trucker

Enrique collects his pay, 120 pesos. He spends a few on a toothbrush.

He hails a combi. It breezes through the checkpoint. He pays 83 pesos to board a bus to Matehuala. Outside the bus station, he sees a kindly looking man.

“Can you help me?” Enrique asks.

The man gives him a place to sleep. The next morning, Enrique walks to a truck stop.

“I don’t have any money,” he tells every driver he sees. “Can you give me a ride however far north you are going?”

One after another, they turn him down. If they said yes, police might accuse them of smuggling. Drivers say it is enough to worry about officers planting drugs on their trucks and demanding bribes. Moreover, some of the truckers fear that immigrants might assault them.

Finally, at 10 a.m., one driver takes the risk.

Enrique pulls himself up into the cab of an 18-wheeler hauling beer.

“Where are you from?” the driver asks.

Honduras.

“Where are you going?” The driver has seen boys like Enrique before. “Do you have a mom or dad in the United States?”

Enrique tells him about his mother.

A sign at Los Pocitos says, “Checkpoint in 100 Meters.” The truck idles in line. Then it inches forward. Judicial police officers ask the driver what he is carrying. They want his papers. They peer at Enrique.

The driver is ready: My assistant.

But the officers do not ask.

A few feet farther on, soldiers stop each vehicle to search for drugs and guns. Two fresh-faced recruits wave them through.

Oblivious to chatter on the trucker’s two-way radio, Enrique falls asleep. The driver clears two more checkpoints. As he nears the Rio Grande, he stops to eat. He buys Enrique a plate of eggs and refried beans and a soda, another gift.

Riding a truck, Enrique figures, is a dream.

Sixteen miles before the border, he sees a sign: “Reduce Your Speed. Nuevo Laredo Customs.”

Don’t worry, the driver says, la migra check only the buses.

A sign says, “Bienvenidos a Nuevo Laredo.” Welcome to Nuevo Laredo.

The driver drops him off. With 30 pesos he has left, he takes a bus that winds into the city.

He has one more piece of good fortune. At the Plaza Hidalgo, in the heart of Nuevo Laredo, Enrique sees a man from Honduras whom he has met on a train. The man takes him to an encampment along the Rio Grande. Enrique likes it. He decides to stay until he can cross.

That night, as the sun sets, Enrique stares across the Rio Grande and gazes at the United States. It looms as a mystery.

Somewhere over there lives his mother. She has become a mystery too. He was so young when she left that he can barely remember what she looks like: curly hair; eyes like chocolate. Her voice is a distant sound on the phone.

Enrique has spent 47 days bent on nothing but surviving. Now, as he thinks about her, he is overwhelmed.

Next: Chapter Five: A Milky Green River Between Him and His Dream

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.