El Niño temperatures in Pacific Ocean break 25-year record: ‘It’s coming’

Low clouds drift over the Los Angeles Basin and downtown as light rain and cooler temperatures prevail on Oct. 18.

Temperatures in a key location of the Pacific Ocean are now far hotter than they ever were in the record 1997 El Niño.

Some scientists say the readings show that this year’s El Niño could be among the most powerful on record -- and even topple the 1997 El Niño from its pedestal.

“This thing is still growing and it’s definitely warmer than it was in 1997,” said Bill Patzert, climatologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. As far as the temperature readings go, “it’s now bypassed the previous champ of the modern satellite era -- the 1997 El Niño has just been toppled by 2015.”

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at Stanford University, called the temperature reading significant. It is the highest such weekly temperature above the average in 25 years of modern record keeping in this key region of the Pacific Ocean west of Peru.

“This is a very impressive number,” Swain said, adding that data suggest that this El Niño is still warming up. “It does look like it’s possible that there’s still additional warming” to come.

“We’re definitely in the top tier of El Niño events,” Swain said.

Temperatures in this key area of the Pacific Ocean rose to 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit above average for the week of Nov. 11. That exceeds the highest comparable reading for the most powerful El Niño on record, when temperatures rose 5 degrees Fahrenheit above the average the week of Thanksgiving in 1997.

The 5.4 degree Fahrenheit recording above the average temperature is the highest such number since 1990 in this area of the Pacific Ocean, according to the National Weather Service.

El Niño is a weather phenomenon involving a section of the Pacific Ocean west of Peru that warms up, causing alterations in the atmosphere that can cause dramatic changes in weather patterns globally.

For the United States, El Niño can shift the winter track of storms that normally keeps the jungles of southern Mexico and Central America wet and moves them over California and the southern United States. The northern United States, like the Midwest and Northeast, typically see milder winters during El Niño.

The National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center has already forecast a higher chance of a wet winter for almost all of California and the southern United States.

But the center’s deputy director, Mike Halpert, cautioned against reading too much into the record-breaking weekly temperature data.

El Niño has so far been underperforming in other respects involving changes in the atmosphere important to the winter climate forecast for California, he said.

One example: tropical rainfall has not extended from the International Date Line and eastward, approaching South America, as it did by this time in 1997.

“In 1997, that pattern has largely established itself,” Halpert said, but that pattern so far is “significantly weaker” than it was back then.

Still, Halpert said, “it’s not too late for things to develop.”

Patzert, the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory climatologist, said the increase in ocean temperatures west of Peru was a result of a dramatic weakening of the normal east-to-west trade winds in the Pacific Ocean that were observed in October around the International Date Line.

That allowed the warm, tropical ocean waters in the western Pacific Ocean to surge to the Americas, leading to this increase in ocean temperatures observed last week.

The 1997 El Niño has been considered the strongest such event since the 1950s. The modern era of El Niño tracking came after the 1982-83 event, which came as a surprise and is considered the second strongest on record.

The 1997 El Niño was considered so strong and that scientists have been impressed that this El Niño could top that event.

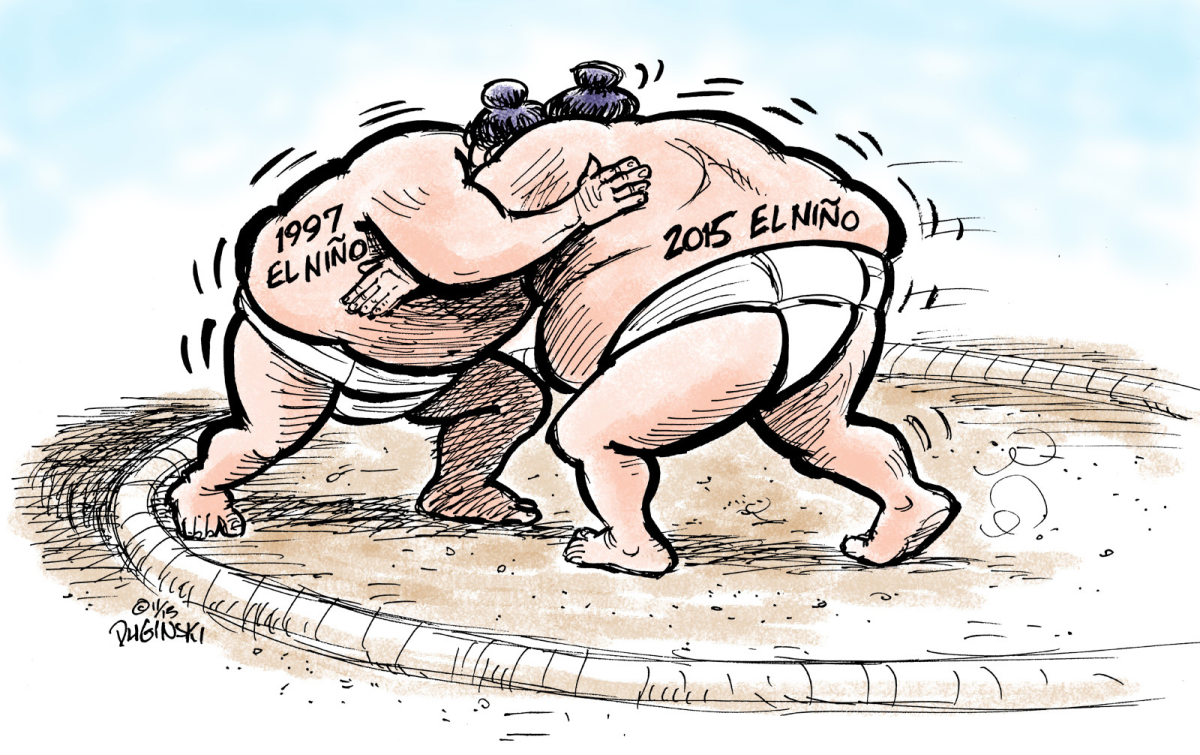

Patzert likened it to the shocking defeat of the previously unbeaten Ultimate Fighting Championship champion Ronda Rousey over the weekend by Holly Holm. Or, he added, like the dethroning of a grand champion in sumo wrestling.

This El Niño “just flipped the 1997-98 El Niño out of the ring,” Patzert said.

El Niño is already being blamed for drought and wildfires in Indonesia, and the United Nations is warning about millions at risk from hunger in eastern and southern Africa and Central America from drought.

El Niño is believed to have played a role in the storms this spring that caused floods and ended droughts in Colorado, Texas and Oklahoma. It’s also a factor in the fewer number of hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean while there has been more of them in the eastern Pacific.

The unusually active hurricane season has already had impacts on California. Remnants of a summertime hurricane caused so much rain to pour down in Riverside County that an Interstate 10 bridge collapsed. It dumped so much hail near Lake Tahoe that snowplows were called to clear Interstate 80. Last month, an eastern Pacific hurricane, Patricia, became the strongest such cyclone recorded in the Western Hemisphere before it slammed into Mexico.

“It’s not as if we’re waiting for El Niño to actually manifest itself -- it has in many ways already,” Patzert said. “There is no doubt: It’s coming.”

The big question is whether the above-average ocean temperatures will cause the mountains of Northern California -- a critical source for the state’s largest reservoirs -- to get rain instead of snow. Too much rain in those mountains would not be good for the state; snow is better because it can melt slowly in the spring and summer, gradually refilling reservoirs at a gentle pace. But precipitation coming down as rain there can force dam managers to flush out water to sea to keep reservoirs from overflowing dams.

“The really high elevations in the Sierra Nevada will do well,” Swain said, but it’s unknown whether the more important mid-level elevations will get rain or snow.

Scientists say they expect El Niño rains to be concentrated in the months of January, February and March.

“At some point, during December, we’ll transition to a much more active pattern” for storms, Swain said. “And by the end of December, and certainly by January, February and March, we’ll see above average precipitation, potentially well-above average.”

“El Niño is going to be a dominant factor this winter,” Swain said.

El Niño is also expected to provide once-in-a-generation waves on beaches not seen since the 1997-98 event, Patzert said, affecting the entire west coast of North America, “from British Columbia all the way down to Costa Rica.”

“The best surfing waves often precede the storms,” Patzert said. “If you have a great day of surfing -- Malibu or Mavericks or someplace -- during an El Niño, then in the next day or two you can expect a big storm.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.