Analysis: The anti-Trump: Tom Bradley, a quiet giant who bridged divides

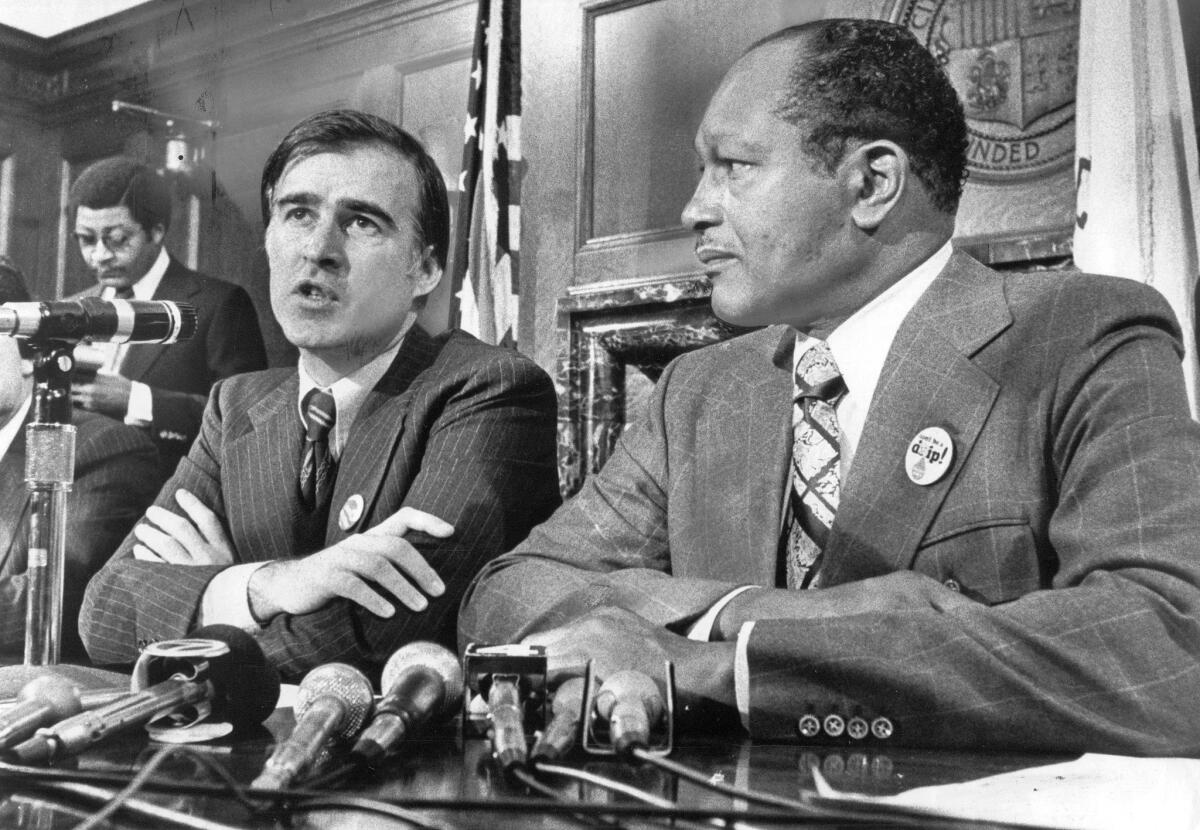

Gov. Jerry Brown and Mayor Tom Bradley discuss water issues and the drought in the mayor’s City Hall conference room in 1977.

In this summer of Trump, it can be hard to figure out when American politics reached the high water mark in bloviating.

Was it when Donald Trump sneered at his presidential competitors as “losers”?

Was it when the Republican declared that the United States has “stupid leadership” — apparently, bipartisan?

Was it when he suggested that Fox broadcaster Megyn Kelly treated him poorly at a recent debate because she was menstruating?

Maybe we haven’t even hit the mark yet. There’s plenty of time to go.

Yet if the presidential campaign already serves as a near-constant reminder of why people hate politics and dislike the people who practice it, an antidote may arrive for some in the form of a new documentary called “Bridging the Divide.” Airing Tuesday at 8 p.m. on PBS SoCal, and across the nation early next year, it shines new focus on former Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, who died in 1998, five years after he left office.

In place of the rat-a-tat insults so common in the current presidential campaign, there is Bradley, the dignified 20-year mayor, enduring slight after slight as he works for a Los Angeles Police Department that had little use for his kind. There is Bradley, upending his Democratic Party’s reputation for fiscal laxity, working with others to protect the city’s budget. There is Bradley throwing open City Hall, literally and figuratively, to blacks and Latinos and Asians and women, a City Hall that to that point had been largely the province of white men.

There is Bradley, with his peers, working not on bitter gibes but on the big stuff — the growth of a city, the poverty of many of its citizens, the grandeur of a wildly successful Olympic Games, fiery violence in the form of a race-based riot.

It is a lovingly rendered portrait; indeed, it omits mention of the accusations toward the end of Bradley’s time in office of financial mistakes that tarnished his reputation. But for people of all political measures, it is also a reminder of the dedication and deliberation that it can take to be a public servant of long tenure.

The particularly fraught complications of being an African American politician were most acutely on display. Bradley was, in his younger years, something of a rebel, in the sense that he battled against the prevailing establishment of the time. Just becoming an LAPD officer in a department led by William Parker, whose refusal to allow Bradley to rise in leadership led indirectly to Bradley’s entrance into politics, was somehow revolutionary. As was buying a home, undercover, in a largely white area of the city.

Attitudinally, none of that surfaced as Bradley sought elected office, for any simmering ire or resentment, however human, would have scotched his ambitions.

“In order for Bradley to have navigated effectively in a white world, much like President Obama, he needed to be non-threatening,” said filmmaker Alison Sotomayor, who spent seven years nurturing the documentary along with partner Lyn Goldfarb. “He survived very well in a world of white men.”

Like Obama, Bradley was far more affable in private than in public, a jazz aficionado with a deep laugh. As politicians grew more publicly confessional, Bradley stood apart, in part because of his personality but also in part because of what he was.

“If you are a tall, medium-to-dark-skinned African American man, you’re going to get a certain reaction, and he learned how to moderate the reaction,” said Christopher Jimenez y West, an assistant professor of history at Pasadena City College, who served as a consultant for the filmmakers.

For Bradley to have achieved five victories in mayoral elections, in a city driven by racial splits and with a minimal black population, “makes the story that much more incredible,” Jimenez y West said.

The film underscored the generational shift in political figures that, arguably, has made modern practitioners a bit less tough and tested when they seek office.

Up-from-the-bootstraps stories are an expected part of a politician’s narrative, but for many of today’s politicians the stories are borrowed: Hillary Rodham Clinton’s story of her mother’s arduous upbringing; Mitt Romney’s tale of his father’s struggles for success as an immigrant from Mexico; Rick Santorum’s evocation of his coal miner grandfather’s gnarled hands, the “hands that dug his path in life.”

In Bradley’s case, all of the drama had happened to him, the grandson of a slave, the son of sharecroppers, a man whose own tenure picking cotton as a child had persuaded him to reach for an educated, ambitious life. It gave him the courage of his convictions, to judge by praise tossed on Bradley after a screening of the film Monday night, organized by Cal State L.A.’s Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Institute for Public Affairs.

“As a person who was willing to stand up to interests of all kinds, I don’t think there was anyone who comes close to that level of excellence as a human being as Tom,” said former county Supervisor and Los Angeles City Councilman Zev Yaroslavsky, who occasionally battled with Bradley and almost ran against him for mayor. Once Bradley gave his word, he “stuck to it,” Yaroslavsky said, citing that as a rare occurrence in politics.

Bradley’s coalition government was based on the example set by longtime U.S. Rep. Edward Roybal, a Latino legend who also changed the face of Los Angeles politics. But Bradley stands alone in being the first non-white mayor, the first to serve so many terms — not possible now given term limits — and perhaps the last to seem like he could have been carved on a local Mt. Rushmore, were there such a thing.

“In the midst of it all he never lost his humanity,” said Jimenez y West. “It’s a legacy I don’t know if anybody can pick up.”

Twitter: @cathleendecker. For more on politics go to www.latimes.com/decker.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.