Conniving by crossover voters is more myth than threat

Loch Ness has its monster. The Pacific Northwest has Bigfoot.

And elections have their own mythic creature, feared though seldom seen, who lurks large in the fevered imaginations of candidates, would-be pundits and some paranoid partisans.

It’s the mischief-making crossover voter.

In the popular telling, masses of cunning Democrats and Republicans stand ready and eager to wade into the opposition’s primary, itching to cast a calculated ballot for the weakest possible candidate, thence to be defeated in November.

That sort of meddling is cited by opponents of so-called open primaries — which allow voters to cast ballots for whomever they please, regardless of party — as a reason to limit participation to those of their political affiliation.

It’s also heard now and then as the reason why a certain candidate lost; last year, after the out-of-nowhere defeat of Rep. Eric Cantor in his Virginia primary, some credited (or blamed) the interference of crossover Democrats, who supposedly targeted the No. 2 House Republican.

All of which is a lot of hooey.

Extensive research in California, a proving ground for various voting permutations over the last two decades, shows that that type of electoral sabotage is just about as prevalent as black-lagoon creatures bidding for a seat on the City Council.

The most recent work grows out of a study of California’s top-two primary, a change intended to bring moderation to Sacramento and the state’s congressional delegation by pitting the leading vote-getters in a November runoff. (In brief, the study said it was too soon to draw definitive conclusions but suggested voters would have to be more engaged and attentive for the change to work as supporters hoped.)

As part of his research, New York University’s Jonathan Nagler focused on California’s 2012 Assembly races and a survey of 2,500 registered voters. He found an exceedingly low rate of crossover balloting: Just 5.5% of Democrats voted for a Republican candidate and 7.6% of Republicans supported a Democrat.

Most of those who voted for a candidate from the other party did so not to undermine the opposition, Nagler found, but because registration was so heavily weighted against their own party it was pointless to support one of their own.

The incidence of “raiding,” as political scientists call the act of meddlesome voting, was so minimal it did not even register.

Those findings support research done after California’s 1998 “blanket primary,” another system that allowed voters to cast ballots without regard to party membership. (The blanket primary was struck down in 2000 by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that it unconstitutionally interfered with the right of parties to control their nominating process. Legal challenges to the two-top primary have so far proved unavailing.)

So why in this age of acute partisanship do so few voters take advantage of a chance to torpedo the opposition?

Nagler offers several reasons, starting with the fact it’s difficult to know exactly how to do so.

California’s open primary doesn’t apply to presidential races. But if it had back in 1980, Democrats might have seen the ideal chance to mess with Republicans.

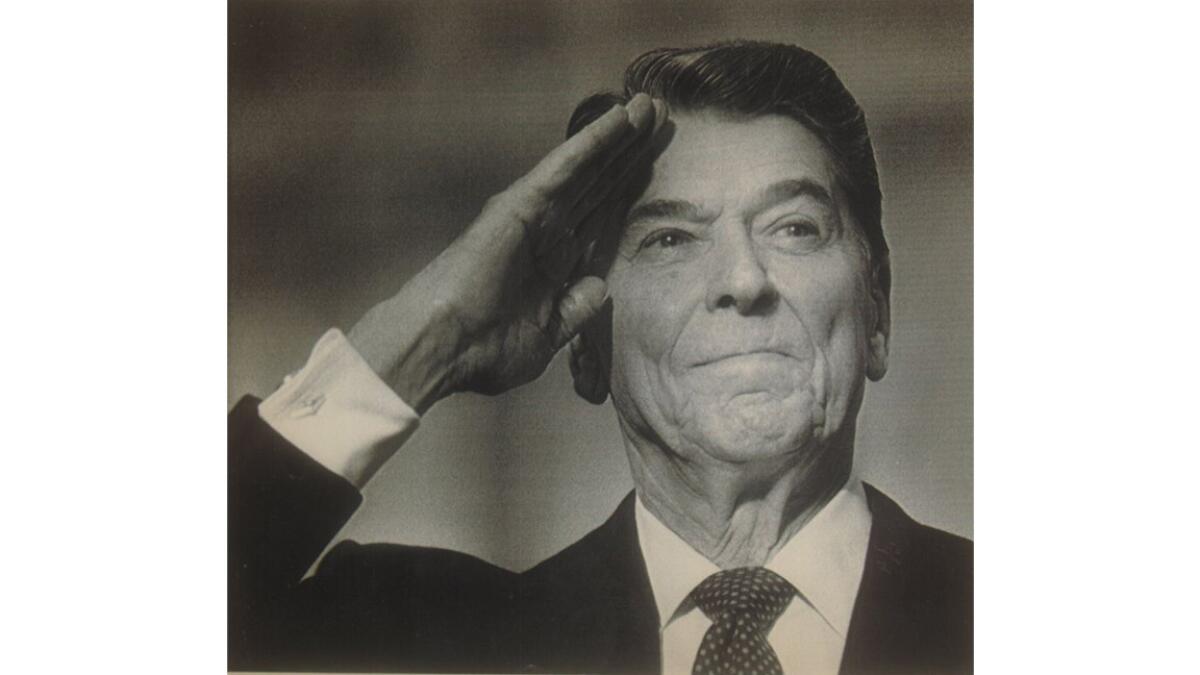

Plenty of liberals were convinced there was no way Americans would support a far-right, not-terribly-bright, washed-up-movie-actor-turned-governor running for president. (Hold those cards and letters; that’s a description of how Ronald Reagan was perceived by some of his opponents.)

“If you wanted to raid,” Nagler said, “Reagan would have been an awesome guy to support” as presumably the weakest candidate against President Jimmy Carter.

We all know how that election turned out.

But there are other reasons why the partisan hijacking of primaries is more conspiracy-minded delusion than practice.

Most voters don’t think like campaign strategists, or some political correspondents, who consume vast quantities of polling data, carefully weigh every tactical maneuver and study any slight nuance that could tip the outcome of an election. Maybe that’s why they’re less conniving than the political pros might think.

Most voters, it seems, view the election process as something to be respected and not trifled with. When they cast a ballot, Nagler suggested, they do so with a distinct sense of fair play. “They’re not looking to do mischief,” he said, “and they’re not looking to game the system.”

So fearful partisans should stop worrying about the enemy crashing their primary and doing malicious damage. It turns out that boogeyman is a no-show on Election Day.

Twitter: @markzbarabak

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.