Analysis: How California Republicans and Democrats differ from those nationally

For decades, Californians prided themselves on cutting the path to be trod later by national political figures. Ronald Reagan rose first on the West Coast and spread eastward with his election as president. The anti-tax movement likewise moved from west to east, grounded by the historic approval of Proposition 13’s property tax limitations in 1978.

This year, the state’s Democrats and Republicans are moving, in some key ways, in exactly the opposite direction from the national parties.

National Democrats, as a glance at the presidential contest demonstrates, are feeling intense pressure to move to the left. Hillary Rodham Clinton, hardly a conservative when left to her own devices, has moved left on criminal justice, immigration and economic policies as she seeks to put down a surprisingly strong challenge by an independent socialist, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

Among Republicans vying for the 2016 presidential nomination, the race to the right has taken on the appearance of a stampede. Gone is the past support of some candidates for dealing with immigrants in the country illegally, or support of more moderate policy changes on healthcare or education.

Contrast that with the positioning of California’s Democrats and Republicans.

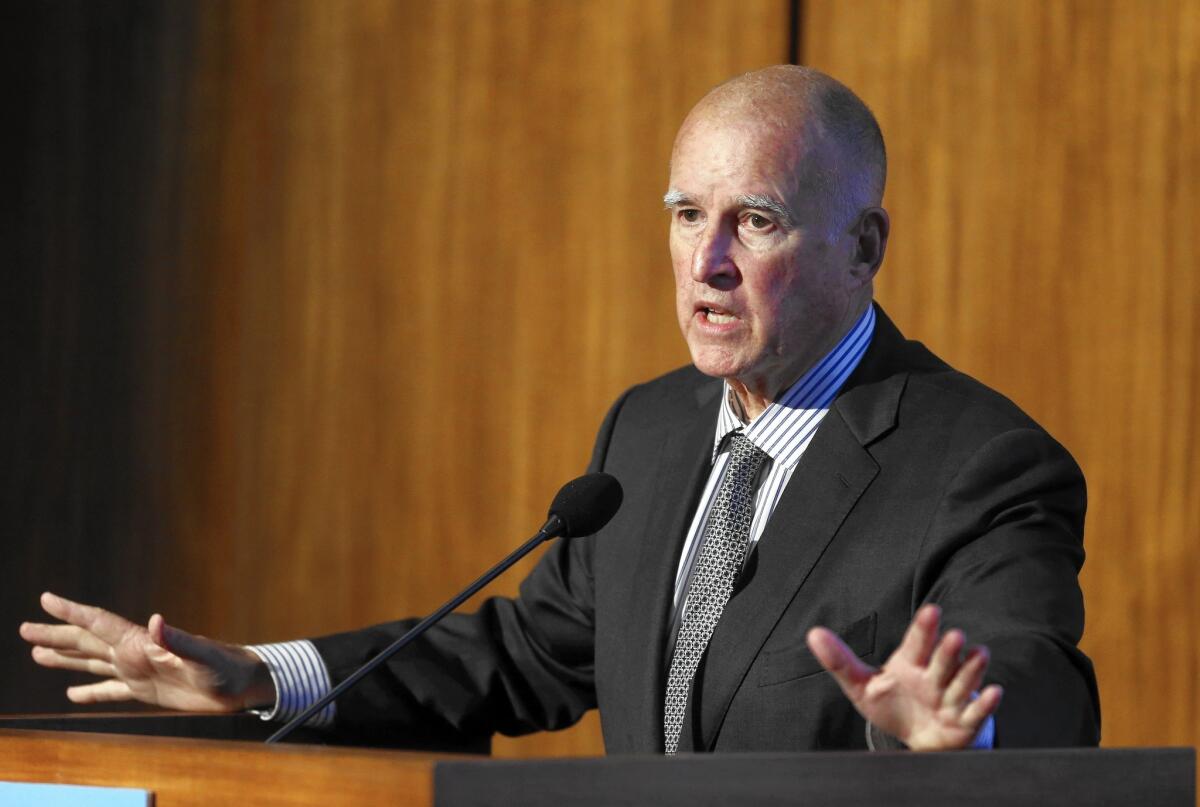

The state’s Democrats are led by Gov. Jerry Brown, who, while liberal in some respects, has served as a brake on more leftward elements of his party. An increasingly forceful presence in the party —while still a rabble-rousing minority — are those pushing conservative-for-a-Democrat positions on government pensions, organized labor and education policy.

The divergence with the nationals is even more pronounced among state Republicans. The party’s 2014 candidate for governor, Neel Kashkari, favored abortion rights and gay marriage, the almost universal opposite of GOP presidential candidates. Some may discount his positions because he was, more than anything, a sacrificial lamb. But there’s more evidence.

Earlier this year, state Republicans offered an official embrace to a chapter of Log Cabin Republicans, the gay group that previously had not been formally acknowledged. And in late September, delegates to the state party’s convention approved platform wording that Republicans “hold diverse views” about millions of immigrants in the country without proper papers. It also omitted language that said allowing them to stay “undermines respect for the law.”

The changes were symbolic but meaningful. And they run directly contrary to the stances held by many of those running to be the nation’s top Republican, and the national party as well.

California’s role as the outlier has been driven by changes in party strength, demographics and, for lack of a better scientific term, group dynamics.

Some distinctions have long been tolerated. Republicans in California often were more sympathetic to environmental causes than their counterparts elsewhere. Still, for a long period, the state and other major portions of the West were firmly in the Republican camp. (No Democrat won the state in a presidential contest between 1964 and 1992.) Now, California is determinedly Democratic in presidential contests, and it is not alone. Nevada, New Mexico and Colorado have gone to Democrats in recent contests, and Arizona looms as a future toss-up state.

In large part, those states have grown more Democratic because their populations have become younger and less white. At the same time, the national Republican Party has found its strength in the conservative South, particularly among white evangelical voters. With California out of sync with the national party on demographics, religiosity and region, the break was inevitable.

Harmeet Dhillon, vice chair of the state Republican Party, described the changes at the party’s September convention as a matter of survival.

We are doing what is right for our party. We can’t take responsibility for the national party and the national candidates.

— Harmeet Dhillon, vice chair of the California Republican Party

“Some of these issues are issues that need to be changed as our country evolves,” she said. She added pointedly: “We are doing what is right for our party. We can’t take responsibility for the national party and the national candidates.”

The difference between California Democrats and their national brethren is more nuanced. To be sure, state Democrats have been at the forefront of many liberal causes espoused now by the party’s presidential candidates. Rather than being forced by demographic differences, the Democratic schisms present now are the fallout from their statewide success.

Nationally, according to a Pew Research study last year, 32% of the nation’s voters were Democrats and 23% were Republicans, a differential of only 9 points. In California, state registration figures show that 43% of voters are Democrats, while just under 28% are Republicans — a difference of more than 15 points. That Democratic gap grows dramatically with the addition of independent voters, who make up almost a quarter of the electorate and, for the most part, are reliable Democratic allies.

Historically, a group becomes so dominant because it houses people with disparate views. But inevitably, fissures form. Those fissures are most likely to be seen in the run for governor in 2018, particularly if announced candidate Gavin Newsom, the lieutenant governor, is challenged by former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, long at war with teachers unions over changes he says must be made in the state’s education system.

“I want to speak to Democrats,” Villaraigosa said at a June meeting of the U.S. Conference of Mayors in San Francisco. “You all have got to have the courage ... to stand up; you can’t be afraid to stand up for the civil rights of poor kids.”

Stand up, he might have said, against one of the party’s most powerful benefactors: teachers. It was the kind of message that California will hear more and more, and national Democrats are likely to hear not at all.

Twitter: @cathleendecker

For more on politics, go to www.latimes.com/decker and www. latimes.com/politics.

ALSO:

California GOP softens its message on immigration in a bid for survival

Third GOP debate appears to broaden field, not winnow it

Who fell flat? Watch Decker, Mehta analysis of the Republican debate

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.