Lawsuit contends the California bullet train project is violating state law

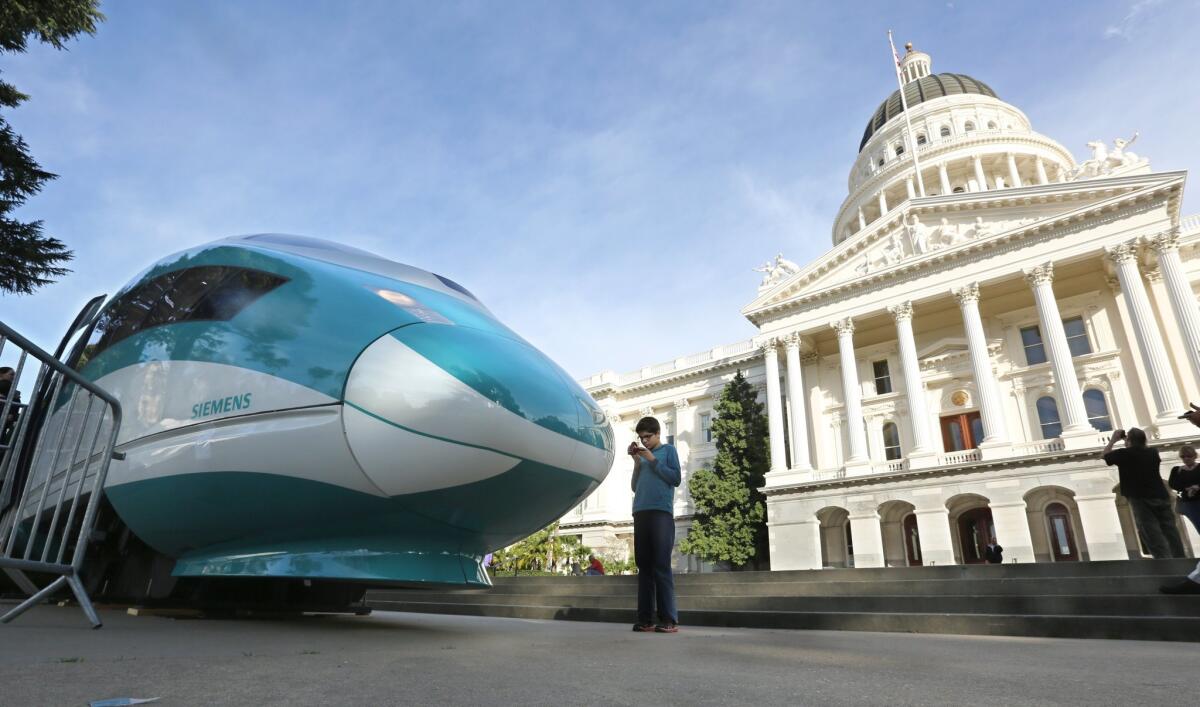

More than a dozen lawsuits have been filed against the state’s bullet train project. Above, a full-scale mock-up of a high-speed train is displayed at the Capitol in Sacramento in October.

The California bullet train project violates state law because it is not financially viable, will operate slower than promised and has compromised its design by using existing shared tracks in the Bay Area, attorneys for Kings County and two Central Valley farmers argued Thursday in Sacramento County Superior Court.

The lawsuit asserts that the state’s plans for the Los Angeles to San Francisco high-speed rail link violate restrictions placed on the project under the $9-billion bond act that voters approved in 2008.

Read the latest Essential California newsletter >>

The project has faced more than a dozen lawsuits, brought by churches, corporations, farmers, irrigation districts and government agencies. But the suit by Kings County and farmers John Tos and Aaron Fukuda has emerged as the most serious challenge to the entire project. The legal challenges have contributed to delays that have now put the project more than two years behind schedule.

The suit asks to halt funding for construction and land acquisition, allowing spending only to develop an alternative plan. A ruling is supposed to be issued within 90 days.

Judge Michael Kenny had asked the attorneys to focus on five technical questions revolving around the state’s compliance with the bond act.

Stuart Flashman, who represented the plaintiffs, described a number of alleged violations of the bond act restrictions.

One involved the rail authority’s plan to use existing commuter and freight rail tracks through the San Francisco Bay Area rather than the dedicated high-speed rail tracks it had planned and featured in its 2005 and 2008 environmental reports. Flashman said the bond act required that the system be consistent with those environmental reports.

Arguing for the state, Deputy Atty. Gen. Sharon O’Grady denied that the project is violating the restrictions, arguing that voters were probably not familiar with whether the system would have its own tracks or share existing tracks in the Bay Area.

O’Grady said the possibility of using shared tracks was raised in the environmental reports, and she noted that the change in plans cut the cost to its current $68 billion from $98 billion.

Flashman contended that the completed system on the shared tracks will never meet the requirement to travel between San Francisco and San Jose in 30 minutes, arguing that the state also tried to save three minutes by having the train stop short of the Transbay Terminal in downtown San Francisco.

He said the completed system would also fail to get from San Francisco to Los Angeles in two hours and 40 minutes. The only way the state could meet that would be to travel through cities at 220 mph, when it had assured local communities that the train would slow to a maximum of 125 mph, and to travel at full speed as it descended thousands of feet to the Central Valley from the Tehachapi Mountains.

O’Grady dismissed a number of Flashman’s assertions, saying Flashman simply disagreed with the rail authority experts. O’Grady also suggested that the Legislature did not need to satisfy the trip time requirements when it approved the track sharing. Flashman said a bond act can only be changed by voters.

The bond act placed a number of financial requirements on the project, including a prohibition on operating subsidies and a stipulation that it had to identify all the money to build an operating segment before it could begin construction.

“Until you have money that says we can build this, it’s not financially viable,” Flashman told the court.

Flashman argued that the state’s ridership studies never examined the economics of an initial operating segment that would run from Burbank to Merced, but instead used ridership estimates for the entire system.

Rail authority spokeswoman Lisa Marie Alley said the suit was brought “by a handful of opponents to stop the project and cause delays and cost overruns at the expense of taxpayers.”

Alley said that the authority is building a system that “complies with the voter-approved requirements” of the bond act and that the system will meet the required travel times and have sufficient revenue to cover operating costs.

One other legal issue debated Thursday involved whether the legislation that authorized the bond act, AB 3034, applied only to the use of the bond money or restricted the design no matter what source of funds were used. Flashman contended the restrictions should apply to all sources of money, including federal grants and greenhouse gas fees that the state now taps.

During an earlier phase of the case in 2013, Kenny had ruled that the state lacked an adequate funding plan necessary to sell the bonds. An appeals ruling the following year reversed that finding, but warned that substantial legal issues still loomed. The state has not attempted to sell the bonds for construction since then.

Ralph Vartabedian reported from Los Angeles and special correspondent Marc Vartabedian reported from Sacramento.

ALSO

Bullet train’s first segment, reserved for Southland, could open in Bay Area instead

Bullet train may take longer to build but cost less, official says

What’s behind a bid to shift dollars from the bullet train to water projects

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.