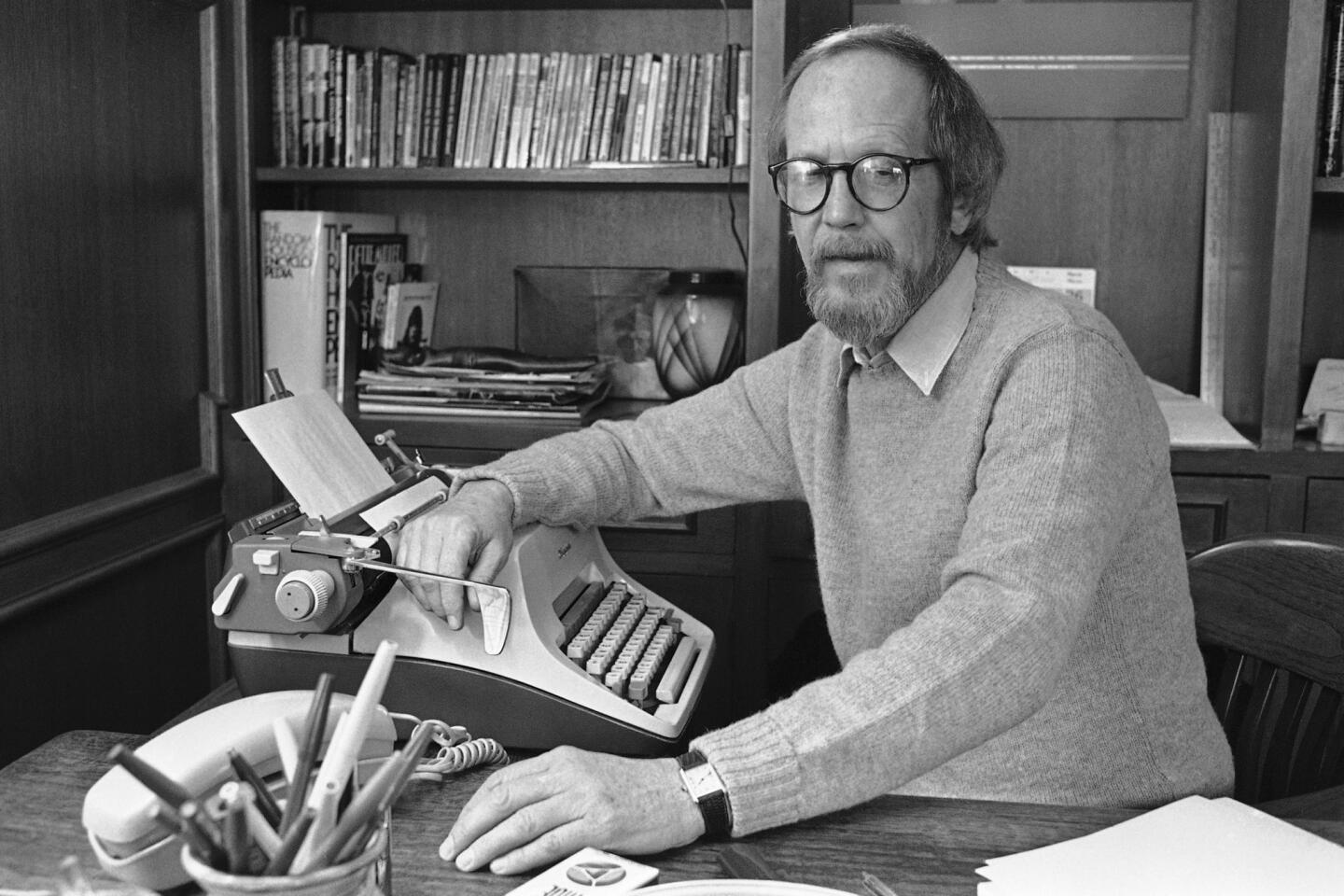

William H. Ginsburg dies at 70; Monica Lewinsky’s attorney

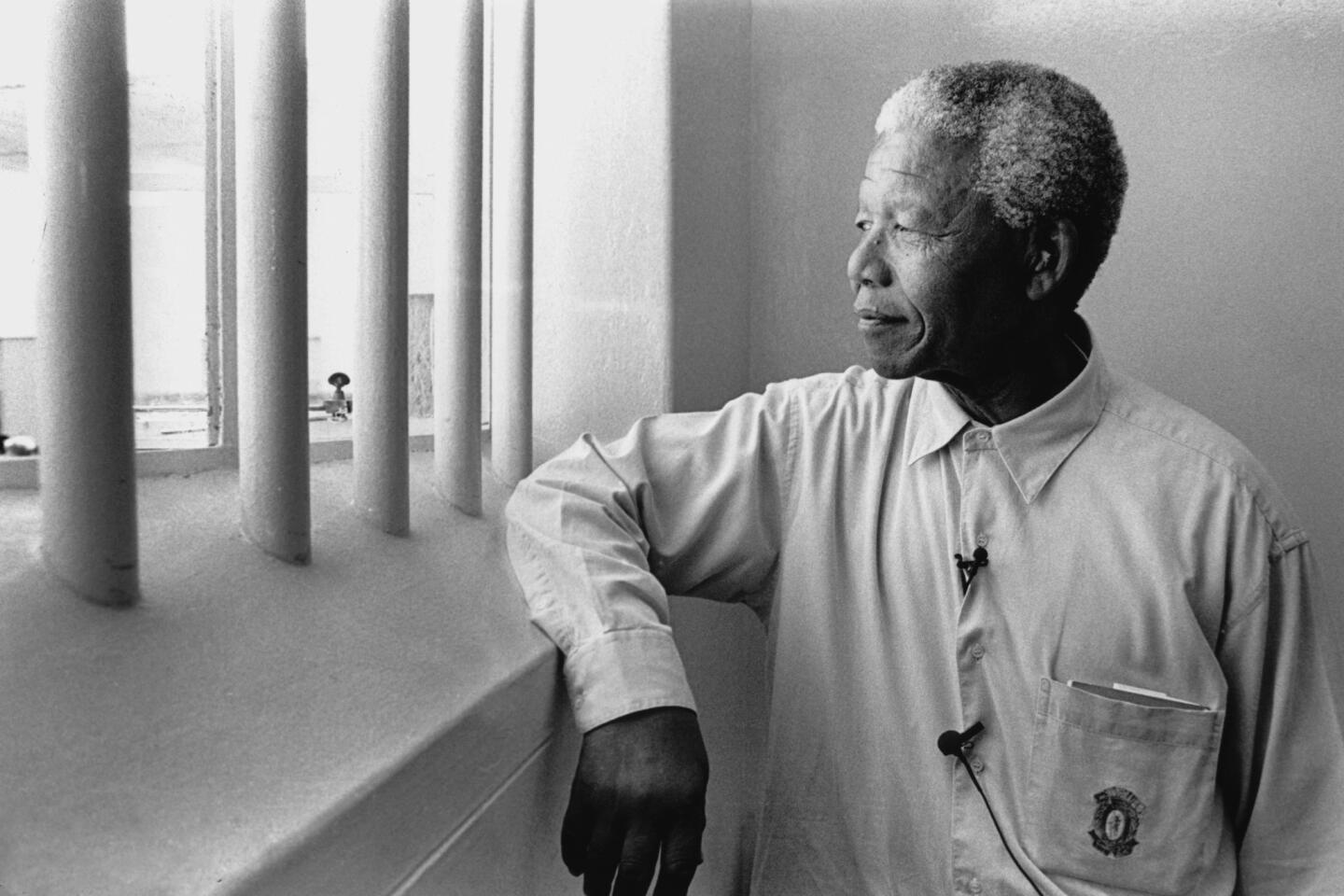

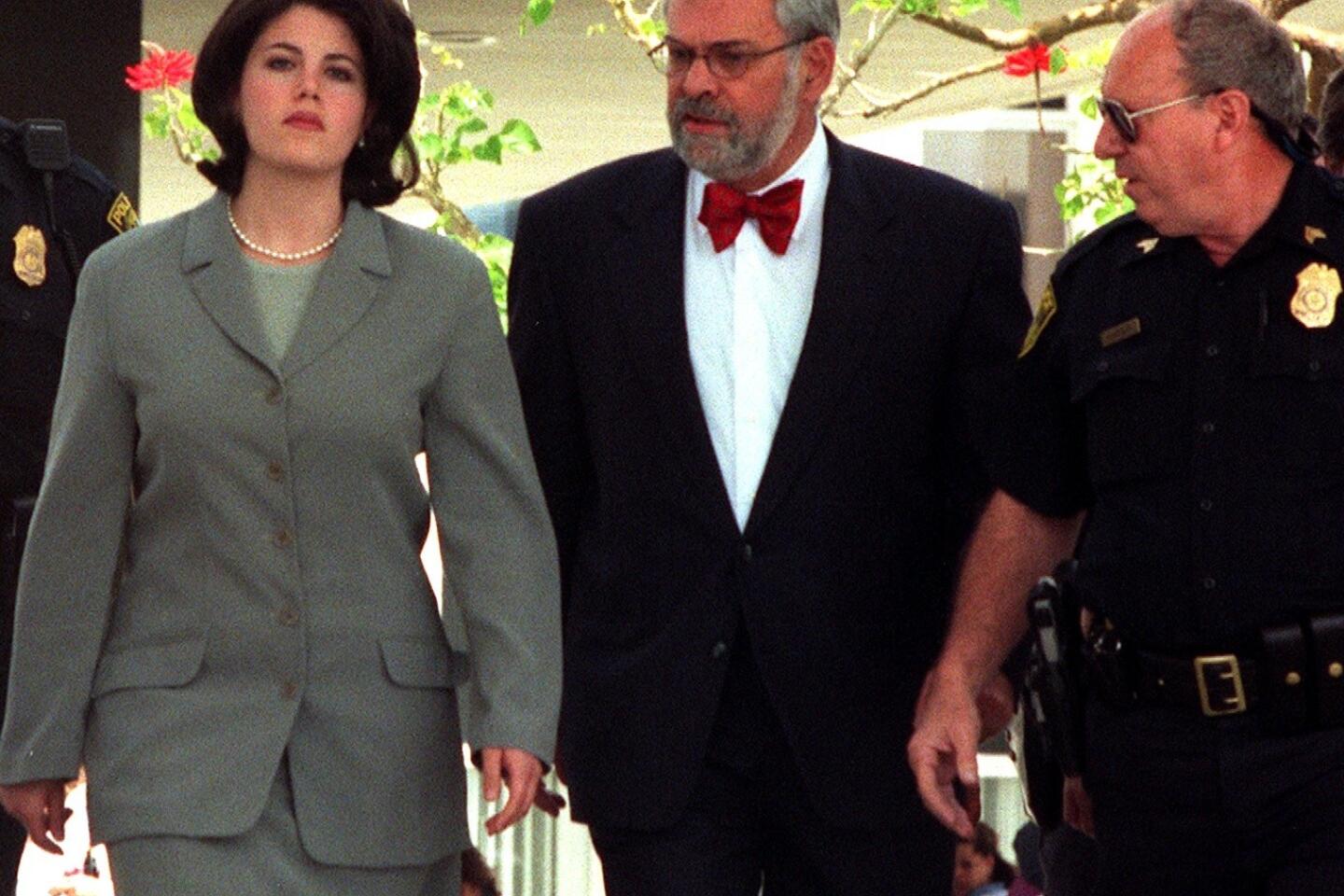

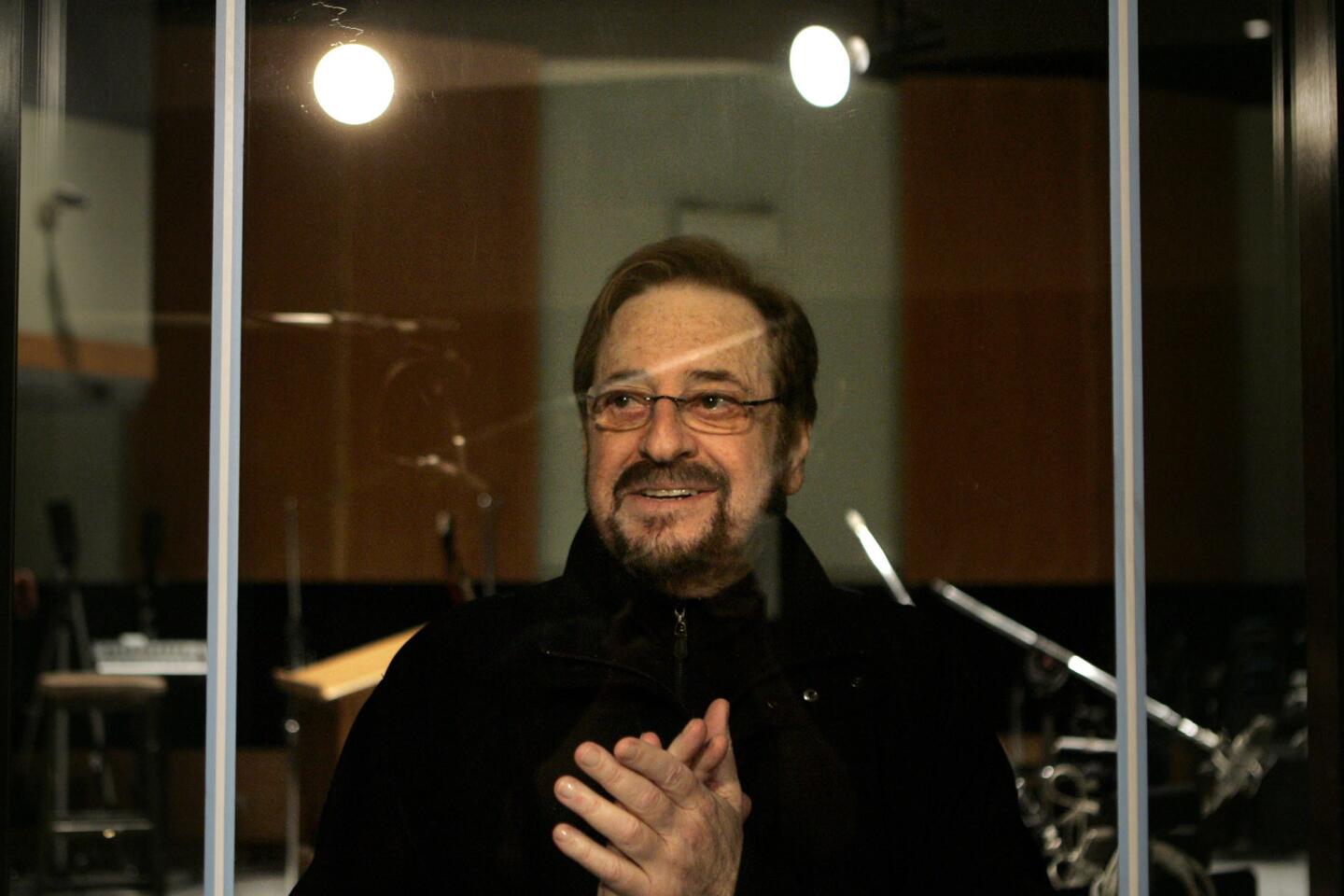

William H. Ginsburg, a seasoned medical malpractice attorney who bolted to national prominence in the brutal arena of Washington politics as Monica Lewinsky’s lawyer, died Monday at his home in Sherman Oaks. He was 70.

The cause was cancer, said his daughter-in-law Virginia Ginsburg.

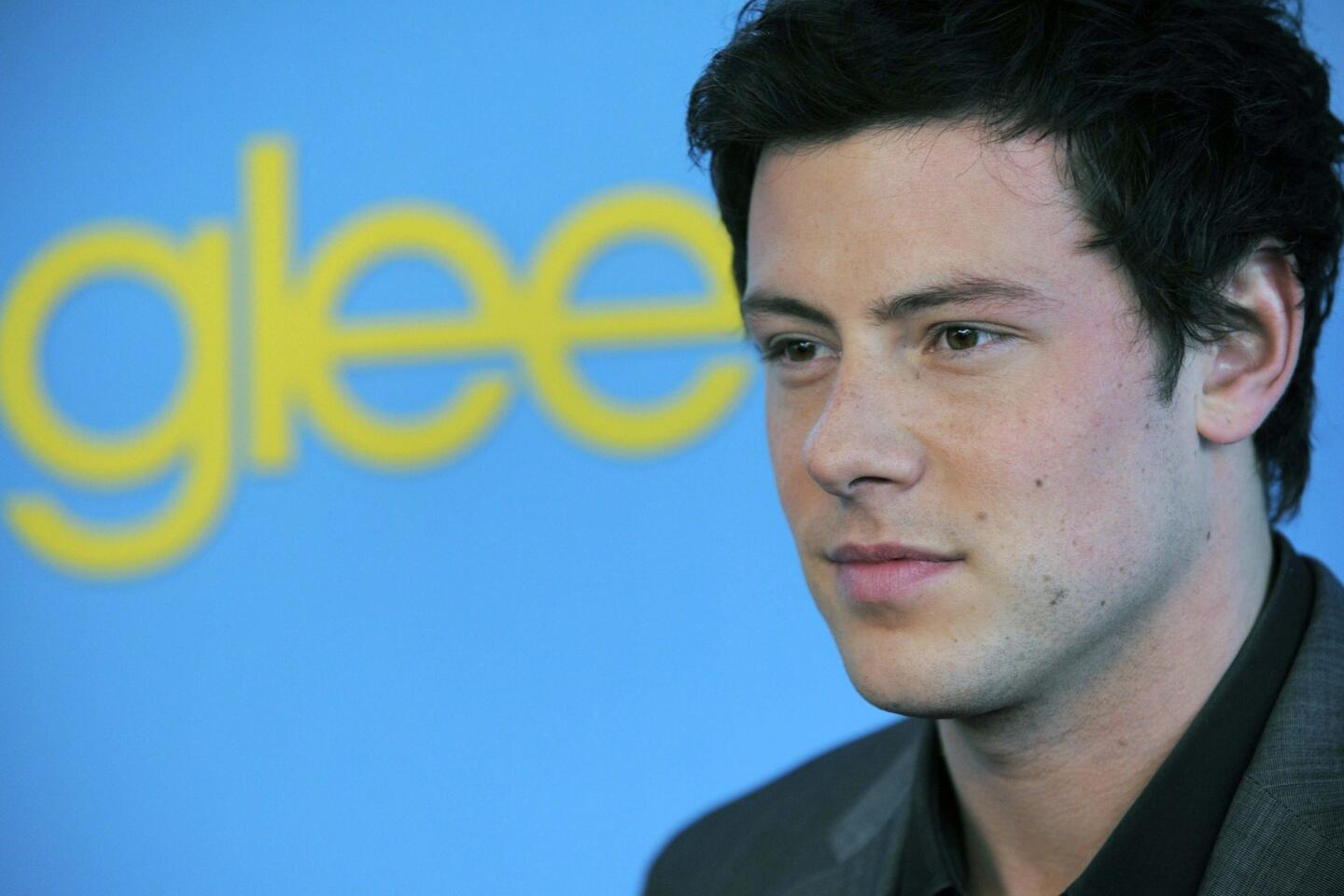

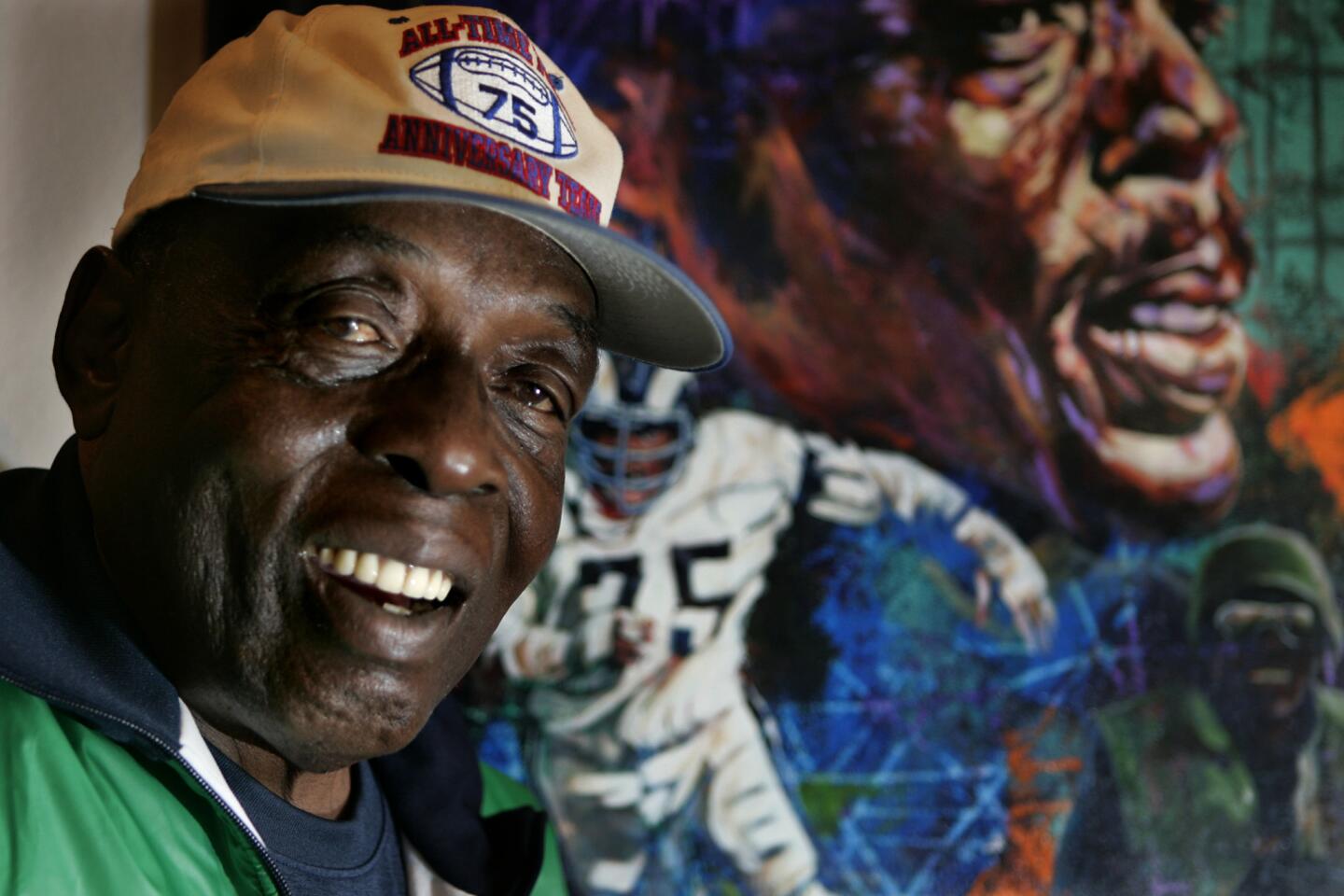

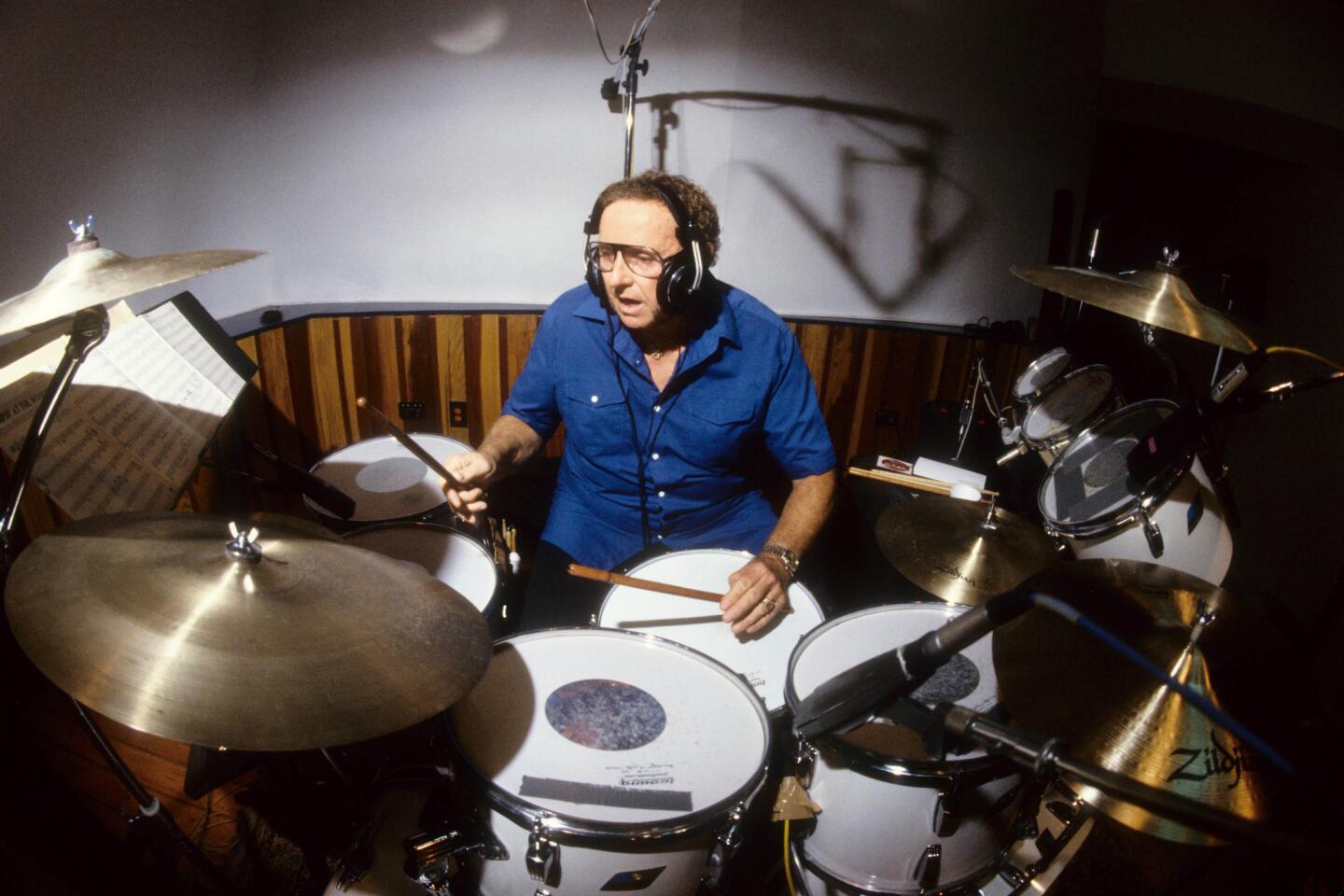

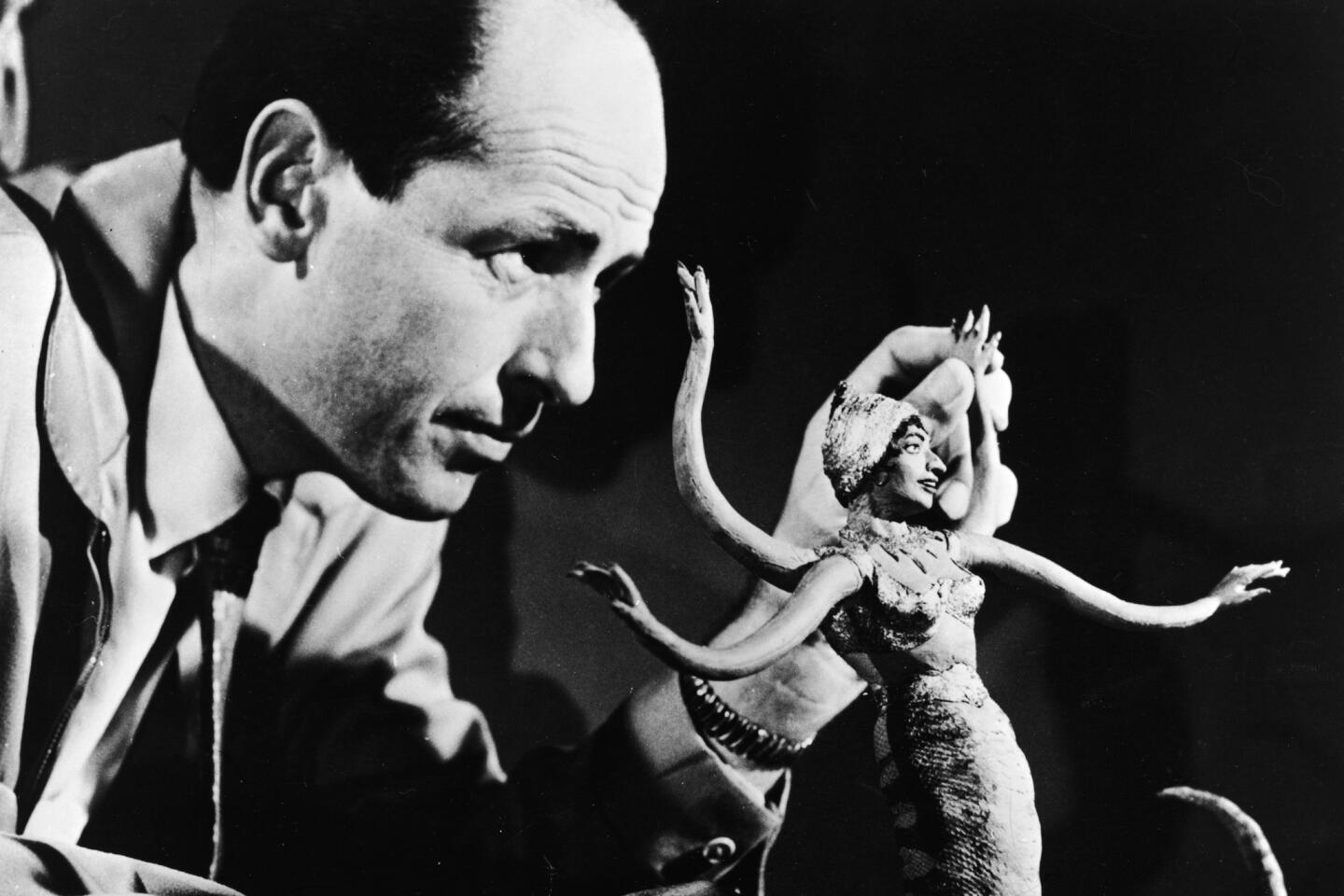

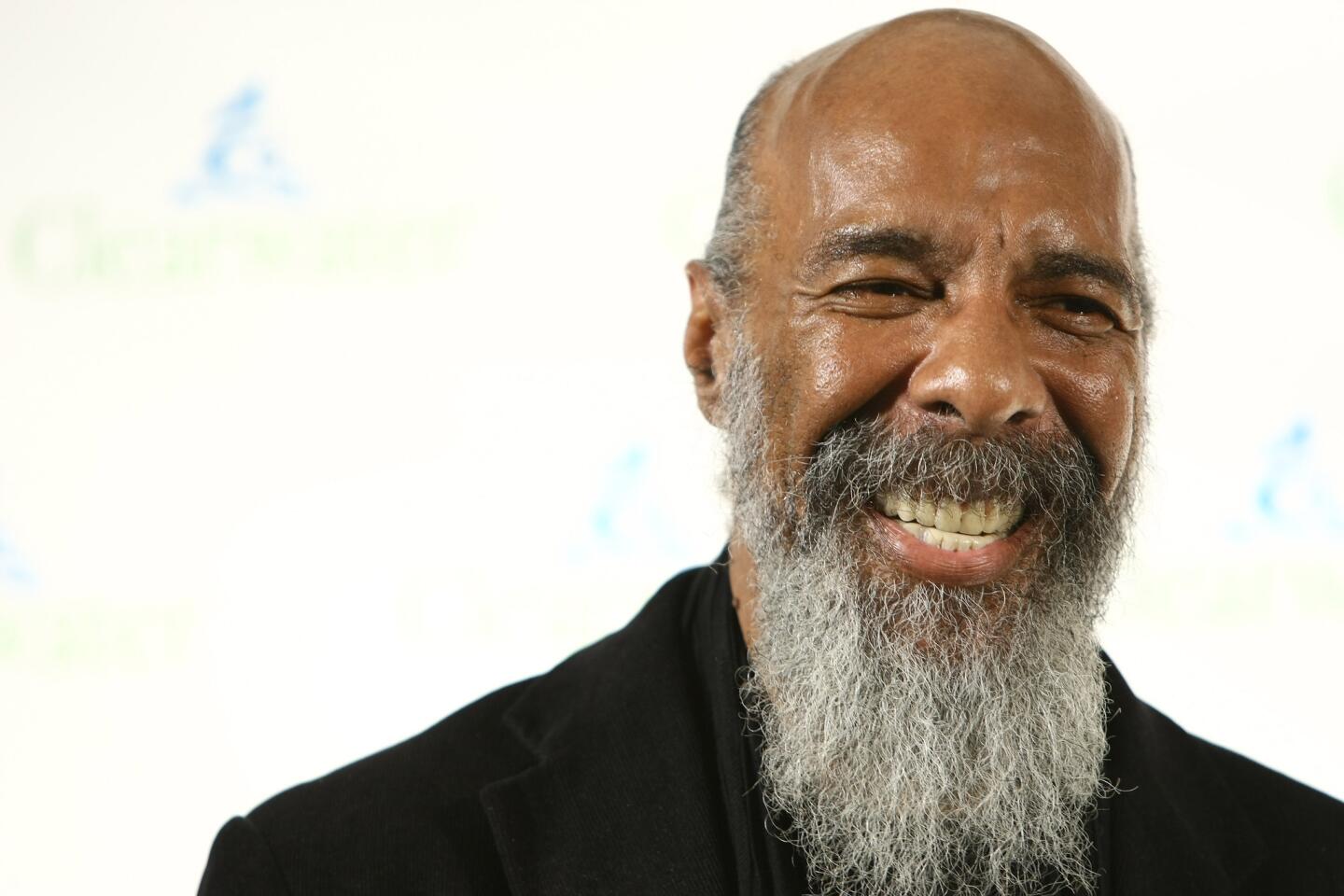

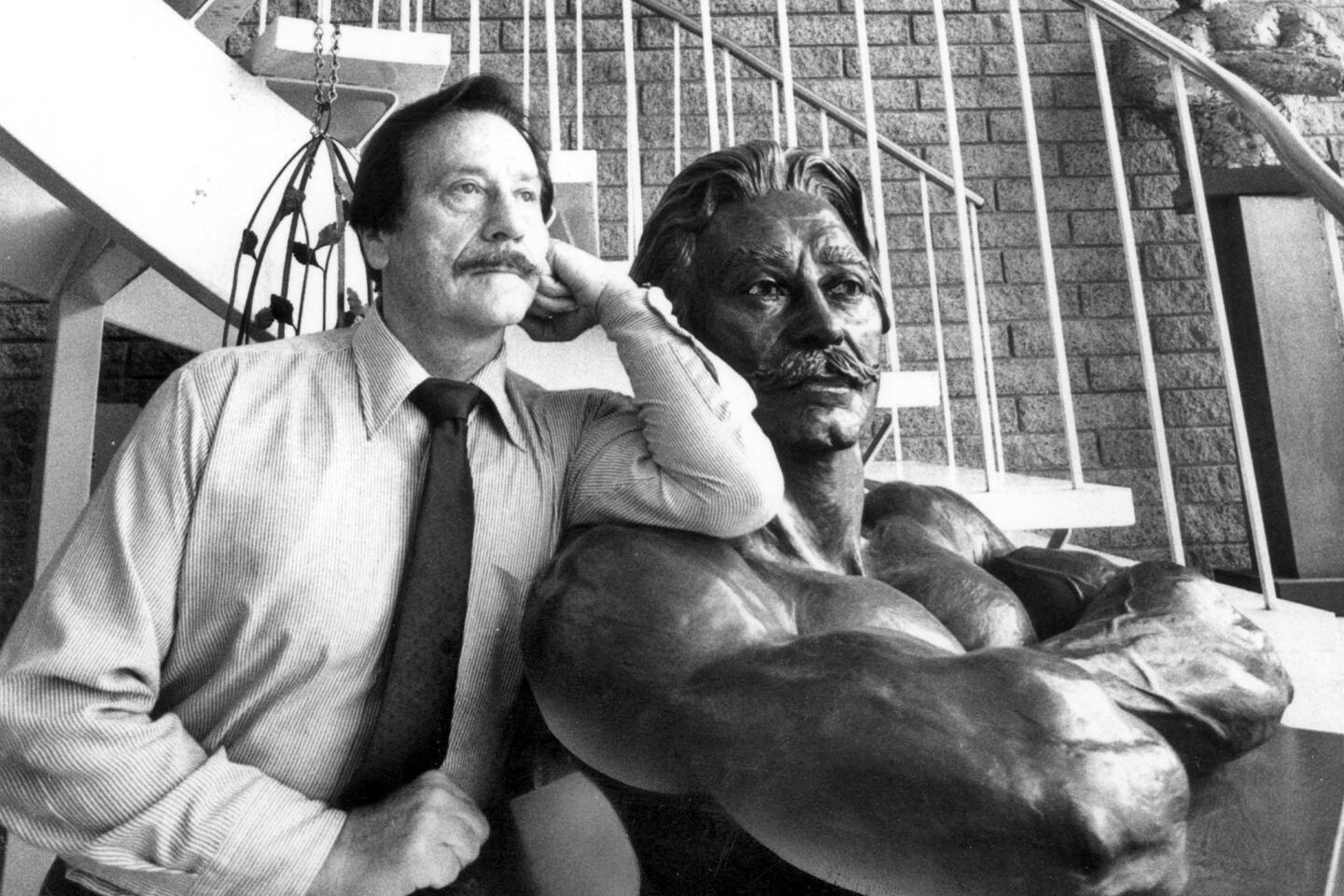

In 1998, Ginsburg was a senior partner in a Beverly Hills medical malpractice firm, where he had a sterling track record defending unpopular clients. He represented the physician accused of covering up the cause of entertainer Liberace’s death from AIDS and the cardiologist who examined Loyola Marymount University basketball star Hank Gathers just before the young player’s sudden death during a game.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

He also defended a Glendale hospital in a case that wound up helping to establish the foundation for a patient’s right to die.

“He was a superb jury trial lawyer,” said Los Angeles attorney George Stephan, who worked with Ginsburg for 25 years. “His cases were very difficult ... but he was just very insightful about what was important to the jurors and the justice system.”

It was Ginsburg’s longtime friendship with Lewinsky’s physician father that landed him in the middle of the biggest scandal to hit Washington since Watergate.

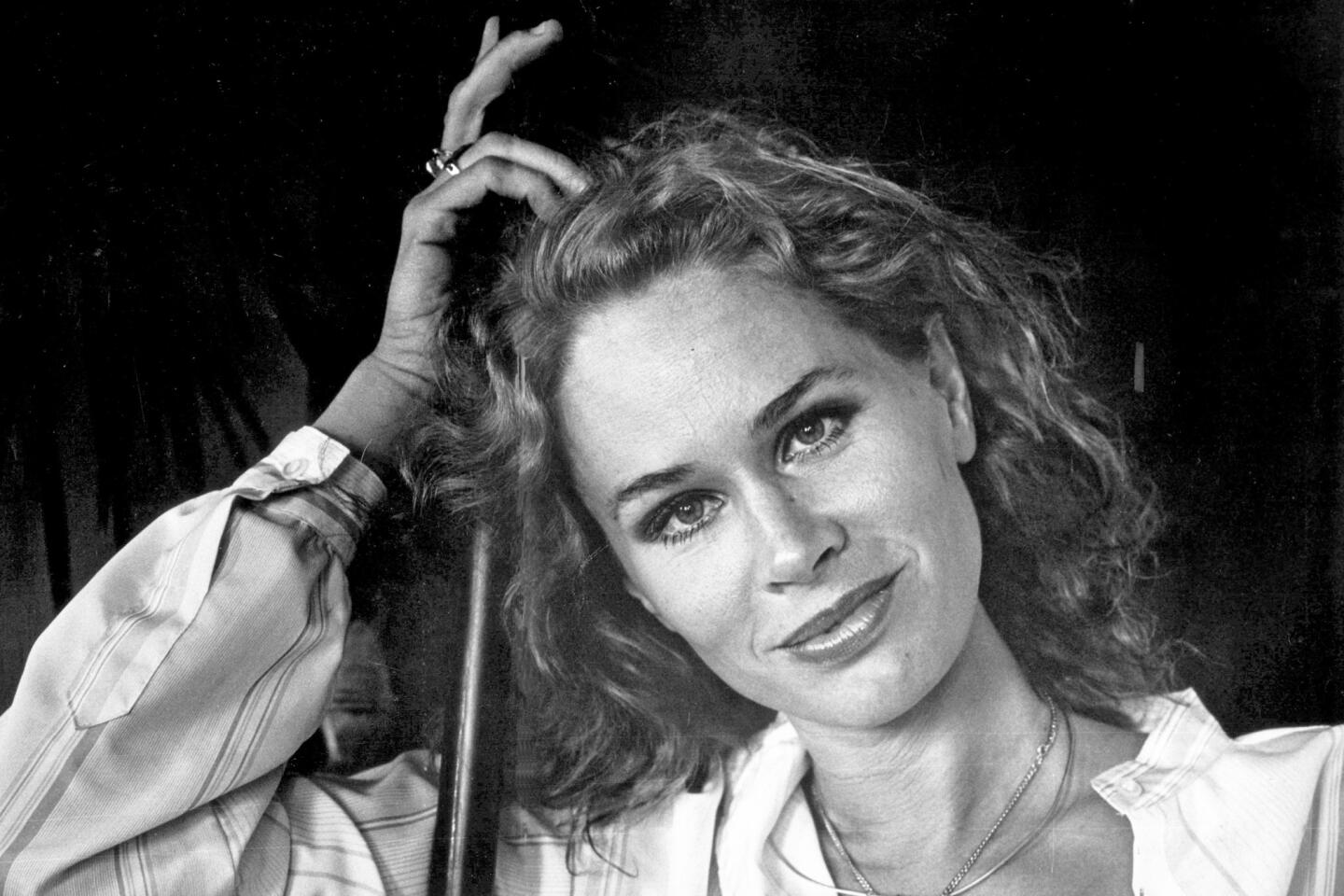

Lewinsky was the former White House intern who found herself in legal jeopardy for allegedly lying under oath about having sex with President Clinton.

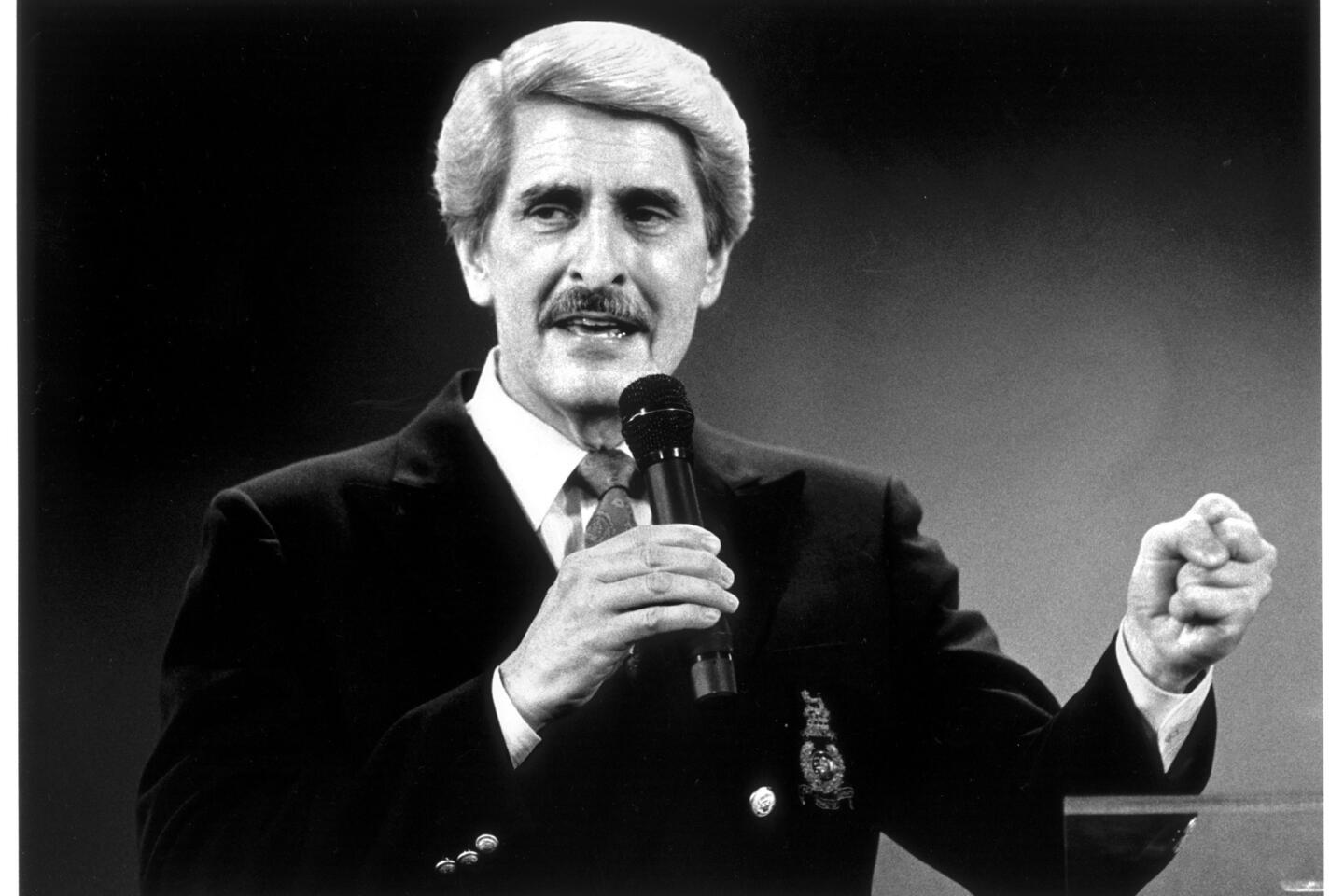

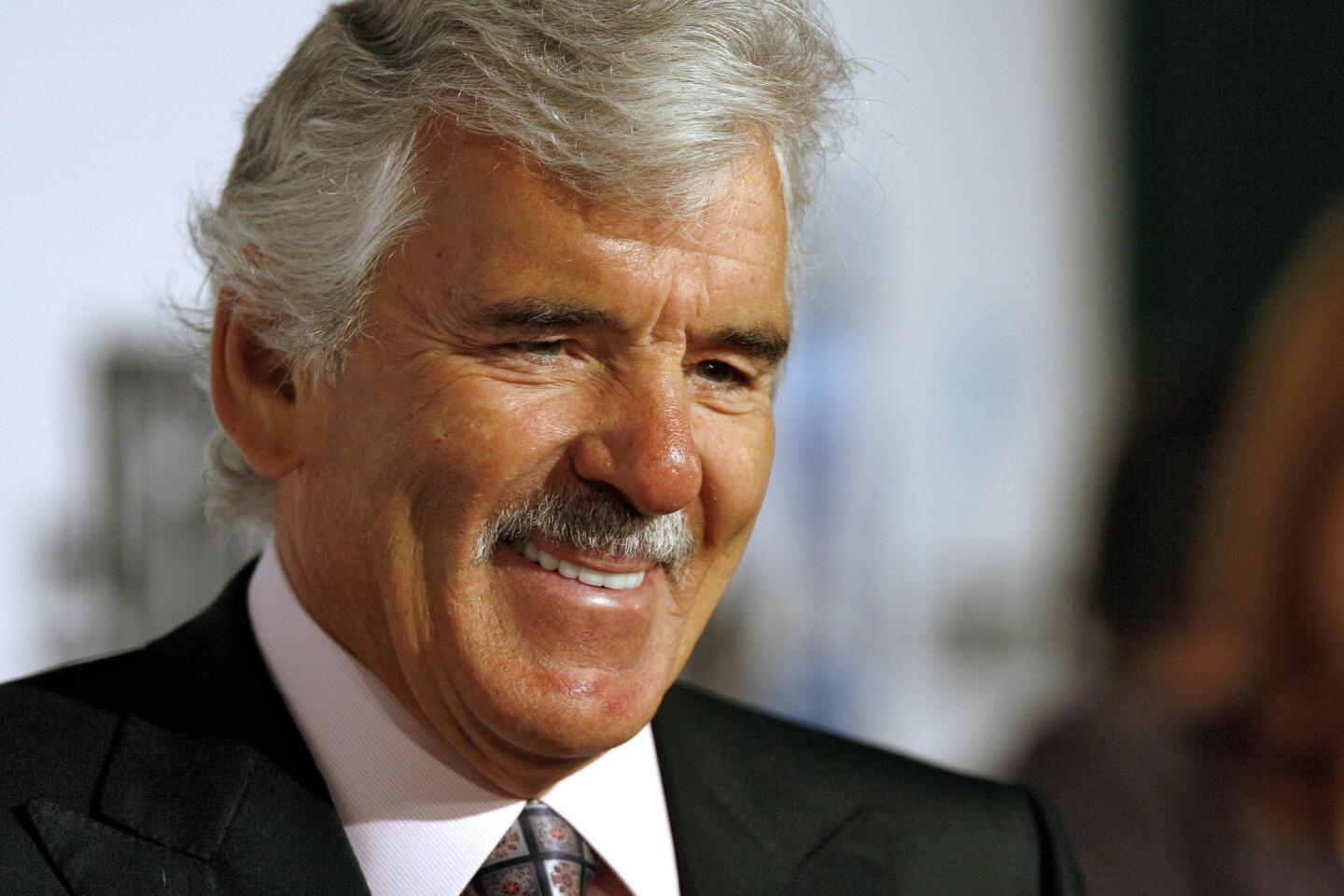

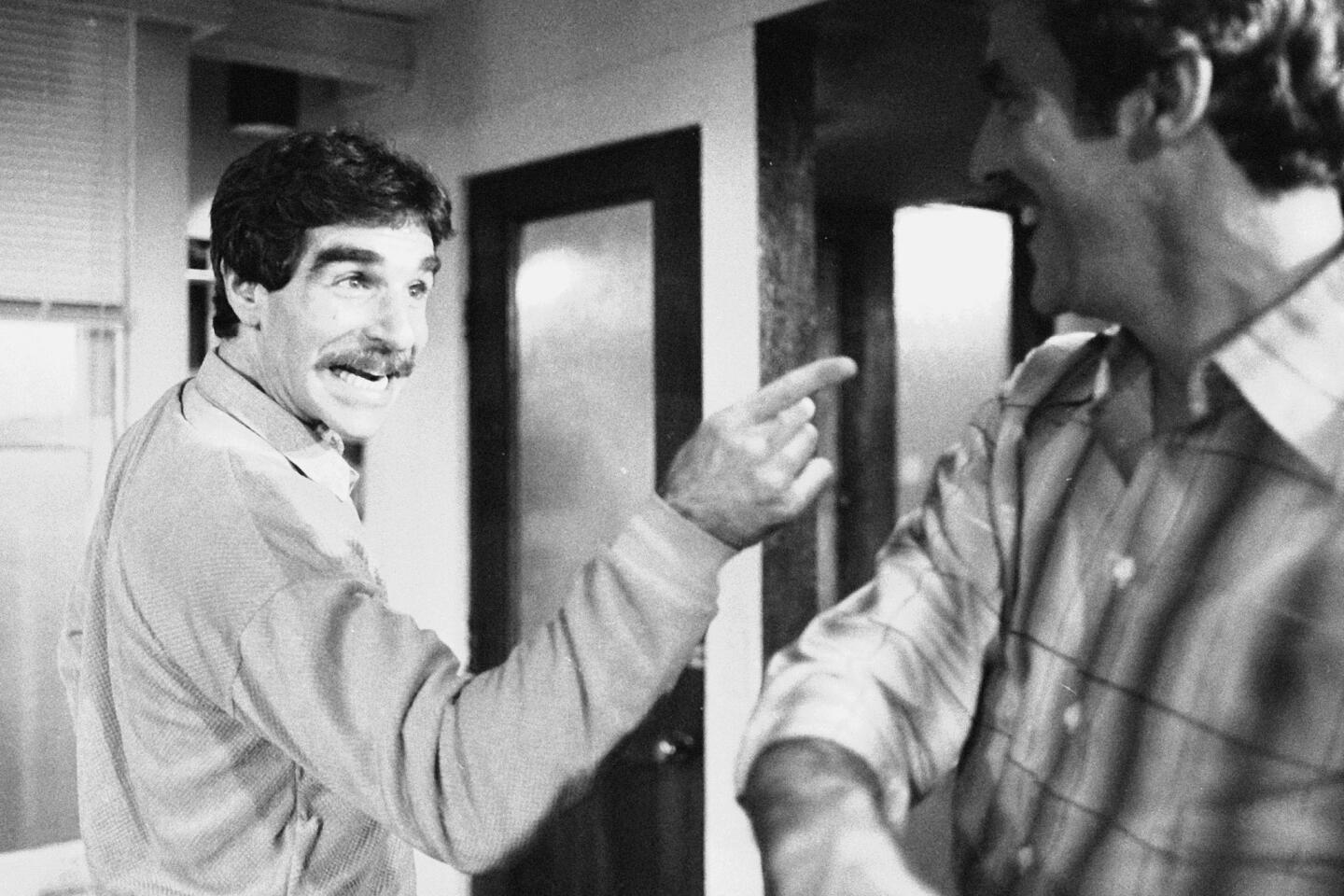

Shortly after the scandal broke in January 1998, Ginsburg agreed to represent her but quickly became a target himself, drawing barbs from prominent critics accusing him of amateurish missteps, including his early failure to secure immunity for his client.

On Feb. 1, 1998, he set a record for appearing on all five major Sunday political talk shows, fueling criticism that he was making too many public statements, including some that appeared to undermine Lewinsky’s credibility.

She avoided prosecution but not a grand jury appearance, during which she gave eyebrow-raising testimony about Clinton, a blue dress and a cigar.

Ginsburg said he would have relished the chance to take on independent counsel Kenneth Starr in front of the public and a jury. But after half a year in the media glare, he turned Lewinsky over to a new defense team and returned to his private practice with a sense of relief.

“If you submitted the entire Bible to the press and one page had the word ‘sex’ printed on it, the press would focus on that word, rather than the other wonderful truths that we find in that book,” he told The Times after leaving Washington in June 1998.

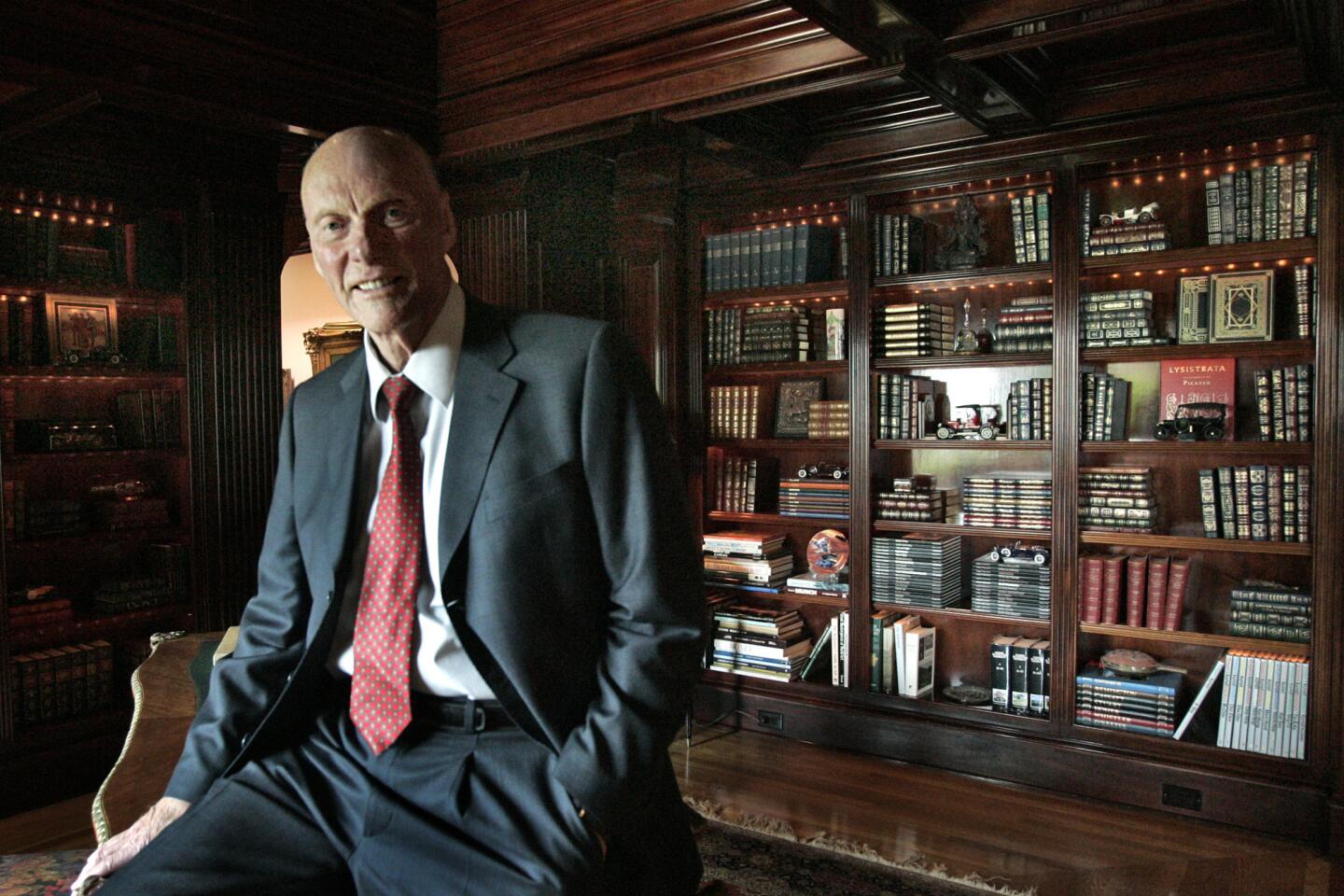

The son of a lawyer who worked on Lyndon Johnson’s Senate staff, Ginsburg was born in Philadelphia on March 25, 1943. He moved to Los Angeles with his family in the early 1950s. After graduating from Hamilton High School, where he was active in the theater department, he studied political science and drama at UC Berkeley. He later channeled his theatrical impulses into a different field, earning a law degree from USC in 1967 and passing the bar in 1968.

Among his first clients were conscientious objectors, even though he was then serving in the military as a member of the Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps. Later, he represented many of the country’s largest pool and spa builders from lawsuits over swimming accidents, winning the majority of those cases even against the most sympathetic of plaintiffs left with paralysis and other severe injuries.

In the mid-1980s he defended Glendale Adventist Medical Center in a $10-million lawsuit brought by William Bartling, who had five serious diseases and wanted to be disconnected from the machines that were keeping him alive. The hospital refused to accede to his request and a state court agreed that turning off the respirator would be tantamount to aiding a suicide.

The state court decision was appealed but the night before the hearing, Bartling died from his illnesses, giving Ginsburg solid ground to ask for the case to be dismissed.

Instead, he urged the court to proceed and it wound up ruling that Bartling had the constitutional right to refuse treatment. Ginsburg, by seeking clarity in the law for the medical providers he represented, “took the high road,” Griffith Thomas, the opposing attorney, told The Times in 1998.

Stephan, who worked with Ginsburg on the case, said that his former colleague “in a sense ... didn’t lose the case. He won because what was important to doctors was certainty in the law and a provision that would allow the patient, doctors and the family to all work together for an outcome. That was important to the people Bill was representing.”

During his career, Ginsburg tried more than 300 cases, many of them involving complex medical procedures and vexing issues of liability. None, however, brought him as much attention as the Lewinsky sex scandal. He often referred to his famous client as “poor little Monica” and belittled the forces arrayed against her. “I had to ask myself,” he said on CNN, “‘How many FBI agents and U.S. attorneys does it take to handle a 24-year-old girl?’”

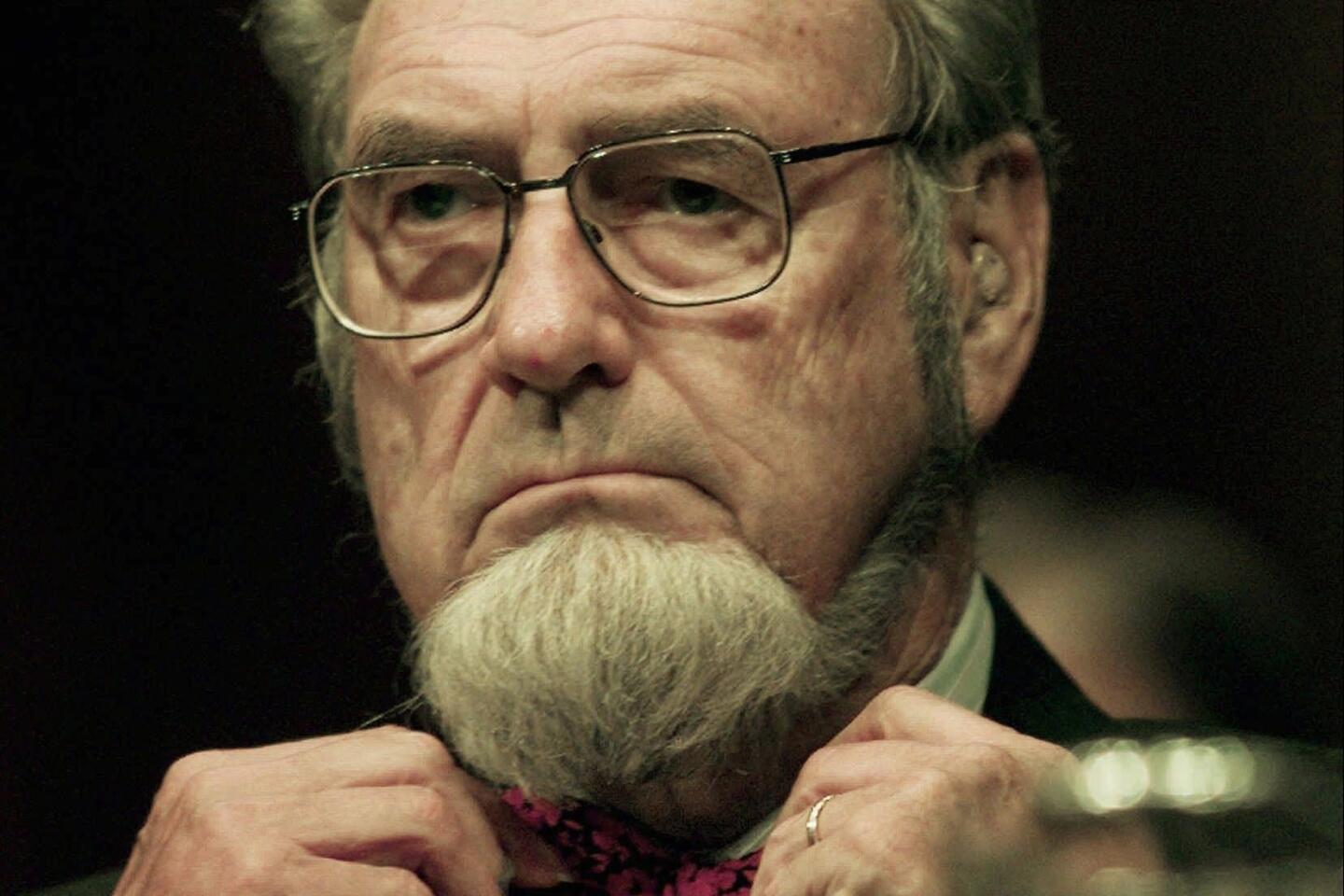

Later, in an open letter to Starr in California Lawyer magazine, he wrote: “Congratulations, Mr. Starr! As a result of your callous disregard for cherished constitutional rights, you may have succeeded in unmasking a sexual relationship between two consenting adults.”

He bowed out of the case two months before Lewinsky’s grand jury date, saying his public sparring with Starr had diminished his effectiveness.

Ginsburg appeared unruffled by the many attacks on his legal competence in a hardball criminal case. “Bah, humbug!” he said in the 1998 Times interview. “After you have handled a few high-profile and high-pressure jury trials, then come back and comment. Until then, may I suggest that you curb your tongues and your criticism.”

Retiring a few years ago after ending his career as a private mediator and arbitrator, Ginsburg is survived by his wife, Laura; children David, Maxwell and Sasha; his mother, Sylvia; a brother, Kenneth; and two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.