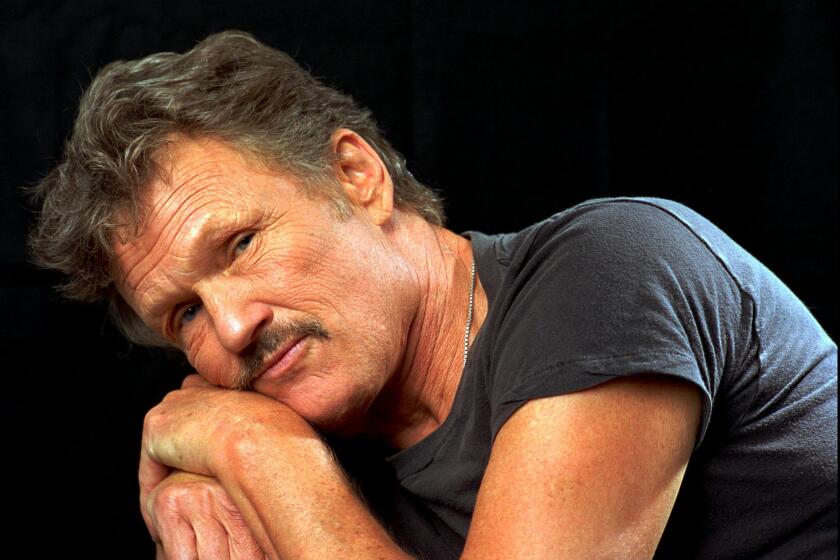

Warren Miller, the ski bum whose films made him king of the slopes, dies at 93

Freezing in a cramped trailer, shooting rabbits for dinner, slurping a gruel of ketchup and oyster crackers: Warren Miller’s early 20s would have been downright Dickensian if they weren’t so much fun.

Miller was a ski bum before that required a trust fund and four-wheel drive. In the late 1940s, when just 15 or so ski lifts threaded their way up the mountains in the West, Miller and a buddy planted themselves for the winter in a parking lot at the ski resort in Sun Valley, Idaho. They snuck onto the hill without paying, met girls, held parties, and had a marvelous time — a pattern he repeated, and then repeatedly lauded, over more than half a century.

Though he once boasted that he had “probably worked 10 hours in my entire life,” Miller was a prolific maker of popular films of expert skiers soaring over cliffs and novices falling off chairlifts. He appeared in most of them, peppering his narration with goofy jokes and homespun inspiration: “Always remember,” he would tell viewers: “If you don’t do it this year, you’ll be one year older when you do.”

Miller, who released a 90-minute movie every year for more than five decades and built a media business that included commercials and promotional films, died of natural causes Wednesday at his home on Orcas Island, Wash., where he had lived with his wife Laurie since 1992. He was 93.

In mountain towns across the country, his films used to be community events, drawing the lowliest lift attendants and the loftiest resort executives. In cities miles from the nearest snowflake, clamoring ski clubs saw them as harbingers of the fantastic season to come.

Whether it was “Anyone for Skiing?” (1957), “Ski Scene” (1967), “In Search of Skiing” (1977), “White Winter Heat” (1987), or “Snowriders 2” (1997), the formula was simple: thrills, chills, funny footage of women skiing in bikinis, or men in koala bear outfits — and timing. “The secret,” he told The Times in 1999, “is to bring the films to town before the snow starts falling.”

“That’s why we’ve been able to make the same film 50 different times,” he said. “It jump-starts the season.”

In his later years, Miller had little or nothing to do with the films that bore his name. In 1983, he sold a half-interest in his company, Warren Miller Entertainment, to a concert promotion firm. Six years later, Miller’s son Kurt and a partner bought the company and kept it until 2002. It has had several owners since. He hosted a series of lectures titled “An Evening With Warren Miller” in the Seattle area in 2010.

In 2009, Miller told the New York Times that he hadn’t seen the last few Warren Miller movies; with hard-driving rock soundtracks and a focus on extreme snow sports, they’d lost their appeal to him, he said.

Born in Los Angeles on Oct. 15, 1924, Miller grew up in Hollywood. He dabbled in sports, hitchhiking to the beach in Santa Monica and taking home movies of his surfing pals.

At 18, he joined the Navy, serving in the South Pacific during World War II. Back home, he attended classes at USC but wound up hitting the road. In 1946, he and his friend Ward Baker pulled into Sun Valley, hauling an eight-foot long, four-foot high teardrop-shaped travel trailer behind Miller’s 1937 Buick.

“It looked like the deep-freeze version of the ‘Grapes of Wrath,’“ Miller wrote in his 1958 memoir, “Wine, Women, Warren and Skis.”

They stayed the better part of three ski seasons.

Legendary skier Otto Lang, the head of the Sun Valley ski school, eventually hired Miller as an instructor and became a lifelong friend.

“I knew of his existence,” he told the Seattle Times in 1999, “chasing down the mountain without a lift ticket, the lift attendant and the ski patrol in pursuit. Warren was … there’s a German word for it — lebenskuenstler — an artist in artful living, an artful dodger.”

Miller also impressed a couple of ski students who were executives with Bell & Howell, a firm that made motion picture equipment. They gave him one of their company’s 16-millimeter cameras and nudged him down the trail to his calling. The students were Harold Geneen, later head of ITT Inc., and Charles Percy, later a U.S. senator from Illinois.

With investments of $100 each from four friends, Miller made his first film, “Deep and Light” at Lake Tahoe’s Squaw Valley. It was a modest production, with sound courtesy of his grandmother’s tape recorder and music from a church organ. Miller netted $7 at its first showing, in 1950, but he was off and running.

“I always had more ambition than cash, but no matter what happened I kept grindin’ the pictures out,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1999.

Each year, there was more to be shot: more death-defying jumps, exploding doghouses, nuns in full habit, and red-cheeked toddlers — all on skis. In town after town, Miller introduced his movies in person. One year, he stayed in more than 200 hotels. In less flush times, he slept in his old Chevy van.

Looking back, he said his years on the road taught him some valuable lessons.

“I learned that you never cook tuna on a Coleman stove in the back of a van when you’re wearing the tweed suit you’re going to wear to a show,” he told the Washington Post in 1986.

It wasn’t all laughs. In 1953, Miller’s first wife, Jean, died of cancer.

But tragedy and age did not dim Miller’s sardonic humor.

In Australia, he filmed mountain bikers shooting down snowy slopes with “legs of steel, nerves of ice, brains of marshmallow — and all they want from life is an unfair advantage.”

At Colorado’s Winter Park ski area, he shot dozens of rodeo cowboys awkwardly snowplowing in chaps and Stetsons. There were the feats of Zudnik, the Skiing Wonder Dog, and the venturesome Kirsten Kulver, “the human hood ornament,” who set a 1985 speed record while strapped to skis atop a race car. She went more than 153 mph.

“This kind of record-breaking takes a person with an IQ that’s unusual,” Miller said in “Beyond the Edge” (1986). “One that’s a little below room temperature.”

In the same film, he ran into Dr. Ruth Westheimer, the sex therapist, at Sun Valley.

“When I hear of somebody walking into my office being a skier, I right away have a little bit more enthusiasm talking to them,” Dr. Ruth said.

“And when I hear of someone coming onto my ski hill and talking about sex, I right away have a little more enthusiasm talking to them,” Miller told her.

Miller is survived by his wife Laurie, sons Scott and Kurt, daughter Chris and a stepson, Colin Kaufman.

Before long, professional skiers saw it as an honor to appear in a Miller film. Chris Anthony, a former Alaska extreme skiing champion, first skied for Miller during finals week at the University of Colorado.

“I was willing to drop every class and repeat the semester,” he told Salt Lake City’s Deseret News in 1998.

If Miller’s ski footage drew the experts, his cornball stories drew the fans.

He once told a reporter about hiring a photographer to shoot a skiing chimpanzee.

After four days, the photographer came back with only three shots, Miller said in disgust.

“He looked us right in the eye and said, ‘Well, the chimp was a rotten skier.’ “

Chawkins is a former Times staff writer

UPDATES:

12:40 p.m.: This article has been updated with additional details.

This article was originally published at 10:45 a.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.