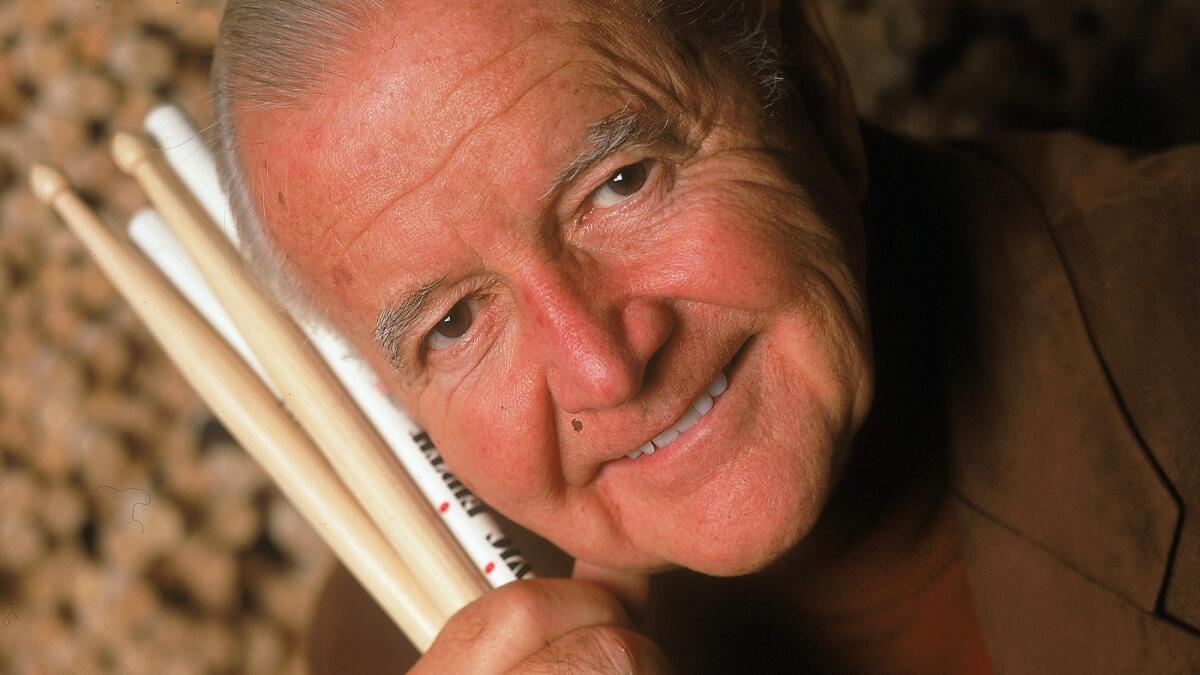

Vic Firth dies at 85; percussionist made drumsticks and mallets for legions of players

Vic Firth, a longtime timpanist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra who launched a successful drumstick company, has died at the age of 85.

When Vic Firth was growing up, he took weekly lessons on piano, trumpet, clarinet, trombone and drums —plus music theory.

Only the drums — and the drumsticks — stuck.

Firth, who for 50 years was the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s principal timpanist, also was one of the world’s largest producers of drumsticks. In a factory on the shores of Sebasticook Lake in Maine, he ran a company that turns out 12 million sticks a year — enough to stretch from Disney Hall in Los Angeles to Carnegie Hall in New York, with a side trip to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.

His sticks and mallets have been used by classical musicians around the world and by legions of jazz players and rockers, including the Rolling Stones’ Charlie Watts, Anton Fig of “The Late Show with David Letterman” and drummers for Lou Reed, Elton John, Alicia Keys, Beyonce, Jimmy Buffet and many others.

Firth died of pancreatic cancer Sunday at his Boston home, said Rob Grad, a spokesman for the Vic Firth Co. He was 85.

For more than 15 years, he also made exquisitely lathed pepper mills and other high-end culinary tools.

On celebrity chef Emeril Lagasse’s TV show in 2006, Firth played drums with drumsticks he created as Lagasse used Vic Firth pepper mills to spice up a pan full of sizzling — yes! — drumsticks.

A dapper, silver-haired man with a thick New England accent, Firth headed the percussion department at the New England Conservatory of Music for 44 years.

At the Boston Symphony, he performed with legendary musicians and conductors, including Leonard Bernstein, Serge Koussevitsky, Leopold Stokowski, Jascha Heifetz and Vladimir Horowitz. When Firth was inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame in 1997, Boston Symphony music director Seiji Ozawa described him as “quite simply, the consummate artist.”

“I believe he is the single greatest percussionist anywhere in the world,” Ozawa said. “Every performance that Vic gave was informed with incredible musicianship, elegance and impeccable timing.”

Firth started whittling his own drumsticks in the early 1960s. He later told interviewers he was frustrated by sticks that were warped, uncomfortable and improperly weighted. His conservatory students felt the same way and, in 1963, Firth started a small manufacturing operation in his basement.

It soon grew into a factory in Kingfield, Maine, that previously had manufactured sleighs. In 1994, Firth bought his 65,000-square-foot lakeside mill in Newport, Maine.

Drummers “may think twice before buying a new set of drums, but they always need sticks,” he told the Bangor Daily News in 2008. And the stick business only picked up, he said, with exuberant rock performances in which “a man in green pants and purple hair breaks it in one rim shot!”

Firth appreciated rock and once let his teenage daughters talk him into an impromptu drum solo with the Grateful Dead during a concert in Providence, R.I.

When the Boston Symphony’s manager heard about it, he sent for the errant timpanist, according to the Boston Globe.

“Tell me it isn’t true,” the manager pleaded.

It wasn’t true, Firth assured him.

But as he headed for the door, the manager asked, “Did you really do it?”

“And I said, ‘Of course I did,’” Firth told the Globe.

“‘Just don’t do it again,’ he said, and I didn’t.”

Born in Winchester, Mass., on June 2, 1930, Everett Joseph Firth grew up in Sanford, Maine. His father, Everettt E. Firth, a professional trumpet and cornet player, hoped his son would become a music arranger in Hollywood.

By the time he was 16, Vic had formed an 18-piece big band. When he was 21 and still a conservatory student, he was exasperated at the length of time Boston Symphony music director Charles Munch was taking to fill a rare percussion vacancy.

“I told him how grateful I was for his interest and support, but I needed a decision because I had another job offer — which wasn’t true,” Firth said. “Youth has more nerve than brains.”

He got the job. At the time, the orchestra’s average age was about 55.

Firth retired in 2002.

“He is still playing magnificently,” the Boston Globe said, “but he says he would rather leave two or three years too early than a single minute too late.”

In his later years, he focused on the elaborate processes and custom equipment his factory developed for some 200 varieties of drumsticks and mallets, as well as wooden culinary gizmos. In 2010, his company merged with the Avedis Zildjian Co., a manufacturer of cymbals, and soon sold off the pepper-mill end of the business.

Firth is survived by his wife, Olga; daughters Tracy Frith and Kelly DeChristopher; and sister Sherrill Auld.

Twitter: @schawkins

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.