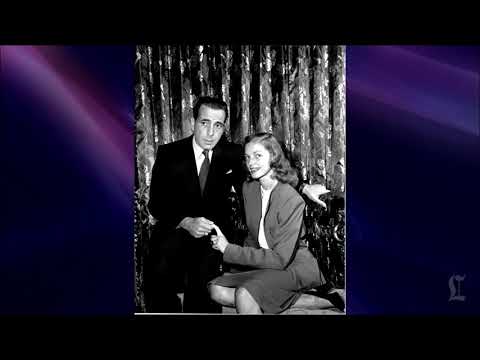

Lauren Bacall, who taught Humphrey Bogart how to whistle, dies at 89

Sultry Hollywood screen and stage legend Lauren Bacall has died at the age of 89.

At 19, Lauren Bacall was living every red-blooded American woman’s dream: Humphrey Bogart was standing inches from her, waiting for her to speak.

They were shooting a crucial scene in director Howard Hawks’ 1944 wartime drama “To Have and Have Not,” but her head was shaking, as was her hand and the cigarette she was holding. And trembling was not in the script.

So Bacall tipped her head down so that her chin almost touched her chest. It was the only way she could steady herself. From that stance she gazed upward at Bogart.

In that moment “the look” was born — the one that would make the sultry-voiced actress a screen legend and redefine sexuality for generations to follow.

Bacall, the Hollywood icon who taught Bogart how to whistle in the film that launched her career and turned “Bogie and Bacall” into one of the movie world’s most celebrated couples, died Tuesday in New York, where she had lived for several decades. She was 89.

Her death was confirmed by Robbert de Klerk, co-managing partner of the Humphrey Bogart Estate with her son, Stephen Bogart. The cause of death was not disclosed.

In a statement released on social media, the Bogart Estate expressed deep sorrow and “great gratitude for her amazing life.” Her daughter, Leslie Bogart, said the family was not releasing any other details at this time.

Few Hollywood careers began as memorably as that of Bacall, who won two Tony Awards on Broadway over an acting career that spanned more than 60 years.

She was a fledgling New York stage actress and a model whose pictures in Harper’s Bazaar came to the attention of Hawks, who placed her under personal contract and cast her opposite Bogart, who at 44 was more than twice her age when they met on screen.

“Anybody got a match?” Bacall, appearing in the open doorway of charter boat captain Bogart’s Martinique hotel room, asks in the famous scene. He tosses a small box of matches to the tall, slim young stranger in a tailored suit with padded shoulders. She takes out a match, strikes it and gazes indifferently at Bogart before lighting her cigarette.

“Thanks,” she says, tossing the matchbox to him and leaving.

But as much a Bacall trademark as the look she gave him was her voice, kept at a low register at Hawks’ direction throughout the film. It gave the young actress a seductive worldliness that was never so evident as when she delivered one of the most famous lines in movie history to Bogart.

“You know you don’t have to act with me, Steve,” she says to him. “You don’t have to say anything and you don’t have to do anything — not a thing. Oh, maybe just whistle.

“You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and blow.”

Hawks later said he told Bogart that he considered him “the most insolent man on the screen, and I’m going to try to make the girl just as insolent as you.”

Warner Bros. trumpeted its “provocative” new discovery in the movie’s trailer as “The only kind of woman for his kind of man!”

Critic James Agee wrote at the time that Bacall was “the toughest girl a piously regenerate Hollywood has dreamed of in a long, long while.”

The on-screen chemistry between the two co-stars was an extension of what was happening off-screen. During the film’s production, Bacall and the twice-divorced, unhappily married Bogart began an affair.

They were married in 1945 and teamed up in three more Warner Bros. movies over the next few years: “The Big Sleep,” “Dark Passage” and “Key Largo.”

“To Have and Have Not” showcased Bacall in “a perfect role that set her persona for life,” said Jeanine Basinger, author of “A Woman’s View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women” and the head of the film studies program at Wesleyan University.

“So she was a legend from the very first minute,” Basinger told The Times in 2004. “And she was so unique — her looks, her style, her voice.”

Although Bacall was dismissed by some critics early on, Basinger said, the longevity and quality of her career proved that she “wasn’t just an appendage to Humphrey Bogart.”

In the years after their marriage, Bacall starred in films such as “Young Man with a Horn” with Kirk Douglas, “Bright Leaf” with Gary Cooper, “How to Marry a Millionaire” with Betty Grable and Marilyn Monroe, “Blood Alley” with John Wayne, “Written on the Wind” with Rock Hudson and “Designing Woman” with Gregory Peck.

But Bacall put her marriage before her career.

“I was so blinded by Bogie I couldn’t think of anything else,” she told the Associated Press in 1999. “All I thought of was being with him. He didn’t ask me not to be an actress. But he said he had been married to three actresses and their careers always came first. If I wanted a career that badly, OK, he would help me as much as he could, but he wouldn’t marry me.

“I had to promise to put our life together first. That’s what I did.”

Their marriage ended in 1957 when Bogart died of cancer at the age of 57.

A brief engagement to Frank Sinatra followed, as did a rocky, eight-year marriage to actor Jason Robards.

A full list of immediate survivors was not available, but they include her two children with Bogart, Stephen and Leslie, and her son with Robards, Sam.

In the years after Bogart’s death, Bacall’s film career waned. But she appeared on Broadway in the 1959-60 comedy “Goodbye Charlie,” the 1965-68 comedy “Cactus Flower” and the 1970-72 musical “Applause,” which earned Bacall her first Tony Award.

Of her performance, critic Walter Kerr raved: “Miss Bacall, with this thundering appearance, ceases being a former movie star and becomes a star on the stage, thank you.”

Her return to Broadway in 1981 to star in “Woman of the Year,” a hit musical adaptation of the old Spencer Tracy-Katharine Hepburn movie, brought Bacall her second Tony Award.

In 1999, she again starred on Broadway in the Noel Coward play “Waiting in the Wings.”

By then, she also had appeared in films such as “Harper” with Paul Newman, “The Shootist” with John Wayne, “Murder on the Orient Express” with an all-star cast and “The Fan” with James Garner.

“The Mirror Has Two Faces,” a 1996 romantic comedy, brought Bacall her only Academy Award nomination, as supporting actress, for playing what Times movie critic Kenneth Turan described as Barbra Streisand’s “madcap meddling mother.”

She appeared opposite Nicole Kidman in the 2004 mystery “Birth.” A few years later she played herself in an episode of “The Sopranos”.

She received an honorary Oscar in 2009.

But no matter what she did personally or professionally, people never stopped identifying Bacall with Bogart, who became a major cinematic cult figure in the 1960s.

“I’ll never get away from him,” Bacall told Newsday in 1999. “I accept that. He was the emotional love of my life, but I think I’ve accomplished quite a bit on my own.”

She was born Betty Joan Perske on Sept. 16, 1924, in New York City. Her mother left her father when Bacall, an only child, was 6, and she was raised by her mother, a corporate executive secretary.

After her parents’ divorce, her mother, a Romanian emigre, took the name “Bacal,” half of her maiden name Weinstein-Bacal, for herself and her daughter. (While attempting to break into acting in New York as a teenager, Bacall added the extra “l” to keep people from rhyming Bacal with “crackle.”)

With an uncle helping pay for her support, Bacall attended a boarding school for girls in Tarrytown, N.Y. She studied ballet and after returning to Manhattan for high school — she graduated at 15 — she took Saturday morning acting classes for four years at the New York School of the Theatre.

Although she used to cut school as a teenager to see Bette Davis films, Bacall dreamed of becoming a Broadway actress, and she studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where she met and went out with an older student, Kirk Douglas.

Unable to afford a second year at the Academy, Bacall worked as a theater usher and began modeling while making the rounds for acting jobs.

Bacall’s work as a model brought her to the attention of Harper’s Bazaar fashion editor Diana Vreeland, which led to the magazine photos that brought her to the attention of director Hawks.

Although Hawks renamed her Lauren for the screen, friends called her Betty.

A lifelong Democrat who knew Harry Truman and Adlai Stevenson and considered President Franklin Roosevelt “my god” — “I just worshipped him” — Bacall had a longtime interest in politics.

While promoting “To Have and Have Not,” she famously sat on top of an upright piano played by then-Vice President Truman at a National Press Club luncheon in Washington; the photo ran on front pages around the world.

In 1947, in response to the House Un-American Activities Committee’s investigations into claims of communist influences in Hollywood, Bogart and Bacall joined other Hollywood stars, directors and writers in forming the Committee for the First Amendment.

Members drew up a formal petition protesting the House committee’s attempt to “smear the motion picture industry,” saying, in part, that “any investigation into the political beliefs of the individual is contrary to the basic principles of our democracy.”

Bogart and Bacall also were among a group of Hollywood celebrities who flew to Washington, D.C., to attend the hearings, meet with senators and representatives, hold press conferences and present their petition at the Capitol.

Bogart and Bacall’s son Stephen was born in 1949 and daughter Leslie was born in 1952, the year the family moved into a house in Holmby Hills.

The Bogarts’ home became the site of frequent gatherings of their show-business friends. Bacall was voted “den mother” of what became known as the Holmby Hills Rat Pack.

“In order to qualify” for membership, Bacall wrote in her autobiography “By Myself,” “one had to be addicted to nonconformity, staying up late, drinking, laughing and not caring what anyone thought or said about us.”

The good times came to an end Jan. 14, 1957, when Bogart died. She moved to New York in 1961 to “get out from under being ‘Bogart’s widow,’ ” she later wrote, but her legacy remained intertwined with his.

“Young people, even in Hollywood, ask me, ‘Were you really married to Humphrey Bogart?’ ” she said in a cantankerous interview for Vanity Fair four years ago, shortly after breaking her hip. “ ‘Well, yes, I think I was,’ I reply. You realize yourself when you start reflecting — because I don’t live in the past, although your past is so much a part of what you are — that you can’t ignore it. But I don’t look at scrapbooks. I could show you some, but I’d have to climb ladders, and I can’t climb.”

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

Times staff writers Elaine Woo and Ryan Parker contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.