Joe Hicks dies at 75; prominent black conservative

Joe Hicks, a Los Angeles-based community activist whose views as a black conservative were solicited often by the media, died Sunday at Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica following complications after a routine hernia operation. He was 75.

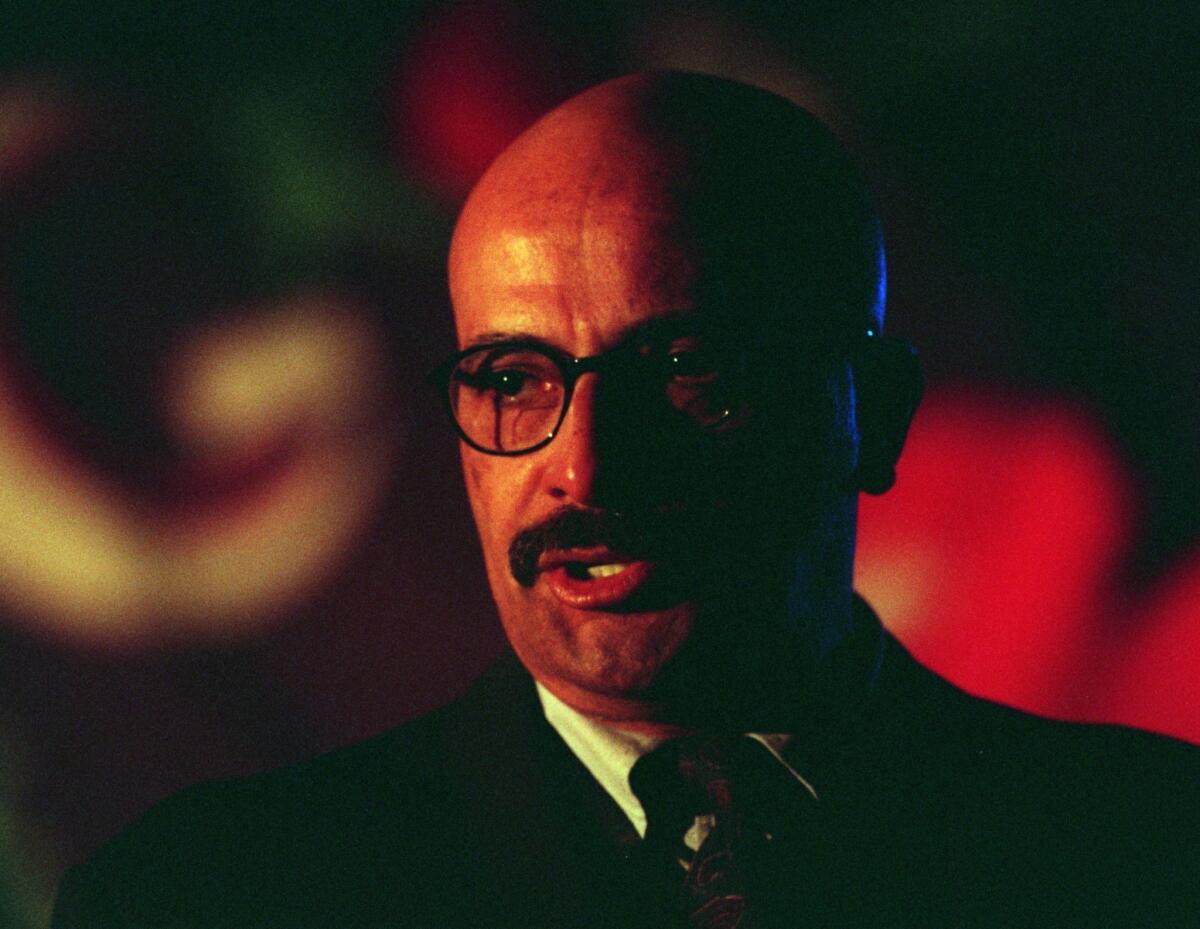

In recent years Hicks — with his bald head and thick mustache — had become a familiar right-wing pundit in debates over the high-profile shooting deaths of black people at the hands of police officers. He cautioned against racial distrust, argued there were legitimate reasons why black communities draw police attention and was ambivalent about the Black Lives Matter movement.

“He would take a stand on an issue because he thought it was right, whether it was popular or not,” said David Lehrer, who co-founded with Hicks the local race relations think tank Community Advocates. “He had a very strong moral compass. He was firm and strong and principled and warm.”

In a letter published in the Los Angeles Times shortly after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the death of Trayvon Martin, Hicks and Lehrer contended there was “no wave of bigotry directed at blacks. All this talk is demagogic posturing, and it’s dangerous. … The biggest threat to the lives of young blacks is other young blacks, not white bigots.”

Hicks’ path as an activist was curious.

He began as a militant radical in the Black Power movement and became a card-carrying Communist in the 1970s. Then, two decades later, Hicks found his niche as a conservative.

Recently, though, he quit the Republican Party because of his disgust with Donald Trump.

The youngest of three children, Hicks was born into an impoverished South Los Angeles family. His mother stayed at home while his father picked up odd jobs, at one point laboring on a farm.

After graduating from Jefferson High School, where he was a highly regarded sprinter, Hicks took courses at Cal State Los Angeles with notions of becoming an architectural draftsman. He found himself dissuaded by the lack of black professionals in the field. Instead, he joined the Navy, spending time in Japan.

By the time the Watts riots broke out, Hicks had returned to Los Angeles. Sitting on his front porch, he was outraged to see military personnel coming down the street, their guns aimed at him.

“That was his complete radicalization moment,” recalled his former wife, Elizabeth Hicks. “Before that he was mildly interested in history and politics, but that was the point where he went, ‘This is not OK.’”

The two met while working in support of affirmative action on college campuses. Years later, one of their daughters would climb onto the lap of visiting South African leader Nelson Mandela — an exciting moment for the couple who had been involved in the anti-apartheid movement. At the time, Hicks subscribed to a black nationalist viewpoint and considered himself extremely liberal.

An auto enthusiast, Hicks found work writing for car magazines, but eventually took a job as the communications director of the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

In the early 1990s, he became executive director of the greater Los Angeles chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the civil rights group once presided over by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Hicks also co-chaired the Black-Korean Alliance, an organization dedicated to promoting harmony between the communities, and was a regular co-host of KCET’s public affairs program “Life & Times.”

From 1997 to 2001, he served as the executive director of the L.A. City Human Relations Commission under Mayor Richard Riordan.

Around that time, Hicks began re-examining his politics. Elizabeth Hicks believes Sept. 11 contributed to his disenchantment.

“It really made him and myself re-evaluate our stances,” she said. “It was the feeling of being attacked as a nation. We were hypercritical before and we learned to realize the freedoms we have here are important and need to be valued. I stayed liberal and he went the other direction.”

Friends say the change was also influenced by Hicks’ travels as an advocate of affirmative action. He took on ex-Klansman David Duke in a much publicized debate at Cal State Northridge that ended with protestors nearly inciting a riot.

But continuous research on the policy eventually led Hicks to believe it wasn’t in the best interest of students of color.

“A pillar of what he had believed for years kind of crumbled,” Lehrer said.

Hicks became a staunch critic of affirmative action and gained a reputation for his unapologetic but thoughtful approach on heated issues of race, appearing on scores of local and national television and radio shows, and publishing myriad opinion pieces. For three years, he hosted the weekly “Joe Hicks Show” on KFI-AM.

Hicks took care to set aside his role as commentator whenever possible and reveled in attending his children’s basketball games and swimming and track meets, family members said.

He is survived by his four daughters, Tamani Hicks-Littleton, Hasani Hicks-McGriff, Katarina Hicks and Natasha Hicks; his son, Jabali Hicks; and his sister Annie Hicks-Roberts.

A memorial is scheduled for 11 a.m. on Sept. 17 at the Los Angeles Central Library.

Twitter: @corinaknoll

ALSO

Max Ritvo, L.A. poet who chronicled his cancer battle, dies at 25

‘No, that can’t be true’: Angelenos react to the death of Mexican crooner Juan Gabriel

Gene Wilder dies at 83; ‘Willy Wonka’ star and Mel Brooks collaborator

UPDATES:

6:25 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details.

This article was originally published at 4 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.