Huell Howser dies at 67; TV host profiled California people and places

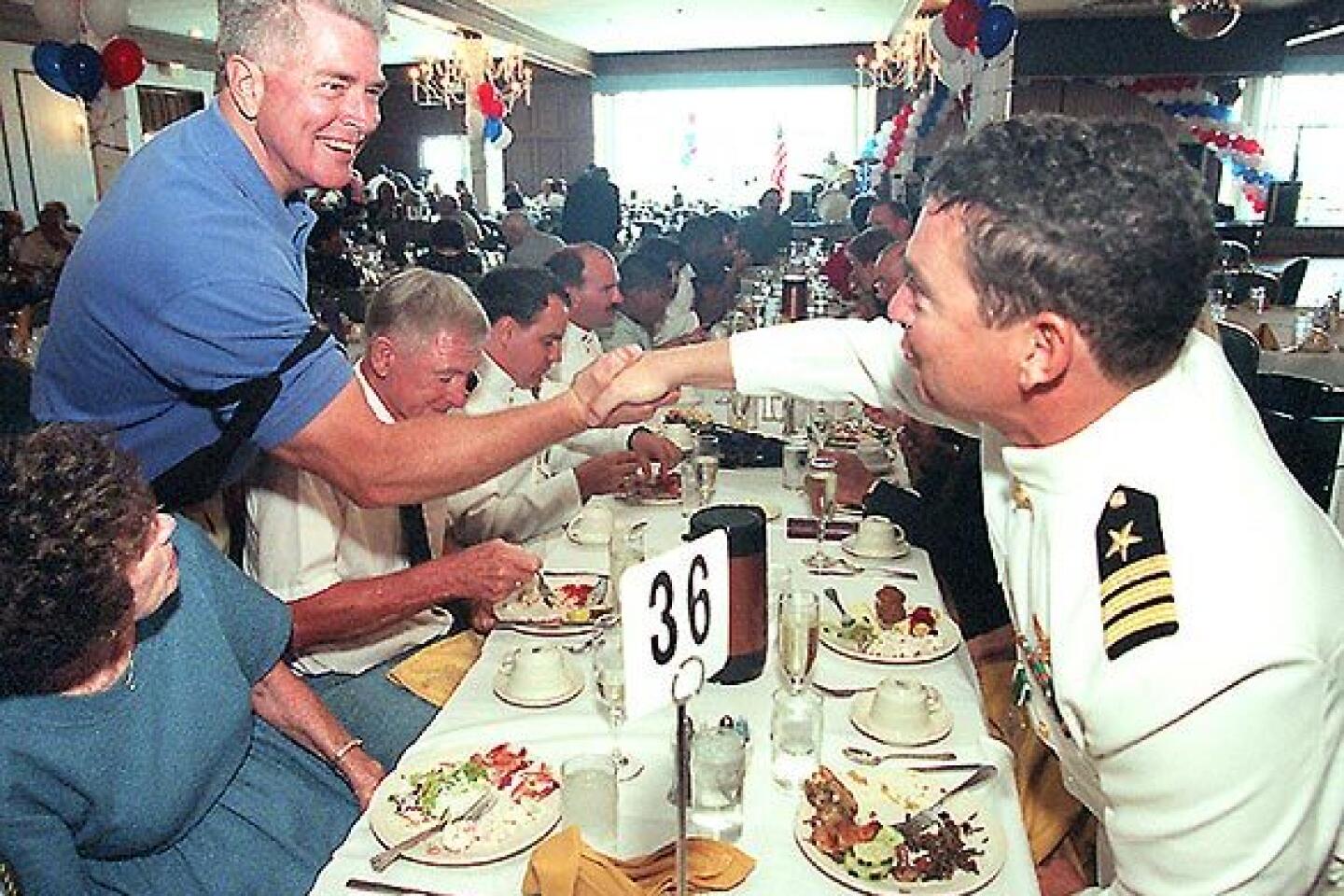

Huell Howser seemed an unlikely candidate to become a television star — a big, grinning ex-Marine with a molasses-smooth Tennessee drawl and an eye for stories that others would pass by, such as the Bunny Museum in Pasadena and the rendering of artwork out of dryer lint.

His platform was traditional and unflashy — highlighting familiar and obscure spots all around California in public television series, particularly “California’s Gold.” But though his shows were focused on points and people of interest, it was Howser who turned into the main attraction, tackling his subjects with an awe-struck curiosity and relentless enthusiasm.

Howser, 67, an iconic figure in public television, died at home Sunday night, his assistant Ryan Morris said. The cause of death was not released.

FOR THE RECORD:

Huell Howser: The obituary of public television host Huell Howser in the Jan. 8 Section A said that, according to his assistant, he had died the night of Jan. 6. However, his death certificate lists his death, from prostate cancer, as occurring at 2:35 a.m. Jan. 7. —

“He was a wonderful man with real generosity — he kept alive a sense of the drama, beauty and poetry of California,” said Kevin Starr, a USC history professor who formerly served as California’s state librarian. “His sense of the state was incredible, positioning it as a place for everybody. Not just the elite, but for ranchers, farmers, workers. He showed truck-stop restaurants. Huell had an extraordinarily inclusive, democratic view of all things California. He emphasized the eccentricities, but never sacrificed showing the ordinary, simple side.”

A former local television news reporter, Howser struck out on his own in the 1980s — producing “Videolog,” a series of human interest stories, for public television station KCET-TV. In 1990, he launched his “California’s Gold” series that aired on public TV stations throughout the state.

Howser’s primary success could be attributed to his persona of an amiable and relentlessly curious seeker of all things California, large and small, the flashy, the off-the-wall and the off-the-beaten-track. His upbeat boosterism accompanied an appearance that was simultaneously off-kilter and yet somehow cool with a hint of retro — a square thatch of hair, sunglasses, shirts that showed off a drill sergeant’s build and bulging biceps, and expressions that ranged from pleasantness to jaw-dropping wonder with some of his discoveries.

Topping it all off was an irresistibly folksy manner, with frequent exclamations of “Oh my gosh!” and “Isn’t that amazing?” The voice and the aw-shucks demeanor were also catnip for comedians who delighted in imitating his tone. He was once parodied on “The Simpsons,” and he was a favorite target of comedian Adam Carolla on his radio shows and podcasts. But he also proved to be a savvy businessman through his deals with broadcasters and sales of his shows on DVDs.

“Every night on KCET, Huell introduced us to people we would not have otherwise met, and took us to places we would not have otherwise have traveled,” Al Jerome, president and chief executive of KCET, said in a statement. “Huell elevated the simple joys and undiscovered nuggets of living in our great state. He made the magnificence and power of nature seem accessible by bringing it into our living rooms.”

Howser’s death came only weeks after the announcement Nov. 27 that he was retiring and not filming any more original episodes of “California’s Gold.”

Despite shifts in TV trends and fashions, Howser’s approach never varied — he was merely a man with a microphone and a camera. He played down its simplicity (“It’s pretty basic stuff … it’s not brain surgery”) and said it fit his strategy: to shine a spotlight on the familiar and the obscure places and people all over California.

“We have two agendas,” Howser said in a 2009 interview with The Times. “One is to specifically show someone China Camp State Park or to talk to the guys who paint the Golden Gate Bridge. But the broader purpose is to open up the door for people to have their own adventures. Let’s explore our neighborhood; let’s look in our own backyard.”

His anti-glitz, aggressively genial approach with people was his trademark. He expressed endless amazement at his subjects, whether it was the making of French dip sandwiches at Philippe’s restaurant in downtown Los Angeles, the burgers at the Apple Pan (“This is like … amazing!”) or the massive swarm of flies buzzing around Mono Lake. “Look at this, look at this,” he would often exclaim, prodding his interviewees to always tell him more.

Some of the people he interviewed had thought it was a put-on, but they came to find that Howser was the genuine article.

“I had watched him while growing up, and I always thought that aw-shucks stuff was just an act,” said Paul Chavez, chairman of the board of directors of the Cesar Chavez Foundation in the Tehachapi Mountains, which Howser profiled two years ago.

“But after a few minutes, Huell was like an old friend that I had known for years,” said Chavez, son of the late labor leader. “His enthusiasm was contagious. Shortly after the show ran, we got a noticeable increase in visitors.”

Real estate executive Kimberly Lucero echoed Chavez’s assessment about Howser’s enthusiasm. Lucero was the host’s guide in 2005 for a show on downtown Los Angeles’ historic Eastern Columbia Building.

Howser was almost breathless during the taping, Lucero said. As he surveyed the gold-leaf entrance, she recalled, Howser exclaimed: “Look at this — what in the world were they thinking when they built things like this?”

“His excitement was truly infectious,” Lucero said. “Nothing was staged.”

But even those who poked fun at his upbeat attitude were seldom mean-spirited or cruel — their affection for him was evident through the wisecracks.

“He had this Gomer Pyle thing going, which is hard to do,” said Carolla, the comedian who enjoyed mocking Howser. “He would talk to people, just an ordinary person, and seemed genuinely interested and surprised at anything they said, treating them like they were amazing. He was such a kind soul. The world could use a few more Huell Howsers.”

He was such a local fixture that a Pink’s hot dog was named after him. Although those who came into contact with him said he was the same off-camera as he was on, he maintained a sense of mystery.

Never married, Howser was intensely private, rarely giving glimpses into his own life. He had an apartment on Rossmore Boulevard in Los Angeles, but he also lived in his “dream house” in Twentynine Palms, which he decorated with midcentury furniture he bought from secondhand stores in Palm Springs.

Howser was aware that his ever-present cheerfulness was an eyebrow-raiser.

“Sometimes, people say, ‘Are you putting that on?’” he said in 2009. “That’s kind of a sad commentary, don’t you think? Like there’s got to be something wrong with someone who’s enthusiastic and happy like that. Do I have bad days? Yes. Do I get depressed? Yes. Am I concerned about the state of the California economy and budget? I’m not some Pollyanna who doesn’t recognize that there’s hunger and poverty and racism in the world.”

Howser was born Oct. 18, 1945, in Gallatin, Tenn., near Nashville. His father, Harold, was a lawyer, and his mother, Jewel, was a homemaker. “Huell” is a combination of both their names.

In 2011, Howser announced that he was donating all episodes of his series to Chapman University, a private college in Orange, to be digitized and made available for a worldwide online audience.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.